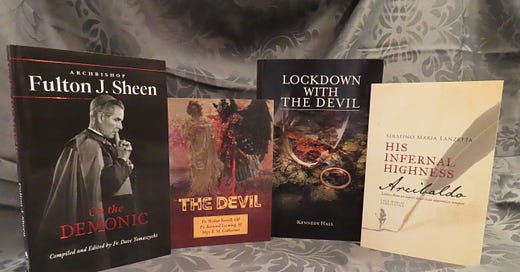

The usual Weekly Roundup is suspended until my return from the pilgrimage I’m helping to lead in Greece & Turkey. Instead, we’ll spend time today with some recent books that have caught my attention and might deserve yours once you hear about them.

Before we get to the books, a periodic reminder:

Preparing the content at Tradition & Sanity is a major part…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.