An Irenic Response to an Orthodox Convert’s Critique of the Papacy

The Orthodox are fortunately inconsistent, but unfortunately still separated from the common father of Christians

Michael Warren Davis is an eloquent writer. I have long enjoyed reading his work. With many fellow Catholics, I regretted his decision to leave the Church of Rome for Eastern Orthodoxy — a path trodden nowadays by a small but vociferous number of traditionally-minded believers who feel they can no longer make sense of the claims Catholicism makes for itself and who believe they have found a timeless repository of authentic tradition in the East. As one who spent a number of years worshiping among Greek Catholics in the Byzantine rite, and who has devoted his life to arguing against the spirit of iconoclasm and modernism that has seemed to grip the West, I can truly sympathize.

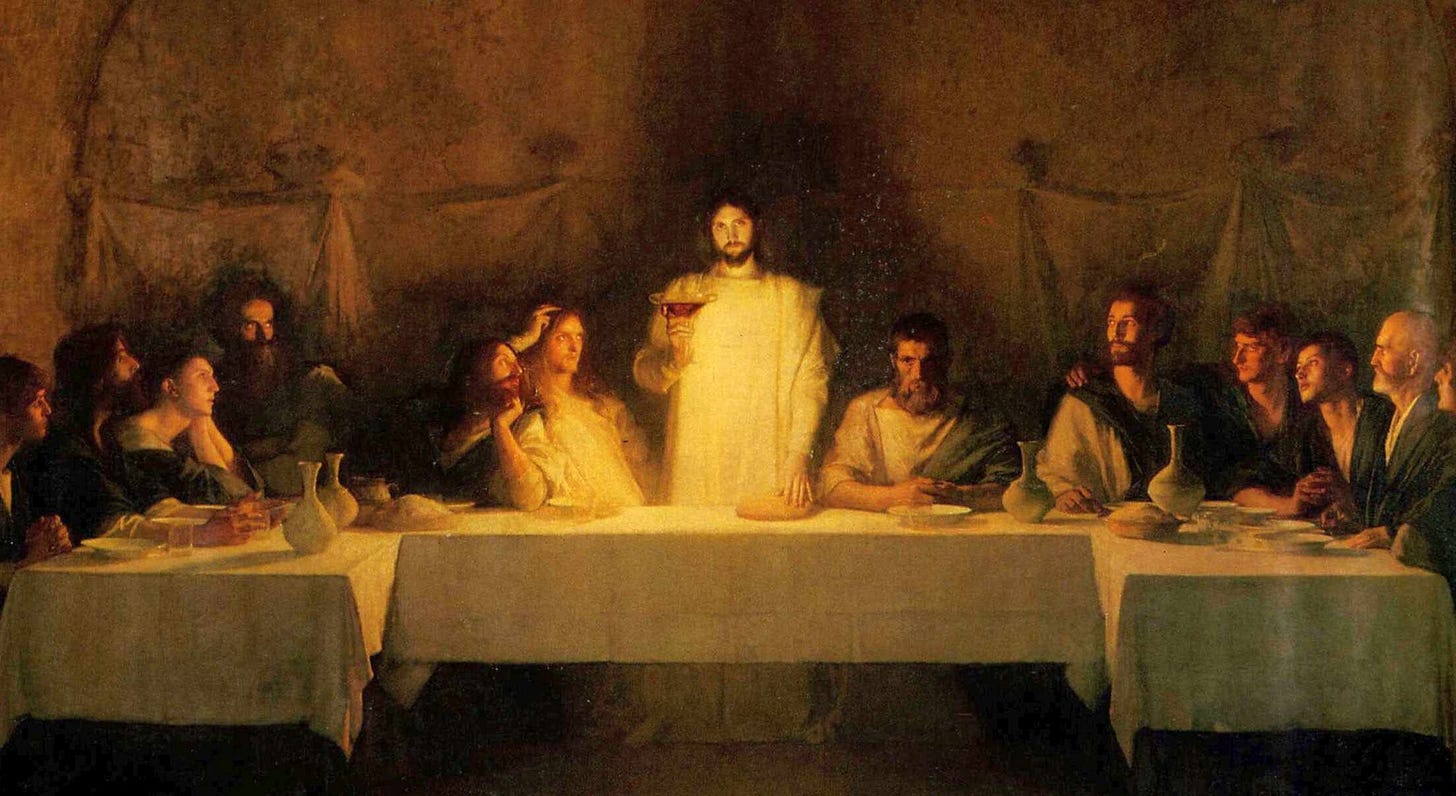

In a recent post at his Substack The Yankee Athonite, Michael defends the Orthodox position that Christ alone is the head of the Church (for what could you be lacking if you have Him?). There is no need for papal primacy, for a visible head, since the Church already has a Head, the God-Man, who is really present among us in the Holy Eucharist, and who gives His faithful the Holy Spirit to lead them into all truth. With the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit vouchsafed to us sacramentally throughout our whole life, why would we seek an external divine authority that stands, as it were, in their place (as a “vicar” or substitute)?

