An Instrumental Love-Affair

My Journey with the Renaissance Lute

In this article, I’ll tell you about how I made my way from nothing to this:

My One-and-Only “iPod”

Chop, splinter, crack, thud. I positioned the log, and raised the ax again over my head. My boots settled in the bark dust and wood chips around my feet, and the heavy blade split another log into kindling. The fall sunlight filtered through the trees into our backyard as the winter wood-pile grew. While the ax arced in my hands, music soared through my earbuds and into my 13- year old head. A life-long relationship was burgeoning.

Not long after, my first and last MP3-player bit the dust, and my short-lived era of doing tasks with earbuds stopped. Nowadays I listen to music with headphones only when I'm working on the computer; raw, unadulterated walking and working is definitely the way nature intended we go about our lives.

But the little blue screen of that 2013 MP3 retains nostalgia for me as the vehicle by which I was first introduced to – and captivated by – the Renaissance lute.

The two albums I was enamored of then, I still listen to regularly. They seem to get better every time: Rolf Lislevand's Nuove Musiche and Diminuito. But before I get into his artistry, I want to tell you about the lute's history, and my history with it.

A Short History of Twangers

At its heart, the lute is a variation on one of the few basic instrument forms. Every instrument can be put in one of three categories: objects that produce sound or pitch by being struck (percussion instruments); columns that produce pitch by having air blown through them (wind instruments); taut cords that produce pitch when plucked, struck, or bowed (string instruments). Every string instrument starts its life as little more than some guts on a stick. You find something that twangs, and then you attach it to something it can twang on. Then you make that something better at projecting the twang, and then you decide either to add more strings of different twangs, or to invent a method of changing the length of the string, with the same end result: variable pitch production. A number of Middle- and Far Eastern and aboriginal instruments have stabilized at this stage for centuries: twangers on a stick.

But since not everyone was satisfied with that, those old backwards people of who-knows-when kept tinkering with their sticks. Once their sheep were fed and enemies killed, not having any other important things to occupy themselves with (such as income taxes), someone (probably in the Middle East) invented the sound board: they put some thin pieces of wood together and formed an echoey, resonant chamber which amplified the twanging sound. Archeological evidence of these early lute-like instruments dates from as early as c. 3100 BC, and depictions of these instruments are visible in frescoes and carvings from Egypt’s 18th Dynasty to the time of Christ.

