Building the Mystical City of God from Womb and Hearth: St. Thomas on Christian Marriage (Part 2)

Offspring and multiplied friendships promote the “more divine” common good

Note to all readers

Tradition & Sanity has multiple purposes. Among them is the identification of contemporary errors, together with a presentation of the profound authentic and traditional Catholic teaching. That is what we are doing, for example, in this short series on marriage.

It truly requires a lot of time to work on these posts, to select appropriate images to illustrate them, and to record the voiceover. Although I have many irons in the fire, Tradition & Sanity is the one I’m devoting the most hours to each week.

Yet the past month has seen a plateau in new paid subscriptions for this Substack. We are always growing in readers (indeed, we are getting close to 10,000 readers, and still at #20 worldwide in the Faith & Spirituality category), but the support base has not kept up with the free subscribers. Therefore…

Dear Readers:

If you value the content you find here, please take out a paid subscription!

If you are already subscribed, consider giving a subscription to a friend, relative, or cleric you know:

And if you would simply like to show your support on an ad hoc basis:

Now back to this Thursday’s public post.

We saw in our last post that St. Thomas Aquinas’s view of Christian marriage is both lofty and realistic: he appreciates its sacred signification but he also defends its honest-to-goodness physicality; for him, sexuality is not dirty, as it was for the Manichaeans, but part of God’s good creation—affected by the Fall, to be sure, but still inherently good, beneficial, and holy when exercised within the bounds of a Christian sacramental life.

The dignity of building up earthly & heavenly cities

Today I would like to go more extensively into the good of offspring (proles). While the word “offspring” has perhaps a more technical or colder feel in English than “children,” I think it is a marvelous word in its etymology. It’s from the Old English ofspringan, “to spring from,” that is, to be born and descended from. It strongly emphasizes the link of parents and children, links in a chain going back centuries, millennia, to our first father and mother, Adam and Eve, at the head of the human race, naturally speaking, even as Christ and His Mother, the New Eve, stand at the head of a new humanity reformed in grace. Offspring receive blood, name, tradition, and inheritance, be it in land or livestock, libraries or legends.

According to St. Thomas, even as marriage replenishes and expands the human race (and since the human race is loved by God, this already is good!), it also supplies new members for the Church. Socially, and on the natural plane, marriage is given “as a remedy…against the decrease in numbers that results from death.” On the supernatural plane, it has the privilege of “bringing into being the recipients who approach the sacraments” (ST III.65.1, corp.; ad 3).

Since the people of the faithful (populum fidelium) were to be perpetuated even to the end of the world, it was necessary that this be done by generation, through which also the human race is perpetuated. Now human generation is ordered to several ends: the continuation of the species; the securing of some political good, such as the preservation of the people in some civic body; it is, moreover, ordered to the perpetuity of the Church, which consists in the assembly of the faithful (fidelium collectione). (ScG IV.78)

The sacrament equips and obliges husband and wife to bring back to God, through Christ and his Church, the gift of children they receive from God. Rather strikingly, at one point Aquinas says: “The uppermost good of marriage is offspring brought up for the worship of God (proles ad cultum Dei educanda)” (Sent. IV.39.1.1). The married, in a way properly theirs, help build up the human race into the Mystical Body of Christ, the true goal of humanity.

When treating of the sacraments of the New Law, St. Thomas makes a distinction between agents and recipients in “hierarchical actions,” and notes the obvious but still wonderful truth that without suitable recipients, there could be no giving of sacraments by their agents (see ST III.65.1 ad 3). We tend to pass over too quickly the enormous privilege granted to Christian men and women of, as the saint puts it, “bringing into being the recipients who approach the sacraments” (ibid.), and so, assisting Christ in providing spiritual nourishment for His people. As Newman once said, in a pugnaciously anticlerical mood, that the Church would look rather foolish without the laity, so we might say the sacramental system would look rather foolish without people to receive the sacraments. If we have a sufficiently lofty view of the sacraments as divine and divinizing actions, we will be quite impressed that we can have anything at all to do with making them possible.

In a comment that homeschoolers will particularly appreciate, Thomas says that upbringing (educatio) has to take into account, of course, the bodily nourishment of one’s children, but it has much more to do with “nourishment of the soul (nutrimentum animae).”1

Profound link between marriage & the common good

Given the foregoing, there is a strong link between marriage and the common good (bonum commune).2 In the Scriptum, when treating of the proper order in which to enumerate the sacraments, Thomas voices the argument that marriage and holy orders have a certain precedence over the other five because they directly serve the common good, which is more divine than the good of the person3—and, rather than simply disagreeing, he twice observes that individuals must be perfected before a community can be perfected, since the latter is constituted out of the former.4 This seems to grant a qualified primacy to that which perfects a community as such, since the common good, as Aristotle says (approvingly quoted by Aquinas), is something more divine than the good of the individual.

