A Musical Analogy for Antiquity, Development, and Deviation

Can Mussorgsky's "Pictures at an Exhibition" help us better to understand the difference between organic expansion and reformatory rupture?

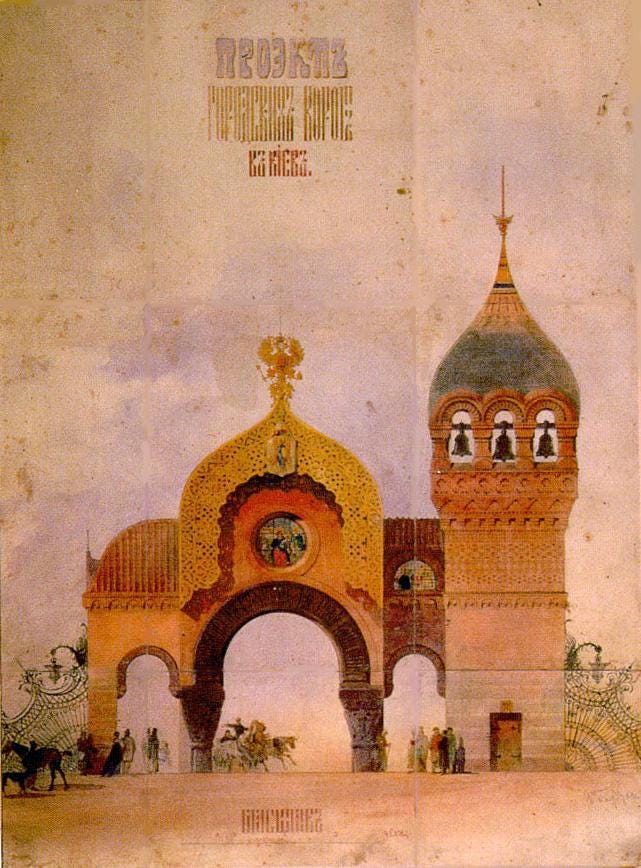

One day as I was driving to the airport (it was about an hour’s drive), I turned on the classical radio station, and to my sheer delight they announced that the feature piece for the next half-hour would be one of my all-time favorites: Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. This made the trip go very quickly, as I accelerated toward the Great Gates of Kiev — well, mundanely, toward the lesser gates of Eppley Airfield. And fortunately there were no police around, as I’m not sure I could have successfully explained the irresistible effects of this full-blooded symphonic music.

But wait a minute… was the piece on the radio really Mussorgsky’s?