There’s certainly a lot one could say in response — that is why so many tomes have been written in the millennium-old back-and-forth between East and West. For readers who are eager to understand the mind of the Eastern Fathers of the Church on the papacy, which looks to me a lot more like what the Catholic Church teaches and a lot less like what one finds among the post-schism Orthodox, I recommend two books in particular: Adrian Fortescue’s old classic The Orthodox Eastern Church and Erick Ybarra’s recent work The Papacy: Revisiting the Debate Between Catholics and Orthodox. (I agree with Timothy Flanders’s judgment that Ybarra’s work shines for its intellectual humility, honesty, rigor, and lack of point-scoring triumphalism.)

Here, I’d like to offer some thoughts of my own to this very common Orthodox line of argumentation. In my opinion, the problem with it is not that it proves nothing or too little, but that it proves far too much. I think, at root, it actually gives up on the entire idea of the visible Church and the sacramental-liturgical life. But are not the Orthodox known above all for the gorgeous liturgical life and their rich teaching on the “mysteries”? How could I say that their rejection of papal primacy amounts to undermining the rest of the Church? I will give my answer below. I don’t think the Orthodox live in exact accordance with the principles articulated in anti-Western polemics. There are older and deeper principles at work among them that prevent certain false ideas from bearing the bad fruits they might bear in a consistent rationalist (and that is not something one could ever accuse a devout Orthodox Christian of being!). These theological principles — supported by a healthy inertia that holds on to monuments of tradition, something the restless Faustian West would benefit from imitating — should draw a fair-minded Eastern Orthodox believer into the Catholic Church, joining one of the Eastern rites in communion with the Pope of Rome.

With that preface, here is my response to Davis’s essay.1

Dear Michael,

I think what you are forgetting here is the history of the first millennium when there were many notable cases in which Roman Pontiffs were consulted as final authorities or intervened decisively to solve a difficulty.

Christ in the Holy Eucharist is blazingly glorious — but also conveniently silent. That is, he does not directly answer our questions about the indissolubility of marriage (in difficult cases) or in vitro fertilization or the intrinsic evil of homosexual relations. Yes, one can find relevant passages in Scripture and the Fathers, but if they were perfectly obvious to everyone, we wouldn’t have a thousand Protestant denominations, some liberal Catholics, and some progressive Orthodox disagreeing over them. If there is not a court of final appeal, hard cases like this — which can mean the difference between eternal life and everlasting death — have no real solution.

Moreover, there is the principle of redundancy and maximalism at work. Christ our Lord gives us many means of knowing and serving Him because He is generous, not because He is desperate. The problem I have with the logical form of your argument (“If we have X, why would we need an image or representative of X?”) is that it could be used to pull down the entirety of apostolic, sacramental Christianity. A Protestant could say to an Orthodox: “Why do you need the Eucharist, when Christ gives you His Holy Spirit in baptism? What more could you want than the divine Spirit of Christ?” Or: “If Jesus is with us until the end of time, present in your heart and mine by faith, why would He need to come among us as food and drink? That seems less intimate, less crucial, than being in our hearts by faith.”

Many versions of such objections could be crafted. The answer is not, He had no choice, but He wants to give us more, ever more. A man can be saved by baptism alone, but the Lord chrismates and communicates him as well, because the good is diffusive of itself — the infinitely generous will never stop giving, in time or in eternity. One could be saved by perfect repentance but the Lord gives us Confession; a baptized man and woman could no doubt have made a go at living together and raising a family, but Christ in His generosity decided to elevate this relationship to a grace-giving sign of His union with the Church, so that even the most mundane aspects of life could be supernaturalized.