In fact, St. Thomas holds that “among natural acts, generation alone is ordered to the common good.”5 That is, of all the works we men and women do by nature for the good of our nature, only begetting and bearing children is in and of itself aimed at the good shared by many, making generation godlike (as indeed, from divine revelation, we already know that it is, for the source of all earthly generation lies in the mystery of the eternal generation of the Divine Persons, who simply are the common good of the universe). Thomas underlines the excellence of the good in question when he writes: “Just as the preservation of the bodily nature of one individual is a true good (vere bonum), so, too, is the preservation of the nature of the human species a very great good (quoddam bonum excellens)” (ST II–II.153.2). In one of many lists he draws up of the effects of marriage, Aquinas enumerates “the good of children, the restraining of concupiscence, and the multiplication of friendship” (Sent. IV.40.4, arg. 5). Note that two out of three are social goods, diffusions of the good.

For St. Thomas, the uppermost reality at work in and displayed by the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ is the burning charity of His Heart.6 This being so, the statement that “the conjoining of Christ to the Church, which marriage signifies, is perfected by charity” (Sent. IV.31.1.2, arg. 2) amounts to saying that this state of life, if lived as St. Paul instructs us to live it in Ephesians 5, both objectively assimilates the spouses to that supreme mystery of redemptive love and subjectively fills them with it. This is implied in Thomas’s statement that grace is the reality contained by the sacrament, its res contenta to use the technical term (Sent. IV.26.2.3).

Unfortunately for us, he did not explicate this truth as much as he might have done; still greater mysteries commanded his attention — the sovereign mystery of the Eucharist most of all. And with good reason: the Eucharist, says Thomas again and again, really contains the very One who suffered for us, and thus brings to the communicant the very source and goal of charity. For example, in one place he says: “Marriage is ordained to the common good, in a bodily way. But the common spiritual good of the entire Church is contained substantially in the sacrament itself of the Eucharist” (ST III.65.3, arg. 1).

Expanding on that idea, another passage adds: “the Eucharist is the sacrament of the Passion of Christ inasmuch as man is perfected in union with the Christ who suffered (in unione ad Christum passum). Thus the Eucharist is called “the sacrament of charity, which is the bond of perfection” (ST III.73.3, ad 3). In an especially pithy line he remarks: “The Eucharist is called the sacrament of charity—expressive of Christ’s, and effective of ours (sacramentum caritatis Christi expressivum, et nostrae factivum)” (Sent. IV.8.2.2.3, ad 5).

What Christian marriage symbolizes is truly present in the Eucharist; it is this sacrament that brings about, and ever deepens, the “spiritual marriage” (as Thomas expressly calls it) in which eternal life consists: the indissoluble unity of the Bride and the Bridegroom, of the members with their Head.

Brief digression on the spiritual marriage

Real marriage affords us the experiential basis for the analogy of spiritual marriage, which plays such an enormous role in the history of Christian spirituality and even ecclesiology, as I will show in a moment.

Aquinas appeals many times, directly or indirectly, to the idea of matrimonium spirituale. Usually he is speaking of the soul’s spiritual union with God, or the Church’s union with Christ. Typical examples would be: “in the state of the Church militant, a spiritual marriage is contracted with Christ by faith” (Sent. IV.49.4.1, arg. 4);“in the justification of sinners man contracts a kind of spiritual marriage with God, as is written in Hosea 2:19: ‘I will espouse thee to me in righteousness’” (De veritate 28.3, sc 4); “through charity, the soul is united to God as a spouse according to a kind of spiritual marriage” (De caritate 12, arg. 24); “in its mystical meaning, the mother of Jesus, the Blessed Virgin, is present in spiritual marriages as the one who arranges the marriage, because it is through her intercession that one is joined to Christ through grace” (Super Ioan. 2, lec. 1, no. 343); “Christ espoused the Church by His Incarnation and Passion: wherefore this is foreshadowed in the words ‘A bridegroom of blood thou art to me’ (Ex. 4:25)” (Sent. IV.49.4.4, sc 2).

