1934: Tenebrae in Slovakia, Easter in Hungary

An Englishman witnesses the vigorous popular liturgical life of interwar central Europe

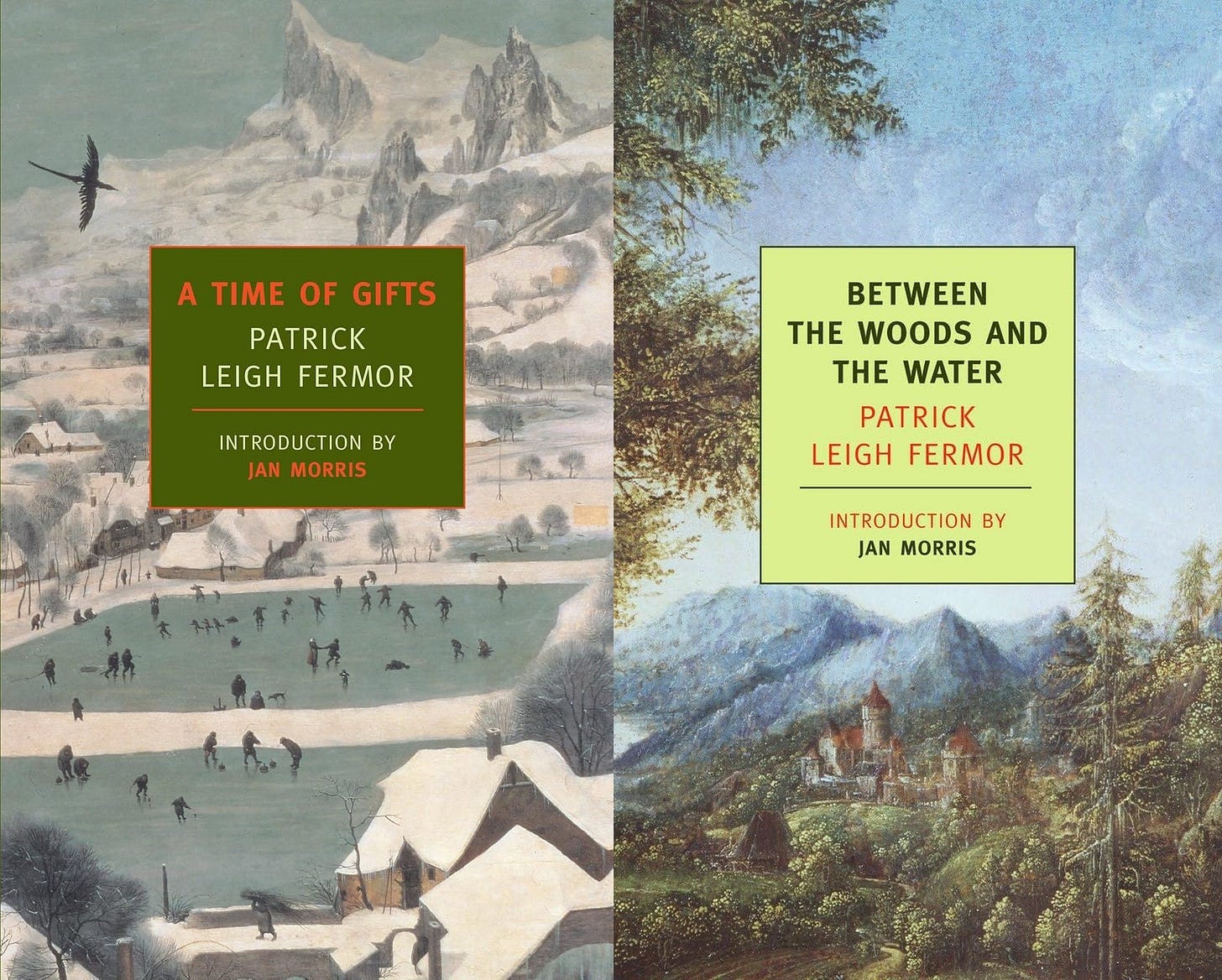

One of the finest English stylists of the last century, and certainly one of the most dashing heroes of World War II, was the adventuresome and long-lived Patrick Leigh Fermor (1915–2011). Well before his association with the military, he decided in 1933, as an eighteen-year-old dropout, to walk across Europe, starting in Holland and ending in Istanbul. The three books he wrote decades later about the experience, drawing from diaries and notes made at the time, make for extraordinary reading: A Time of Gifts (1977), Between the Woods and the Water (1986), and the posthumously released The Broken Road (2013). Here is not the place to say why I love them so much, but perhaps when you’ve read or listened to me reading the following accounts of the Tenebrae in Slovakia and the Easter vigil in Hungary that Leigh Fermor witnessed in 1934—taken from the end of the first volume and the start of the second—you’ll quickly discover why I find him so delightful.