Or someone could object: “Why do you need Our Lady to intercede for you? Isn’t Christ, the one Mediator between God and man, sufficient and more than sufficient?” Our answer is not that He had to do this, as if His hand was forced, but because He loves intercessors and multiplies them for His glory. Mother Teresa famously quipped: “Saying there are too many children is like saying there are too many flowers.” Well, saying there are too many brothers and sisters united in a common prayer is like saying there are too many saved souls. There are so many examples of this luxurious divine largesse — like the “wastefulness” of the rich perfume spilled by St. Mary Magdalene — that I could fill pages with them.

And so, when the Orthodox says to the Catholic: “If we have Christ, or the communion of the Church, or the consensus of the Fathers, we don’t need a Pope!”2 The response, again, is: maximalism and redundancy. Sometimes the words of Christ, as luminous as they are, fall on deaf, stubborn, heretical ears. Sometimes the words of the Church Fathers are not as clear or unanimous as we might wish. Sometimes people receive Holy Communion for years and are still deceived about this or that error or vice. It seems like a perfectly sane response to give the Church a visible, audible head who can decisively intervene when intervention is needed.

Engineers understand the principle of redundancy. They build their systems to have backups at every stage so that if something that normally doesn’t fail happens to fail, the entire system does not fall apart. As St. Vincent of Lérins argues, normally Scripture should be enough for those who live and breathe the Catholic Faith by the gift of the Holy Spirit. But heretics twist Scripture, so there is need for the unanimous consensus of the Fathers. And if even that should fail, there are ecumenical councils. So far, so good: the Orthodox are right alongside us, affirming the Divine Engineer’s redundancies. The papacy is simply one more of these “redundancies”: normally we do not need the pope to weigh in on this or that issue, until it gets out of hand. He is a court of final appeal when bishops, metropolitans, or even primates cannot resolve their disputes.

But is this not a “hard saying,” very much akin to Jesus saying His flesh would be real food and His blood real drink? Many who had followed him walked away, shaking their heads, for surely, he must have lost his mind — talking like that! Similarly, when Jesus says to Peter: “Thou art Rock, and upon this rock I will build my Church,” “But I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not: and thou, being once converted, confirm thy brethren,” and “Feed my lambs, feed my sheep,” surely he is promising too much to this wavering, hot-headed, cowardly follower of his! Such grandiose promises hardly befit mortal flesh and blood. But just as Our Lord meant what He said in John chapter 6, and He has power to fulfill it, so too He meant what He said in Matthew 16, Luke 22, and John 21, and He has power to fulfill it — not only for Peter, who would soon die and receive his reward, but for every bishop who succeeds Peter in the Apostolic Chair of Rome, the first among all the ancient Sees. After all, transubstantiation and papal primacy are not remotely as “hard” to accept in faith as is the world-shaking, cosmos-transfiguring event of the Incarnation of the Logos, which is their fundamental prerequisite but, even more importantly, their dvine model.

Cardinal Charles Journet offers this penetrating commentary on the interconnectedness of the Incarnation, the Eucharist, and the Petrine primacy:

What a union of apparently contradictory attributes! What a difficult saying seeking a welcome in our hearts! That Peter, who is one man and who can inhabit only one place, was chosen as head of the Church, which is divine and universal! Nevertheless, in Christianity, this saying is not seen as something strange or foreign to the faith. In a sense, we could say that it sounds to our ears like a familiar and expected message. It formulates a great mystery; but this mystery is in no way new.

In one of its applications, it is the presence of a unique, breathtaking mystery in which Christianity consists: God willed that divine things be enveloped in feebleness, infinite things held fast in space and time. In Luke 1:26–27, at the moment of the Incarnation, we see that all the geographical and genealogical details have been massed together in order to announce to us the descending of Eternity into a moment, Immensity into a place, spiritual Liberty into the constraints of matter. The very Creator of the entire universe was born a small child on our planet and later declares that his flesh is food and his blood drink: these words were spoken in order to unite, but, seeming to many hard and intolerable, they divided. Finally, he proposes a mystery, no doubt inferior but analogous, and he chooses (we could not say his successor — this would be blasphemous) his vicar, that is, someone to be the authorized spokesman of his teaching and the depositary of a power until now unheard of — a weak man, whose misery Christ knew well and whose denials he publicly foretold.