Strikingly, Thomas also uses such language when speaking about the relationship of a bishop, or the pope, or even a parochial priest, to his local church. The most impressive of these texts is from the Contra impugnantes:

The spouse of the Church is Christ…. He, by His Church, begets children to bear His name. Others who are called spouses are [in reality] servants of the Bridegroom who co-operate with him exteriorly in this work of spiritual generation…. They are termed spouses because they stand in the place of the true Spouse. Hence, the Pope, who is the vicegerent of Christ for the whole Church, is called the spouse of the universal Church; in like manner a bishop is termed the spouse of his diocese, and a priest of his parish. Thus, Christ, the Pope, the bishops, and the priests are but the one spouse of the Church.7

Having this insight, we can say with strict accuracy that a pope who governs badly, who puts private agendas and vendettas before the common good and who fails to love and nurture the faithful as he is bound to do, is nothing other than an abusive husband to the Church, his bride. The same holds for bad bishops and bad priests: all blaspheme against Christ the Bridegroom as they abuse His bride on earth. We know, thanks be to God, that this will never happen in the kingdom of heaven, where Christ alone is the Bridegroom who has the Bride all to Himself, so to speak, indissolubly and for ever; where the wedding feast is never over, and the wine of love never runs out. To this paradise of bliss may He one day bring us! Amen.

How marriage is like and unlike the other sacraments

Thus, while the sacrament of marriage signifies the highest mystery, it does not, unlike the other sacraments, effect precisely what it signifies.8 That is, it does not actually bring about the union of Christ and the Church; rather, it is derived from that preexistent union and points to it as the reality signified but not contained (the res significata non contenta).