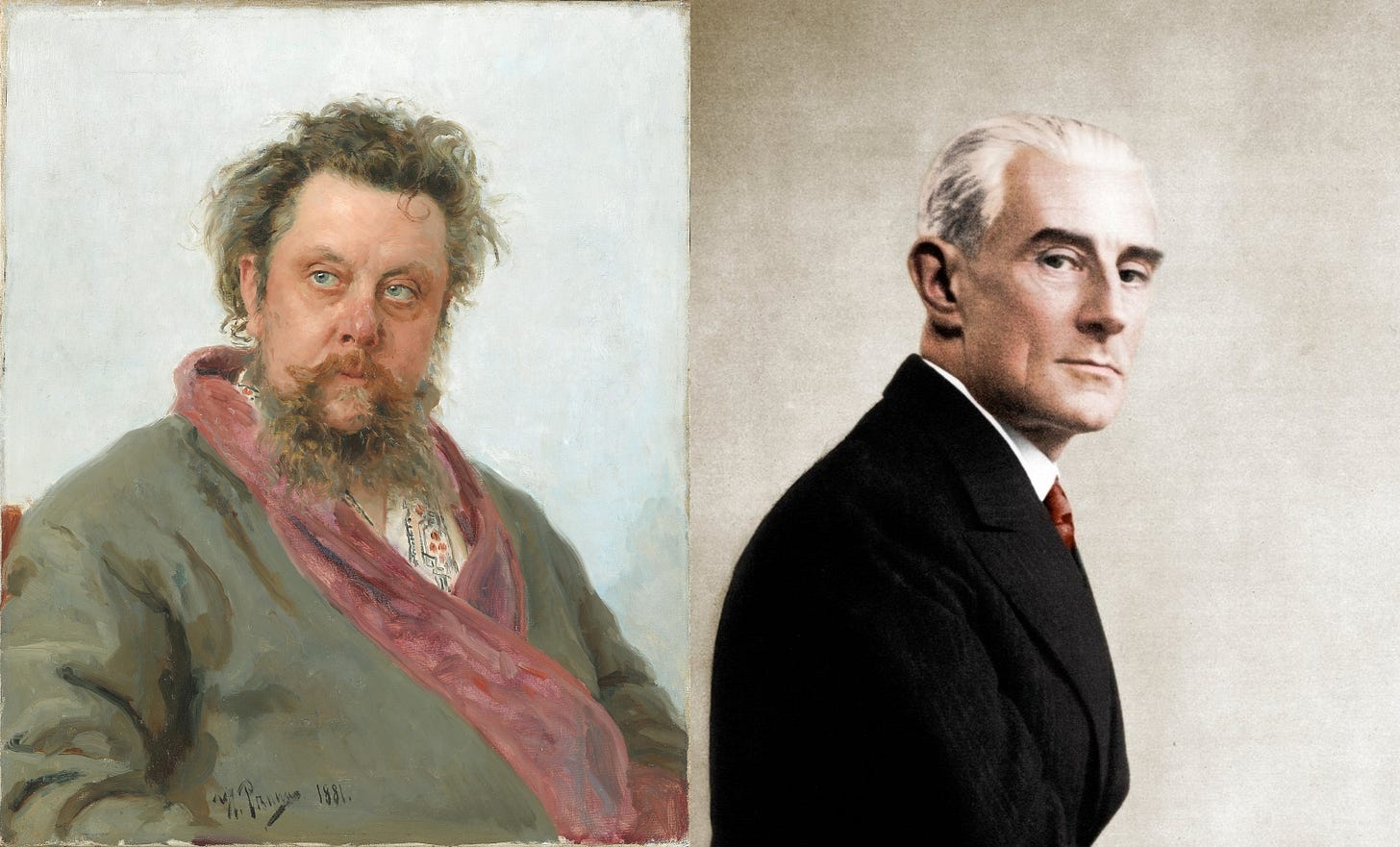

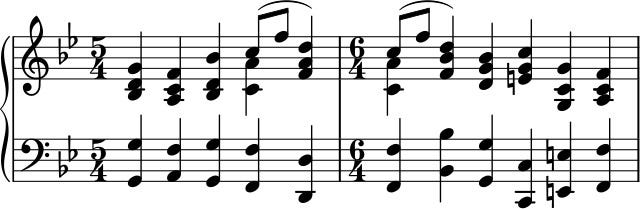

You see, Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881), one of the most unlikely and tragic of Russia’s many brilliant composers, had written Pictures at an Exhibition in 1874 as a lengthy virtuoso work for solo piano. In the interests of time (since the whole work takes anywhere from 30 to 35 minutes to perform), I will simply share the last movement, under 5 minutes in length, which has to be one of the most spectacular of all Romantic pieces. (The movement follows immediately on the preceding one, which is why it will seem to start a bit abruptly.)

Yet due to its rather strange format and unconventional musical language, this suite for solo piano may well have lapsed into the Oort cloud of forgotten compositions (a cloud that is much larger than the universe of widely known music) had it not been for the sheer magic worked upon it by a French “impressionist” composer, Maurice Ravel (1875–1937).

Ravel was only 6 years old when the Russian composer died at age 41, a victim of years of alcoholism. What I had been listening to on the radio was Mussorgsky’s piano suite clothed in the dense and variegated colors of a huge romantic orchestra in Ravel’s grand and glittering 1922 orchestration of it, a version performed far more often ever since. In Ravel’s hands, an already mighty piano work emerges into colossal majesty. This was what I heard that day on the radio station:

In fact, as far as I can ascertain from my reading, it was the popularity of the orchestral version that put the piano version back into circulation, when it might otherwise have vanished into obscurity.

Now, here is a philosophical question: Is the Mussorgsky-Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition the same as Mussorgsky’s original work?

In a way yes, in a way no. In the most fundamental sense, it is the same music — the melodies, the harmonies, the rhythms are carried over from the original score to the orchestration. But in Ravel’s hands, the original is everywhere embellished and amplified; it is the same and more than the same. You could say, it seems to me, that Ravel organically develops Mussorgsky’s original work: there is definite continuity but also difference, in the direction of expansion, complexity, subtlety, and grandeur.