The Incarnation, the Eucharist, the primacy of Peter, these are the directed manifestations and stages, as it were, of one and the same revelation. There is a worldly wisdom that immediately rejects this revelation. And there is another wisdom that begins to be Christian, begins to believe in the Incarnation, but then, a little farther on, becomes disconcerted before the mystery of the Eucharist or the mystery of the primacy of Peter and makes no further advancement. It seems to forget that God is God, that he passes through matter without being diminished, that, on the contrary, he makes use of matter and transfigures it.3

One might put it this way: within the very conception of Christianity, in the mind of its author, the Incarnation was destined to ripple out into the Eucharist, and the Eucharist was to be the sign and cause of the unity of the Church governed by Peter. It is impossible to be Catholic — indeed, impossible to be fully Christian — without believing in the unique visitation of the world by the Son of God made man, without honoring the singular woman He chose as His Mother, without accepting His enduring presence among us as our Emmanuel or God-with-us in the Blessed Sacrament, and finally, without remaining subject to His Vicar, His representative on earth. (Why there must be such a representative is well expounded by St. Thomas Aquinas here.) There is a tight logic to the fundamental elements of Catholicism: they stand or fall together. Christian reform movements that began by rejecting the papacy ended up, over time, rejecting the Real Presence, the prerogatives of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and, at the limit case, the Incarnation itself. All of these are various forms of one and the same “scandal of the particular”: the entrance of God into our material world in order to seek and to save that which was lost.

Now, when I said at the beginning that the Orthodox don’t live in exact accordance with the principles articulated in their anti-Western polemics and that there are older and deeper principles at work among them, this is what I mean. The Protestants rejected the papacy, and in due course, rejected the Real Presence and the prerogatives of Our Lady; some even came to reject the Incarnation. The conceptual path from Lutheranism to Calvinism to Unitarianism to atheism is not difficult to trace. However, the Orthodox reject the papacy and still maintain the other dogmas. The reason they can do so is that they still believe in the apostolic, hierarchical, sacramental nature of the Church. And this means implicitly they must be assuming the succession of St. Peter, the pyramidal perfection of the hierarchy, and the visible sign of its invisible head, while expressly denying it and resisting its claims on them. Put differently, if the Orthodox accept that each local church is headed by a vicar of Christ under the visible form of a bishop who is father of the local faithful, they can have absolutely no basis to deny that the one Church of Christ on earth, called by the Fathers the Catholic Church, is headed by a vicar of Christ under the visible form of a bishop who is the father, or papa, of all Christians.

This is not a merely human logic; it is the necessary unfolding of the Logos of the Ekklesia, the harmony of the local and the universal, of the many and the one — of immediate incorporation into Christ and hierarchical mediation of Christ. “As above, so below”: the hierarchy on earth must be a full and faithful reflection or icon of the hierarchy in heaven. Unlike the Protestants, the Orthodox assent to these mutually implicative, dynamic antinomies — but then suddenly stop short, unwilling to embrace the conclusion of the premises they hold. Their beliefs point to a hidden linchpin that they deny; instead they point to Christ alone (solus Christus) as their ecclesial linchpin much the way a Protestant points to the Bible or to faith in his heart (sola Scriptura, sola fide). Both are mistaken, but in different ways — the Protestant by having cut himself off from the Church, the Orthodox by holding on to a Church denied its full embodiment.

And I regret this all the more because I am convinced that the Latin Church, especially at this time of crisis in the West in general, would stand to benefit immensely from the presence, within it, of the faith, liturgy, witness, yes, even stubbornness, of Eastern Christians. Speaking in earthly terms, we are diminished on both sides by the lack of communion, for Catholicism has seen the growth of a hyperpapalism that diminishes genuine diversity, subsidiarity, coresponsibility, and attachment to venerable tradition, while Orthodox Churches have suffered from phenomena — autocephalism, ethnophyletism, caesaropapism, and pluralism — that diminish their Catholicity, their reflection of the one Immaculate Bride of Christ, the Church in her heavenly splendor.

Now, I am fully aware that there are times when popes themselves act against their own God-given mission, and that is what we are seeing in spades in recent decades: popes who arrogantly interfere with or cancel out traditions, who teach erroneously (e.g., Francis on communion for adulterers and blessings of homosexuals), and so forth. I admit all this. It’s a huge scandal, a massive departure from wisdom. It is not contrary to what the Church recognizes as possible for papal deviation, but it remains lamentable and a true stumbling block to any reconciliation (how could it not?). I am as painfully aware as anyone of the limitations and deviations of certain individual popes throughout history. Christ did not give us inerrant or impeccable bishops at any level. He only promised that the supreme shepherd of the flock on earth would not define error or anathematize truth, even as an ecumenical council cannot define error or anathematize truth.