A Time of Gifts (pp. 296–98)

The dry paths had turned my boots and puttees white with dust. The empty sky was the clear blue of a bird’s egg and I was walking in my shirt sleeves for the first time. Slower and slower however: a nail in one of my boots had mutinied. I limped into the thatched and white-washed village of Köbölkut as it was getting dark. There was a crowd of villagers in the street and I drifted into the church with them and wedged myself into the standing congregation.

The women all had kerchiefs tied under the chin. The men, shod in knee-boots, or in raw-hide moccasins cross-gartered halfway up their shanks, had wide felt hats in their hands, or cones of fleece. Over the shoulders of a couple of shepherds were flung heavy white capes of stiff homespun frieze. In spite of the heat and the crush, one of them was wrapped in a cloak of matted and uncured sheepskin, shaggy-side out, that reached down to the flagstones. Things had become much wilder in the last hundred miles. The faces had a knobbly, untamed look: they were peasants and countrymen to the backbone.

The candles, spiked on a triangular grid, lit up these rustic masks and populated the nave behind them with a crowd of shadows. At a pause in the plainsong one of the tapers was put out. I realized, all at once, that it was Maundy Thursday. Tenebrae were being sung, and very well. The verses of the penitential psalms were answering each other across the choir and the slow recapitulations and rephrasings of the responsories were unfolding the story of the Betrayal. So compelling was the atmosphere that the grim events might have been taking place that night. The sung words crept step by step through the phases of the drama. Every so often, another candle was lifted from its pricket on the triangle and blown out. It was pitch dark out of doors and with the extinction of each flame the interior shadows came closer. It heightened the chiaroscuro of these rough country faces and stressed the rapt gleam in innumerable eyes; and the church, as it grew hotter, was filled by the smell of melting wax and sheepskin and curds and sweat and massed breath. There was a ghost of old incense in the background and a reek of singeing as the wicks, snuffed one after the other, expired in ascending skeins of smoke. “Seniores populi consilium fecerunt,” the voices sang, “ut Jesum dolo tenerent et occiderent”; and a vision sprang up of evil and leering elders whispering in a corner through toothless gums and with beards wagging as they plotted treachery and murder. “Cum gladiis et fustibus exierunt tamquam ad latronem...” Something in the half-lit faces and the flickering eyes gave a sinister immediacy to the words. They conjured up hot dark shadows under a town wall and the hoarse shouts of a lynch-mob; there was a flicker of lanterns, oafish stumbling in the steep olive groves and wild and wheeling shadows of torches through tree trunks: a scuffle, words, blows, a flash, lights dropped and trampled, a garment snatched, someone running off under the branches. For a moment, we—the congregation—became the roughs with the blades and the cudgels. Fast and ugly deeds were following each other in the ambiguity of the timbered slope. It was a split-second intimation! By the time the last of the candles was borne away, it was so dark that hardly a feature could be singled out. The feeling of shifted rôles had evaporated; and we poured out into the dust. Lights began to kindle in the windows of the village and a hint of moonrise shone at the other end of the plain.

Between the Woods and the Water (pp. 9–14)

Perhaps I had made too long a halt on the bridge. The shadows were assembling over the Slovak and Hungarian shores and the Danube, running fast and pale between them, washed the quays of the old town of Esztergom, where a steep hill lifted the basilica into the dusk. Resting on its ring of columns, the great dome and the two Palladian belfries, tolling now with a shorter clang, surveyed the darkening scene for many leagues. All at once the quay and the steep road past the Archbishop’s palace were deserted. The frontier post was at the end of the bridge, so I hastened into Hungary: the people that Easter Saturday had gathered at the river’s side had climbed to the Cathedral square, where I found them strolling under the trees, conversing in expectant groups. The roofs fell away underneath, then forest and river and fen ran dimly to the last of the sunset.

A friend had written to the Mayor of Esztergom: ‘Please be kind to this young man who is going to Constantinople on foot.’ Planning to look him up next day, I asked someone about the Mayor’s office and before I knew what was happening, and to my confusion, he had led me up to the man himself. He was surrounded by the wonderfully-clad grandees I had been admiring beside the Danube. I tried to explain that I was the tramp he had been warned about and he was politely puzzled; then illumination came, and after a quick and obviously comic conversation with one of the magnificent figures, he committed me to his care and hastened across the square to more serious duties. The charge was accepted with an amused expression; my mentor must have been saddled with me because of his excellent English. His gala costume was dark and splendid; he carried his scimitar slung nonchalantly in the crook of his arm and a rimless monocle flashed in his left eye.