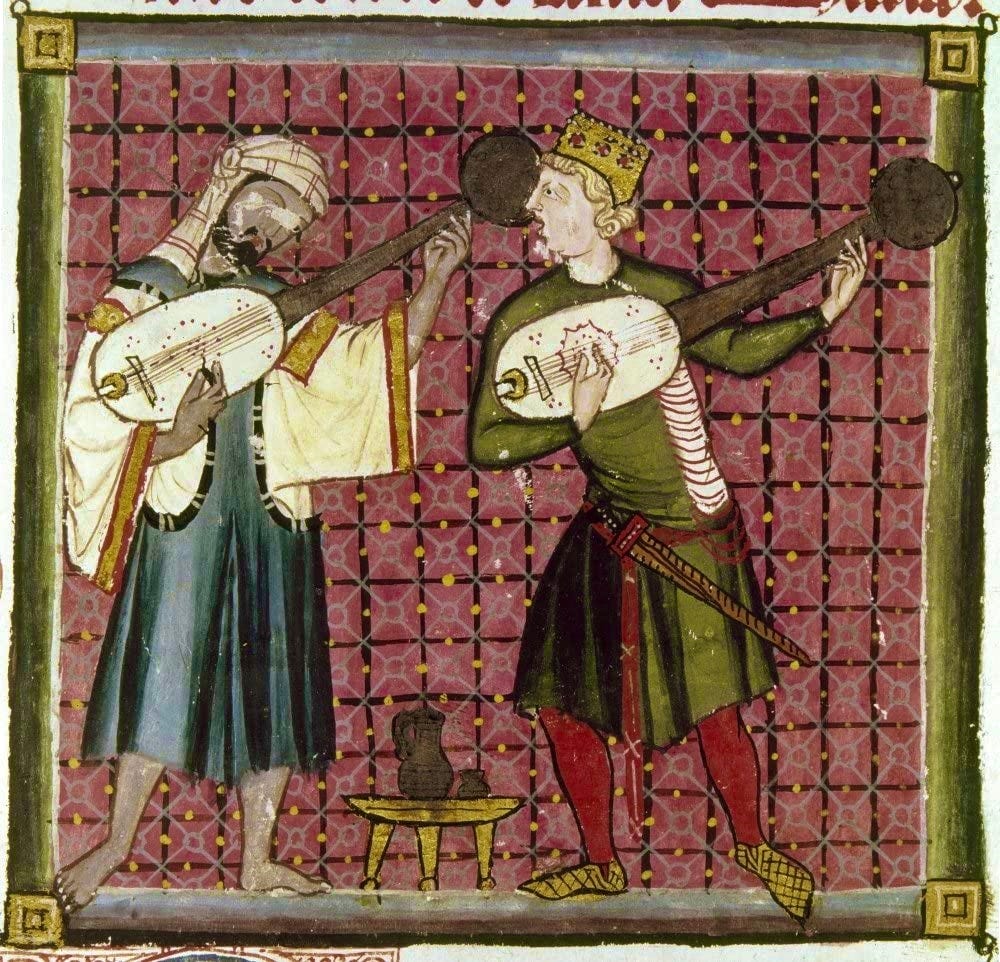

Under the Sasanian or Sassanid Empire (224–651), the last Persian empire before Muslim conquest, the small, almond-shaped Bactrian lute became known as the barbat or barbud, which in turn morphed into the Islamic oud or ud. The 8th and 9th century influx of Moors into Iberia brought more than just the oud, but their instrument-making was certainly one of their gifts to Europe; the goods of the luthiers (as lute builders in particular, and instrument makers in general, are called) spread to what is now France, and, through the troubadours, to the rest of Europe. Sicily was also an important point of encounter between Byzantine culture and western Europe, and perhaps the entry point of the lute into Italy.

At any rate, little music was specifically written for the medieval lute; but around 1500, it began to come into its own as a solo instrument. Throughout the Renaissance and Baroque eras, the size of the lute, as well as the number of strings it possessed, continued to increase. From the modest five-string medieval lute, the instrument eventually found itself in the grand form of 14-string archlute and theorbos, sometimes five or six feet long due to an extended neck for longer, deeper bass strings.

The lute was the Renaissance equivalent of the modern-day acoustic guitar: they were everywhere, from court bedrooms and ballrooms to taverns and soldier’s quarters. Each country developed its own version of the lute—or at least its own distinctive repertoire. As far as I can tell, a player today needs at least four or five different lutes to be able to play all the music written for it during these periods.

Anatomy of the Lute

Before I go further, a few terms should be defined and explained. The lute is double-strung, that is, instead of having one string for each different pitch, there are two strings, plucked simultaneously and sounding together as one. The modern mandolin is also double-strung. One reason for this, among others, is the fact that the historical gut strings produced a rather soft sound, and so, two strings weakly sounding together resulted in an increase in dynamics. Even so, the lute is a very quiet instrument, meant for intimate spaces.

These sets of paired strings are called courses. So a “ten-course lute” means a lute with ten sets of two strings—ten pitches to pluck and fret. Technically, that should make it have twenty strings, but the highest pitched string is usually not double-strung since the higher pitches are louder and it is easier to play fast passages in the melody on a single string. So in reality the ten course lute has nineteen strings.

The body of the lute is also called the bowl, given its curvature. The frets are called…frets. But unlike the metal ones on a modern guitar, they are made out of gut strings tied around the neck. This allows them to be moved around for tuning, and replaced once they wear out.