Nothing you argued seems to me to be a decisive strike against the papacy as its powers are narrowly defined by Vatican I. That the pope should be infallible when he speaks as Vicar of Christ to the universal church on a matter of faith or morals seems to me to be eminently reasonable, and the fact that it is not often seen in history4 also stands to reason: most of the time, the “nuclear option” against heresy is not needed. Your summary “the pope is infallible except when he isn’t and he must be obeyed except when he shouldn’t be” is glibly said but correct. It is obvious that he is normally not infallible, and that his commands are to be obeyed according to the standard rules of morality (e.g., if the pope, whose job it is to defend and hand on tradition, tells you to deep-six it, you don’t follow him in that regard).

Papal infallibility is, as I hope you learned while a Catholic, not a blanket spread across all that a pope says or does, but a highly delimited charism. It may sound to some ears like magic, but certainly no more than our sacraments would sound like magic to any nonbeliever’s ears! If we believe Our Lord can assume human nature to His person; if we believe He can transform bread and wine into Himself; surely He can make use of a bumbling human being to utter the truth or condemn error at the moment it is necessary, and He is no less able to strengthen faithful Catholics around the world to resist whatever momentary crimes or non-definitive errors spring up like weeds from time to time in the garden of the Church.5

Given my work, you know that nothing I have said above should be taken as triumphalistic papalism. If anything, we Catholics should be on our knees in sackcloth and ashes, begging to be delivered from a “style” of papacy that is corrupt and corrosive. Yet by the same token, we won’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. All the principles of Catholicism are willed by Christ and cohere in the unity He willed for His Church, as we saw Journet so beautifully argue in regard to three mysteries. And because of the blessed redundancies of divine generosity, we are not helplessly crippled if, for some period of time, one of the means of assistance is not available — whether it be sound papal teaching and governance, or access to liturgy and sacraments for confessors thrown in jail. The Lord in His Providence has ensured that His grace will reach us and remain with us if we are not at fault.

Yours in Christ,

Peter Kwasniewski

A rough draft of the following was left in a series of comments at MWD’s Substack, but I have developed it considerably. MWD replied to my comments with counterarguments, but as I do not think those counterarguments actually refuted my main points, I have not engaged them here; interested readers may find them over there.

A digression: your antipapal arguments can be turned against Christianity as such. If Christ alone is head of the Church, why has He (seemingly) done such an abysmal job of it—letting by far the larger part of the Church fall away (the Western half, on your account); letting the See of St. Peter fall into heresy; letting the Orthodox splinter apart and often bicker or excommunicate one another and with no realistic possibility ever of an ecumenical council, contrary to the indisputable practice of the early Church? Let’s push this further: if the Eucharist is sufficient unto itself, why does it not produce saints in all who receive it? Why are there so many sinners among daily communicants? Is universalism so prominent among the Easterners because it’s the only way they think they can rescue the universe, last-minute, from being an absurdity? The attack you range against the “usefulness” or “uselessness” of the papacy is an attack that can be equally ranged against every aspect of Christianity and even of theism. It’s a very sharp and versatile knife that cuts in all directions.

The Theology of the Church, trans. Victor Szczurek, O.Praem. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2004), 128–29.

See Joy’s Disputed Questions on Papal Infallibility for a realistic assessment: several hundred times over the centuries, and certainly more than twice in the past couple of centuries.

For a deep dive into these topics, I recommend two books: Ultramontanism and Tradition: The Role of Papal Authority in the Catholic Faith and John Joy’s Disputed Questions on Papal Infallibility—the latter of which is a masterpiece of theology, highly accessible and totally satisfying.

Those who depart Catholicism for Orthodoxy are understandably enamored by its embrace of beauty and tradition. Some eventually figure out the grass is not greener in Orthodoxy, but returning to Catholicism requires a healthy dose of humility - to admit one was wrong. It all begs the question - why does someone like Mr. Davis not seek out a good Eastern Catholic parish? Most Catholics are oblivious about Eastern options. That might require moving (I have been in Byzantine parishes in five different states and understand the quality of worship is uneven), but it keeps one Catholic with all the beauty and tradition of Orthodoxy.

"The Protestants rejected the papacy, and in due course, rejected the Real Presence and the prerogatives of Our Lady; some even came to reject the Incarnation. The conceptual path from Lutheranism to Calvinism to Unitarianism to atheism is not difficult to trace." You go on to describe how despite the rejection of the papacy, etc., the Orthodox have not gone the way of erstwhile Protestants. I think it is precisely because the Orthodox DO reverence our common Mother, Mary. (I have something coming out soon at Catholic Exchange on that issue.)