Fast-forward almost fifty years, to March 26, 1971 (when I was, incidentally, only 4 days old in this world, having been born on March 22). The British progressive rock band Emerson, Lake & Palmer gave a famous live concert in which they recorded their rock arrangement of Pictures at an Exhibition, which they subsequently released as a bestselling record. When I was in high school, surrounded by people who listened to prog rock, my introduction to Mussorgsky came via this, ahem, version. At the time I loved the ELP performance. Later, I came to realize that what I loved most was what came from Mussorgsky, and that what I ended up disliking over time was the modern rock influence that distorted the genius of the original material.

Here is how the rock band interprets the Great Gate of Kiev. You will hear that lyrics, very “period” in character, have been superimposed.1 (I’m sorry that this will be rather painful to many of you, and if you like, you could skip ahead after a minute or so, just long enough to visit the scene of the crime.)

It was in thinking about this curious trio of examples — Mussorgsky, Ravel, and ELP — that the insight suddenly arose: This is a nearly perfect analogy for what happened with the Roman liturgy.

The Russian’s original piano version is like the early Christian liturgy in the centuries of persecution: simple, but all the essentials are already there.

The Frenchman’s orchestral version is like the fully developed medieval-Baroque liturgy: the solemn Tridentine Mass. It is obviously in continuity with the original but expanded and ornamented in every way. It preserves the original and, indeed, speaks most eloquently on its behalf. As someone once said: There is more of the year 200 in the living Latin rite that passed through every century down to modern times than there could ever be in a rite “drawn up” (to use Vatican II’s language) in the 1960s, even if they happened to use this or that scrap from the year 200.

The progressive rock version, with vernacular words added to it, is like the Novus Ordo: in some ways loosely based on what came before, but a deviation and a decadence. Progressive liturgists who advocate for the vernacular, for versus populum, for contemporary music — they are doing to the liturgy what Emerson, Lake, and Palmer did to Mussorgsky. Actually, ELP was more faithful to the original than the reformers were to the Roman rite, but for all that, the stark contrast in spirit among these three musical versions is, to my mind at least, a striking analogy for what has happened in the Church.

Incidentally, I do recommend listening to Pictures at an Exhibition — either in Mussorgsky’s original version for piano, or in Ravel’s orchestral arrangement. You can find many recordings online.

Thank you for reading Tradition & Sanity, and may God bless you.

Here are the lyrics (in their variations):

Come forth, from love’s spire

Born in life’s fire, born in life's fire,

Come forth, from love’s spire

In the burning, all are [of our] yearning

for life to be

And in pain there will [must] be gain

New Life!

Stirring in, salty streams

And dark hidden seams

Where the fossil sun gleams

They were, sent from [to] the gates

Ride the tides of fate

Ride the tides of fate

They were, sent from [to] the gates

In the burning all are [of our] yearning

For life to be

Now you're speaking my language, Dr. K. (I'll be waiting for your inclusion of King Crimson's "In the Court of the Crimson King" in a discussion of...well, something.) But on a semi-serious note: ELP is one a generation of bands comprised of members who had some technical proficiency and appreciation for classical music. The '70s (my time of youth) saw--in the sphere of popular music--an incredible explosion of music which quickly degenerated into trite schlock. (For example: Early Genesis and "The Musical Box" to Genesis 1978 and "Follow Me, Follow You.") Revolutions will inevitably produce, sooner or later, dreck. Example from literature" The Jesuit-educated James Joyce first writing the exquisite short stories of "Dubliners" and declining into the obscenities of "Ulysses" and the pointless, unreadable private joke of "Finnegan's Wake."

A fascinating and very apt comparison! Although superficially intrigued by ELP's work, I also realized this was primarily due to their drawing upon "real music" for their "source material", but that the whole *rock* idiom is ultimately ugly and disturbing. Yet, their music seemed to lie on the less "offensive" end of the spectrum, I would say.

It would be an interesting study - tho probably a multi-volume account - to trace the history leading up to how things like rock music and the Novus Ordo all erupted upon us in that era. Hard to believe they were completely independent trajectories.