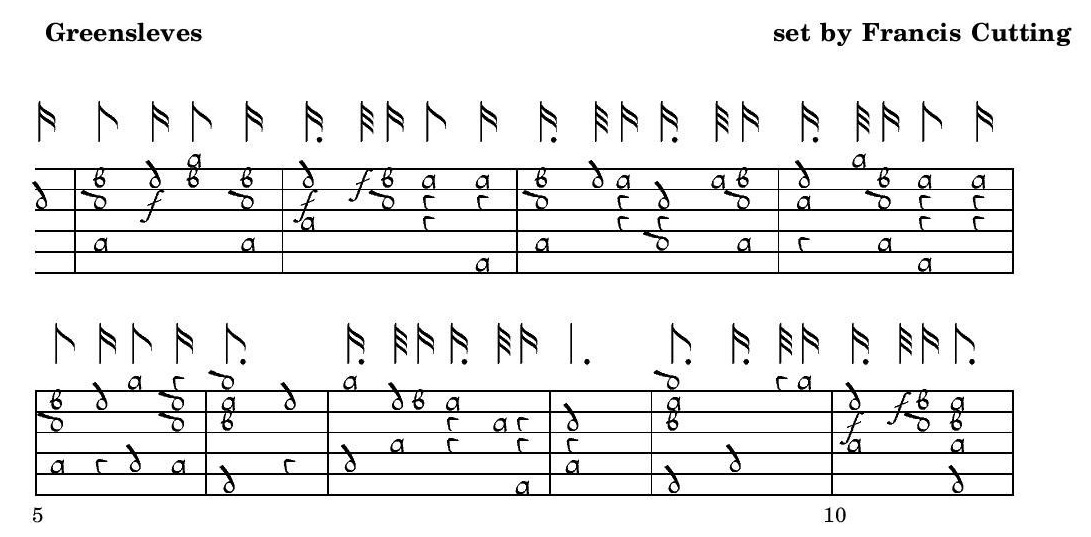

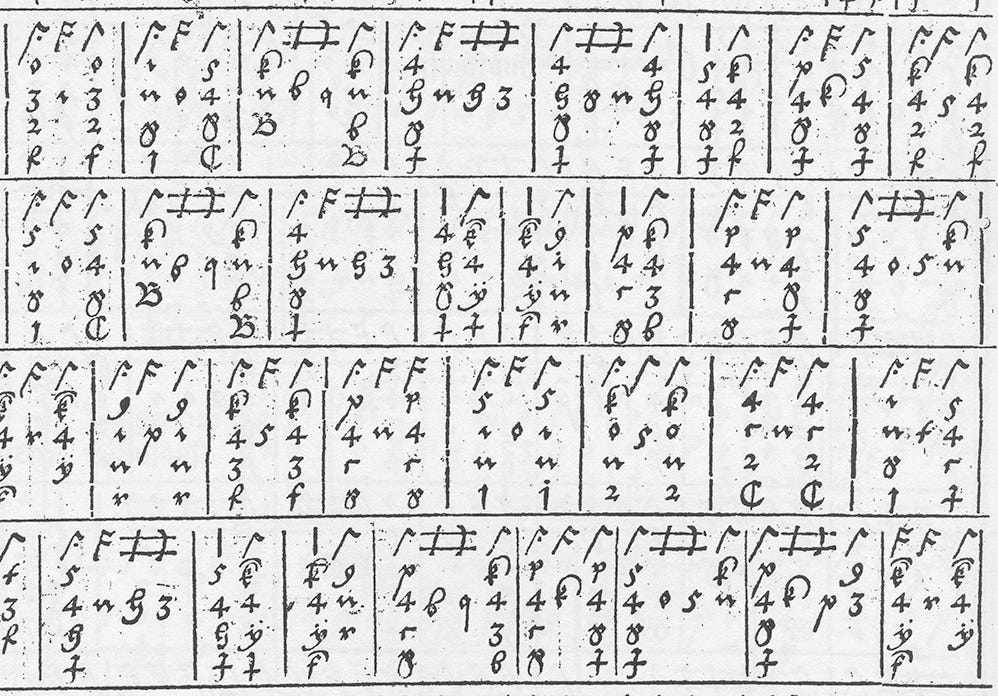

Lute music is notated in what is called tablature. Rather than indicating notes on an imaginary sound-space called a staff, lute music indicates where you put your hands on the instrument and which strings to pluck—and therefore only indirectly tells you what notes will be sounded.