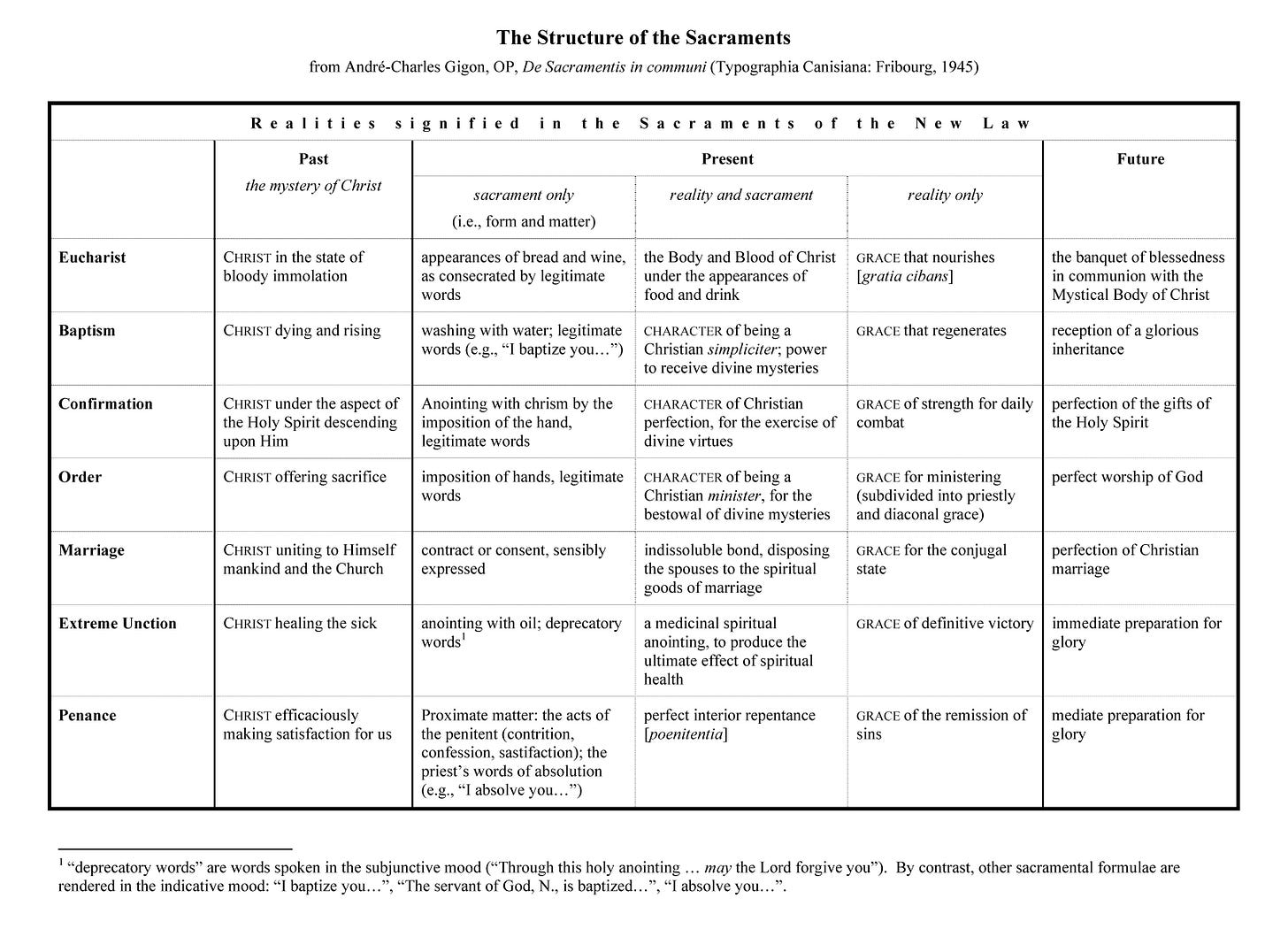

Here we have to harness up and do some technical climbing. All the sacraments signify grace as the res tantum (the innermost reality of the sacrament), but in order to do so, they must first signify some determinate effect as the res et sacramentum, which then serves as the sign of that grace. The external visible sign that we experience, the sacramentum tantum, is constituted by the conjunction of the sacrament’s matter and form.

This trio of terms points to three inseparable aspects of a sacrament: the sacramentum tantum is the immediate sensible sign; the res et sacramentum is the reality given to us under that sign, which is itself the sign of a further and ultimate reality, the res tantum, to which the sacrament grants access. Examples will bring this out very clearly.

The sacramentum tantum of the Eucharist — the words of consecration spoken over the bread and wine — signifies and brings about the real Body of Christ, which in turn signifies and brings about the unity of the Mystical Body of Christ.

The sacramentum tantum of baptism, that is, the baptismal formula spoken while immersing the candidate in water or pouring water over his head, signifies and brings about the washing away of sin and the Christian’s spiritual death and resurrection.

The sacramentum tantum of penance, that is, the words of absolution spoken “over” the penitent’s self-accusation, signifies and brings about absolution from sin, etc.

In contrast, the sacramentum tantum of marriage signifies but does not bring about the union of Christ and the Church as such; rather, it brings about an indissoluble bond or nexus between spouses that is like that greater union, but not identical to it. Among other things, the union of Christ and the Church is eternal, whereas that of human spouses is temporal and temporary, and however spouses are united in heaven, it is not a connection such as they had on earth, as the response of Our Lord to the Sadduccees proves.9

The Dominican theologian André-Charles Gigon maintains that the mutual in-the-present consent of a marriageable man and woman is the sacramentum tantum; the indissoluble bond between them is the res et sacramentum; and the matrimonial grace for living their state in holiness is the res tantum.10 Therefore, marriage does effect what it signifies, if the effect be understood as the grace to live the spousal union in holiness— which is itself a sign of something further, Christ’s union with the Church. This Aquinas openly says in the Summa contra Gentiles:

Because the sacraments effect what they symbolize, we must believe that this sacrament confers upon the bridal pair the grace by which they may reach (or relate to, or pertain to: pertineant) the union of Christ and the Church, which is most necessary for them, so that they may seek fleshly and earthly things in such a way as not to be disjoined from Christ and the Church. (ScG IV.78)

What I find fascinating about this formulation is that Aquinas realistically recognizes that family life in this world requires “seeking fleshly and earthly things”: that simply isn’t avoidable. You can’t have a family without the nuptial act; you can’t have healthy parents and children without food, drink, shelter, and resources; there must be a domestic economy, money coming in and going out, and so forth. This sacramental life is material through and through. So the grace that is needed is precisely a grace to live amidst the changing things of this world while remaining united in soul to the Lord and His Mystical Body, where the ultimate meaning of all that we do here below is to be found and will be given us in full in the world to come. Matrimony, you might say, is the sacrament par excellence of divinizing the human, supernaturalizing the natural, fructifying human fruitfulness, purifying the earthly pilgrimage, sanctifying earthly sufferings. Its humble circumstances sometimes make us forget the almighty power displayed in its working!

Always one to be more daring than other Thomist theologians, Matthias Scheeben maintains that marriage in a way does build up the union of Christ and the Church; he says it does so by multiplying the Church’s members, in order that Christ might be united to more souls.11 In a sense, then, marriage augments that union mediately and indirectly; in itself, however, the sacrament is perfected prior to that augmentation occurring, and the addition of members to the Mystical Body makes us part of the preexisting Church of the blessed united to its Head, even as our prayers do not move God to new divine action but rather make us receptive to that which the unchanging God is prepared to bestow on those who ask, seek, and knock.