At this very moment, all eyes turned downhill. The clatter of hoofs and a jingle of harness had summoned the Mayor to the Cathedral steps, where a scarlet carpet had been laid. Clergy and candle-bearers were ceremoniously gathered and when the carriage halted a flame-coloured figure uncoiled from within and the Cardinal, Monsignor Serédy, who was also Archbishop of Esztergom and Prince-Primate of Hungary, slowly alighted and offered his ringed hand to the assembly and everyone in turn fell on one knee. His retinue followed him into the great building, then a beadle led the Mayor’s party to the front pews which were draped in scarlet. I made as though to slink to a humbler place, but my mentor was firm: “You’ll see much better here.”

Holy Saturday had filled half the vast cathedral and I could pick out many of the figures who had been on display by the river: the burghers in their best clothes, the booted and black-clad peasants, the intricately-coifed girls in their coloured skirts and their white pleated sleeves panelled with embroidery, the same ones who had been hastening over the bridge with nosegays of lilies and narcissi and kingcups. There were black and white Dominicans, several nuns and a sprinkling of uniforms, and near the great doors a flock of Gypsies in clashing hues leaned whispering and akimbo. It would scarcely have been a surprise to see one of their bears amble in and dip its paw in a baroque holy-water stoup shaped like a giant murex and genuflect.

How unlike the ghostly mood of Tenebrae two nights before! As each taper was plucked from its spike the shadows had advanced a pace until darkness subdued the little Slovak church. Here, light filled the great building, new constellations of wicks floated in all the chapels, the Paschal Candle was alight in the choir and unwinking stars tipped the candles that stood as tall as lances along the high altar. Except for the red front pews, the Cathedral, the clergy, the celebrating priest and his deacons and all their myrmidons were in white. The Archbishop, white and gold now and utterly transformed from his scarlet manifestation as Cardinal, was enthroned under an emblazoned canopy and the members of his little court were perched in tiers up the steps. The one on the lowest was guardian of the heavy crosier and behind him another stood ready to lift the tall white mitre and replace it when the ritual prompted, arranging the lappets each time on the pallium-decked shoulders. In the front of the aisle, meanwhile, the quasi-martial bravery of the serried magnates—the coloured doublets of silk and brocade and fur, the gold and silver chains, the Hessian boots of blue and crimson and turquoise, the gilt spurs, the kalpaks of bearskin with their diamond clasps, and the high plumes of egrets’ and eagles’ and cranes’ feathers—accorded with the ecclesiastical splendour as aptly as the accoutrements in the Burial of Count Orgaz: and it was the black attire—like my new friend’s, and the armour of the painted knights in Toledo—that was the most impressive. Those scimitars leaning in the pews, with their gilt and ivory cross-hilts and stagily gemmed scabbards—surely they were heirlooms from the Turkish wars? When their owners rose jingling for the Creed, one of the swords fell on the marble with a clatter. In old battles across the puszta, blades like these sent the Turks’ heads spinning at full gallop; the Hungarians’ heads too, of course...

Soon, after an interval of silence, sheaves of organ-pipes were thundering and fluting their message of risen Divinity. Scores of voices soared from the choir, Alleluiahs were on the wing, the cumulus of incense billowing round the carved acanthus leaves was winding aloft and losing itself in the shadows of the dome and new motions were afoot. Led by a cross, a vanguard of clergy and acolytes bristling with candles was already half-way down the aisle. Next came a canopy with the Sacrament borne in a monstrance; then the Archbishop; the Mayor; the white-bearded and eldest of the magnates, limping and leaning heavily on a malacca cane; then the rest. Urged by a friendly prod, I joined the slow slipstream and soon, as though smoke and sound had wafted us through the doors, we were all outside.

As the enormous moon was only one night after the full, it was almost as bright as day. The procession was down the steps and slowly setting off; but when the waiting band moved in behind us and struck up the opening bars of a slow march, the notes were instantaneously drowned. Wheels creaked overhead, timbers groaned and a many-tongued and nearly delirious clangour of bells came tumbling into the night; and then, between these bronze impacts, another sound, like insistent clapping, made us all look up. An hour or so before, two storks, tired by their journey from Africa, had alighted on a dishevelled nest under one of the belfries and everyone had watched them settle in. Now, alarmed by the din, desperately flapping their wings and with necks outstretched, they were taking off again, scarlet legs trailing. Black feathers opened along the fringes of their enormous white pinions and then steady and unhastening wing-beats lifted them beyond the chestnut leaves and into the sky as we gazed after them. “A fine night they chose for moving in,” my neighbour said, as we fell in step.