Although it looks thoroughly esoteric, it is in fact a very efficient and useful system: bypassing theory, it tells you where to put your fingers. Thus, someone with no music theory can sit down, not even know if he’s playing a G or C chord, and yet still play a complete piece of music. And since there are sometimes multiple ways of getting the same note on a fretted instrument—you could get a high “a” by fretting the first string on the 2nd fret, or by fretting the 2nd string on the seventh fret—tablature allows the lute composer himself to figure out which hand positions make the most sense instead of putting that burden on the player (a burden classical guitarists must bear since they play from notation, not tablature).

Essentially, tablature consists of lines representing the strings of the lute. Letters placed on the lines indicate both which strings to pluck with your right fingers and which frets to put the fingers of the left hand on. So a means open string, b means first fret, c second fret, d third fret, and so on. The rhythm signs are put over the tab. And off you play!

You might have expected this already, but since the wild and wooly Renaissance lacked the abundant blessings of the world-wide-web, top-down standardization of tablature was impossible. Consequently, there is an English system of tablature, and a French system (which is just the English, only written upside down), an Italian system (which is the same as the French, except that it uses numbers instead of letters to indicate frets!), and, finally, a German system, which is completely different, convoluted, and unintuitive (like later German philosophy), and which hardly anyone knows how to read.

Back to My Love Story

Now that I’ve given an overview of the lute, let me return to my own personal history with this lovable instrument. Having imbibed Rolf's virtuosic lutenizing for a couple of years, and, now as a teenager, having largely taught myself the Celtic Folk Harp that I had begged my parents to buy me as an 8-year old (and in which, after it had been acquired, I summarily lost interest for several years), I was now in a position to beg my dad for… a lute!

Given that lutes are rather pricey, we rejoiced when online research revealed the existence of the Lute Society of America (LSA) and the English Lute Society, both of which run rental programs aimed at making it easy for young people and interested amateurs of all ages to begin learning this rare instrument. Unlike guitars, you can’t just buy a lute from your local music shop or off of Amazon; every real lute is custom-made, entirely by hand, by an individual luthier. (There are a few cruddy mass-produced models floating around; these are hardly more than stage props.)

By November of 2015, I had a seven-course student-grade lute in my hands (indeed, hardly ever out of my hands), and I had started taking skype lessons with Maine-based lutenist Timothy Burris.

Here is 17-year-old me banging out an Elizabethan tune on that first lute. Part of my dad’s CD collection is in the background. When a friend shared this with Nigel North, one of America’s top three or four lutenists, he is reported to have said, “I’m impressed. He should come study with me. But he needs to learn how to tune better.”

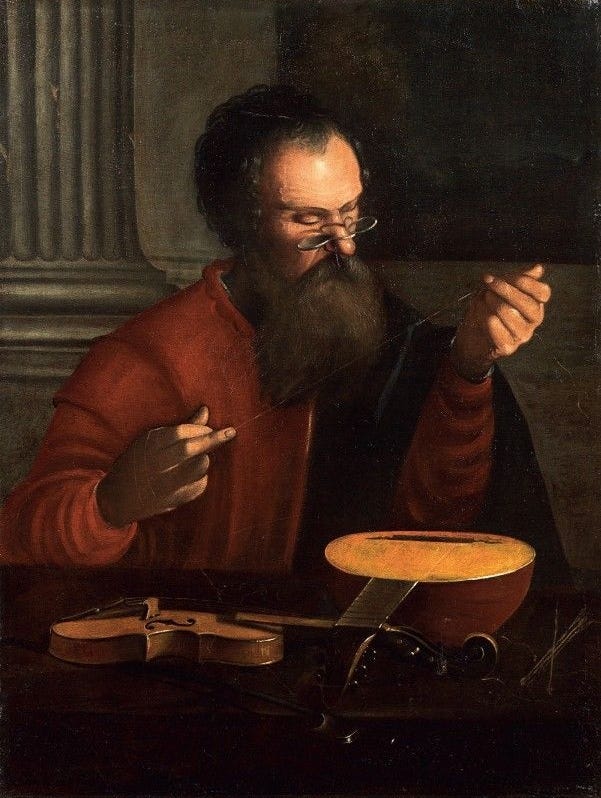

Ah well, as one historical figure from the baroque said, "If a lute-player has lived eighty years, he has surely spent sixty years tuning." Since the pegs are not geared but friction-fit, the tuning is difficult. Since the strings are thinner and more delicate, they go out of tune more easily. One of the most frequent questions I get about my lute is, “Why is the peg-box bent back?” As far as I understand, this is because the nut—the little white bar at the top of the neck which the strings vibrate from—was originally only friction-fitted to the lute, rather than glued. The 90 degree angle of the strings turning over it helped keep it in place.

Since the wood a lute is made out of is thinner, it easily shifts with temperature, and so on. I’ve never strung my lute with authentic gut strings, which some swear by as just that much more subtly beautiful in sound—and even more sensitive to humidity. You boil a pot of pasta in one room, and your gut-strung lute in the next room goes completely out of tune. My synthetic strung one only goes partly out of tune.

Having progressed for two years on this little lute, I was ready for an upgrade. Fortunately, a premium-quality instrument had just been acquired by the LSA rental program, and before 2017 was over, I was playing a $10,000 instrument built by one of the world’s most revered luthiers, the Barber and Harris firm on Peacock Lane, London.

This beautiful instrument was an archlute – a development of early Baroque Italy, where the limits of the lower bass strings on a regular lute were surpassed by adding an extension to the neck. The longer the string, the lower the pitch. This archlute was about 5’ 2” or so. With a rich, warm bass register, and a silky-smooth upper register, I was inseparable from this… very advanced twanger.

Here’s a recording of a Baroque Italian piece I made with the archlute in 2018:

This fine instrument was made from quite the catalog of exotic woods. The back of the archlute was Bolivian Santos rosewood (now illegal to source because of overharvesting but prized in the instrument-making world), the soundboard of German spruce, and the neck of Germanic limewood. A diverse company of woods from Merrie England furnished the other parts: poplar and beech neck components, persimmon fingerboard and tuning pegs, and a bridge made of holly.

Because the archlute was so long and its case unwieldy — you can see that well in the photo, where the case is on the floor next to me — traveling with it was a little ordeal: it stretched from the dashboard of my dad’s Taurus, threading between the front seats and resting in the back middle seat. It was a Three Stooges operation to get it in and out of the car.

And here I have to give a shout out to my dad for his constant support as a patron of the arts, always willing to find out if renting a lute was even possible, then trucking it around, and generally doing anything and everything from pulling out his wallet when the need arose to printing huge amounts of lute tab for me and spiral binding it!

Despite the difficulties of transporting it, the archlute still made an appearance at several choral concerts with the Wyoming Catholic College Choir in Lander, Casper, and Sheridan, Wyoming, as well as at a few liturgies for the College chaplaincy. One year, a student and I prepared a motet for the feast of the Annunciation – an arrangement of a vocal piece where the lute played the lower three “voices,” while the soprano sung her part as the “melody.” This way of arranging polyphonic music for a soloist and an accompanist was common in the Renaissance, and was known as “intabulation”—putting another musical composition into lute tablature.

This appearance of the lute in a liturgical setting – a familiar sound in the instrumentally rich Renaissance period – gave rise to some jokes about “lute Masses” in contradistinction to guitar Masses. All I can say is, I wish there were more lute Masses!