Not a light showed in the town except for the flames of thousands of candles stuck along the window-sills and twinkling in the hands of the waiting throng. The men were bareheaded, the women in kerchiefs, and the glow from their cupped palms reversed the daytime chiaroscuro, rimming the lines of jaw and nostril, scooping lit crescents under their brows and leaving everything beyond these bright masks drowned in shadow. Silently forested with flames, street followed street and as the front of the procession drew level everyone kneeled, only to rise to their feet again a few seconds after it had moved on. Then we were among glimmering ranks of poplars and every now and then the solemn music broke off. When the chanting paused, the ring of the censer-chains and the sound of the butt of the Archbishop’s pastoral staff on the cobbles were joined by the croaking of millions of frogs. Woken by the bells and the music, the storks in the town were floating and crossing overhead and looking down on our little string of lights as it turned uphill into the basilica again. The intensity of the moment, the singing and candle flames and incense, the feeling of spring, the circling birds, the smell of fields, the bells, the chorus from the rushes, thin shadows and the unreality of the moon over the woods and the silver flood—all these things hallowed the night with a spell of great beneficence and power.

When it was all over, everyone emerged once more on the Cathedral steps. The carriage was waiting; and the Archbishop, back in cardinal’s robes and the wide ermine mantle that showed he was a temporal as well as an ecclesiastical Prince, climbed slowly in. His gentleman-at-arms, helped by a chaplain with a prominent Adam’s apple and pincenez and a postillion in hussar’s uniform, were gathering in his train, yard upon yard, like fishermen with a net, until it filled the carriage with geranium-coloured watered-silk. The chaplain climbed in and sat opposite, then the gentleman-at-arms, sitting upright with black-gloved hands on the hilt of his scimitar. The postillion folded the steps, a small busbied tiger slammed a door painted with arms under a tasselled hat and when both of them had leapt up behind, the similarly fur-hatted coachman gave a twitch to the reins, the ostrich feathers nodded and the four greys moved off. As the equipage swayed down the hill, applause rippled through the gathered crowd, all hats came off and a hand at the window, pastorally ringed over its red glove, fluttered in blessing.

On the moonlit steps everyone was embracing, exchanging Easter greetings and kissing hands and cheeks. The men put on their fur hats and readjusted the slant of their dolmans and, after the hours of Latin, Magyar was bursting out in a cheerful dactylic rush.

“Let’s see how those birds are getting on,” my mentor said, polishing his monocle with a silk bandana. He sauntered to the edge of the steps, leant on his sword as though it were a shooting-stick and peered up into the night. The two beaks were sticking out of the twigs side by side and we could just make out the re-settled birds fast asleep in the shadows. “Good!” he said. “They’re having a nice snooze.”

We rejoined the others and he offered his cigarette case round, chose one himself with care and tapped it on the gnarled gold. Three plumes tilted round his lighter flame in a brief pyramid and fell apart. He drew in a deep breath, held it for a few seconds and then, with a long sigh, let the smoke escape slowly in the moonlight. “I’ve been looking forward to that,” he said. “It’s my first since Shrove Tuesday.”

The evening ended in a dinner party at the Mayor’s with barack to begin with and floods of wine all through, and then Tokay, and in the end a haze surrounded those gorgeously-clad figures. Afterwards the Mayor apologetically told me that as the house was crowded out, a room had been found for me at a neighbour’s. No question of my stumping up! Next morning, soberly dressed in tweed and a polo-necked jersey, my stork-loving friend picked me up in a fierce Bugatti and only the scimitar among his bags on the back seat hinted at last night’s splendours. We went to see the pictures in the Archbishop’s palace; then he said, why not come in his car? We would be in Budapest in no time; but I stuck reluctantly to my rule—no lifts except in vile weather—and we made plans to meet in the capital. He scorched off with a wave and after farewells at the Mayor’s I collected my things and set off too. I kept wondering if all Hungary could be like this.

I would only add that it is historical sources like this that show what a pack of liars the liturgical reformers of the 1950s and ’60s were when they spoke of the laity as “mute spectators” who were alienated by or uninvolved in the Church’s liturgical life. There is abundant evidence of appreciation of and participation in the traditional rites of the Church. It simply didn’t take the activist and clericalist form that the reformers obsessed over.

I wish one and all a most holy Triduum and a luminous Easter.

They are and were liars. I'm a convert in 1977 when I was 22, so I can't speak personally of what things were like before the Paul VI Rite. But I find the Novus Ordo (both of which words, by the way, Substack's AI just tried to correct -- deep meaning) -- terribly boring. At least Benedict XVI corrected the purposely bad Englishing. And the Orange Diocese here in California almost always has reverent NO masses, at least as far as that is possible. I usually now try to attend the Traditional Latin Rite at St. John the Baptist in Costa Mesa, and find it numinous. Of course, the critics would say that's now, not then. Whatever. And all those guys from 1969 are dead. I also somewhere have a thick volume from the 1935 Seventh National Eucharistic Congress held in Cleveland. How joyful people were! And reverent. And they had huge families with a dozen children. Let's go back. Repeal the last 90 years!

What an amazing ability of description. So well written and enjoyable. Thank you for sharing ~ and blessings back to you!