Happily, I discovered the music of contemporary lutenist Christoph Dalitz while in possession of the Barber and Harris archlute, and was able to record several of his sonatas with the instrument. Dalitz is a master of composing in the Baroque style, and has produced music for both the lute and voices that is delightful to perform. I recorded these two sonatas in my freshman year of college, and while the recordings are not perfect, the music is so good that it deserved to be shared, so I put them on Spotify.

Those years of romping care-free across the strings of the archlute were not to last, however. Once I had decided to try my Benedictine vocation in Europe, I had to send the rental instrument back. I spent the next four years cut off from all contact with the lute. But once I decided to leave the monastery, I knew re-acquiring a lute would be top priority.

Back in the states, I started searching the very small “used lute market” via the very small and tightly knit world-wide community of lute players. I ended up purchasing a fantastic ten-course lute made by Martin de Witte, only lightly used, from a player in Hungary. This Hungarian gentleman, only a lute player in his spare time, had decided it was the one of his three lutes he could live without, since he needed to fund the transformation of his basement into a micro-winery and wine cellar. I got a lute, and he a wine cellar. A good and fitting deal, if you ask me.

Right now, this brightly-sounding instrument allows me to play a wide range of repertoire, from this Renaissance tune to Irish jamming:

A lovely lute-tasting experience occurred this past summer when I attended an early music festival. There I got to play Greensleeves on a beautiful bass lute, test-drive some vihuelas (a type of lute-guitar), meet a theorbo, and participate in a medieval jam sesh, as well as enjoy professional concerts and masterclasses. The most recent escapade with my lute involved performing in the debut concert of Los Angeles-based ensemble Musica Transalpina. Here’s the Kyrie from the five-choir Mass (that’s me over on the right side, next to a theorbo player):

Today, I continue to try to find time to play my ten-course lute, and await a new archlute of my own, commissioned from a luthier in Finland. I try to post something on my YouTube every few months, and hope to record a full album of folk and Renaissance tunes in the near future. (I could use the lingo, “like, subscribe, and follow me on YouTube and Spotify” to help these endeavors continue but…so far I’ve made a whopping $4 from the singles I’ve released on Spotify. If you ever want to discuss inviting me to give a lute concert and a presentation on music somewhere, please contact me. And if you enjoy my Spotify releases, do add them to your playlists—they are also on Amazon music, I-tunes, etc!)

When I began this article, I intended to say something about different periods of lute music, share videos of more proficient lute players than myself, and comment on Spotify lute playlists I’ve created. But now that this article has grown to a decent size, all of that will have to wait for another post in the near future. For the time being, I’ll share my general lute playlist as well as my Rolf Lislevand one, so that you are already primed for my commentary on some of these tunes.

Thanks so much for reading! If you enjoy my work here on my dad’s Tradition and Sanity Substack, please consider giving me a small tip via my buymeacoffee.com page, where you can make a one-time or recurring donation to support my writing. Thank you!

These last two guest posts on music have been salutary for me.

This time I was struck by your mention of the different woods used in making the loved lute. It reminded me of the history of shipbuilding. Our ancestors were neither ignorant nor without technology, and we must not forget it.

The (slow) reel reminded me that the folk of earlier times knew how to make their own entertainment. Our times seem the poorer for having forgotten this.

And though I have for years liked (slow) baroque solo pieces transcribed for classical guitar or the lute—which is even more mellow—these were also God-sent during bouts of anxiety over several years. They are instruments which seem incapable of rattling even my nerves. Such musical thoughts draw my fitful senses into their order.

I also find there is something strangely reassuring about fret and string noise. It seems like the instrument whispering back to the solo artist…no doubt David’s harp was not brassy when he played for Saul.

(Symphonies and great choral works are for other times and can elevate the weary soul.)

Thanks for prompting me to appreciate your music, and the role of music in a good life.

If you only knew how much I appreciate you plucking up the courage to educate us on this! ;)