Marriage’s unique sacramental profile

What is most special about Christian marriage, then, is its unique and proper signification: “since wedlock (conjugium) is a sacrament, it is a sacred sign, and of a sacred thing,”12 writes Thomas, namely, “the mystery of the conjoining of Christ and the Church” (Sent. IV.26.2.2), “which is made in the freedom of love (secundum libertatem amoris).”13 No other sacrament in fact signifies this ultimate mystery of our communion with God in Christ, and since that is our destiny and our happiness, marriage has a particular symbolic privilege in regard to the ultimate end of human life, even if it is by no means necessary to choose it in order to attain that end. Put simply: without marriage God would not have a language in which to communicate to us what He intends for us. Put more provocatively: God made marriage in order to have a language in which to communicate with us. (I plan to speak more about this in a future post.)

So important is marriage’s sign-value that Thomas can say:

In every way, ‘sacrament’ is the foremost of the three goods of marriage, for it pertains to marriage insofar as it is a sacrament of grace, whereas the other two [goods, viz., offspring and fidelity] pertain to it insofar as it is an office of nature—and the perfection of grace is nobler than the perfection of nature. (Sent. IV.31.1.3, sc 2).

Thomas sees the sacramentality of marriage as a perfection that God introduces from without, so to speak, rather than something that wells up immanently from human nature, the way offspring and fidelity do.14 Thus, to the question “What is most essential to marriage?” there must be two answers: one from the vantage of its natural function, namely to promote the human race by “increasing and multiplying,” and the other from the vantage of its supernatural function, which emanates from and concerns itself with the nuptial union of Christ and the Church.

Of course, Thomas always says that if by offspring or fidelity one means not the thing itself but the intention thereof, then either of these is more essential to marriage than sacramentality, inasmuch as the nature of a thing precedes its elevation by grace. If there is no man, there is no saint; so too, if there is no permanent sexual relationship ordered to offspring, there is no indissoluble grace-giving bond (Sent. IV.33.1.1). Thomas says:

The [final] cause of marriage per se is that to which marriage is of itself ordered, namely, the procreation of children, and the avoidance of fornication… [but] that which has one end per se and principally can [also] have many per se secondary ends, as well as an infinity of per accidens ends. (Sent. IV.30.1.3; ad 1).

A moment ago, we saw that for the Angelic Doctor, matrimony is “a sacred sign of a sacred thing, namely, the mystery of the conjoining of Christ and the Church.” Indeed, it is this “marriage” of God and man signified by human marriage that captivates St. Thomas the mystical theologian most of all. In company with writers of the Eastern and Western traditions who preceded him, Thomas often utilizes marriage as a metaphor or image of God’s dealings with His people in covenant history, of Christ’s one-flesh relationship with the Church, His Body, and of the individual soul’s intimate union with the Lord. In these respects he is a willing exponent of the mystery revealed in Sacred Scripture: the “good news” of God’s love for us and of our being caught up in that love, a “mutual indwelling” (mutua inhaesio, ST I–II.28.2) that is likened in many revealed texts to the relationship of husband and wife—above all, in the Song of Songs, Psalm 44,15 the prophets Hosea, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, the Letter to Ephesians, and the Book of Revelation.16

Such texts on “spiritual marriage” are regularly cited by Thomas, not as mere ornamentation but as authoritative premises and as doorways that lead the reader or listener back into the inspired word, where he may nourish himself in lectio divina, for the personal appropriation of revealed truth.17 After all, it was no frivolous decision when Aquinas, in his magnificent divisio textus of Scripture,18 declared the point of arrival for the whole inspired word to be our spiritual marriage with the Lord, and doubly so: in the Old Testament the peak is the Song of Songs (which treats of “the virtues of the cleansed soul, whereby a man, with worldly cares altogether behind him, delights in the contemplation of wisdom alone”),19 while in the New Testament the peak is the Book of Revelation: after learning of the beginning and the progress of the Church, we come to “the culmination of the Church, with which the Apocalypse concludes the contents of the whole of Scripture—until which time the Bride is in the bridal chamber of Jesus Christ awaiting her participation in the life of glory; to which may Jesus Christ himself lead us, who is blessed forever.”20

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you.

In Super I Cor. 7, lec. 1. See Sent. IV.31.2.3, ad 1; Sent. IV.33.1.2, ad 5; Sent. IV.39.1.2; ScG III.122; ScG IV.58.

For the definitive treatment of this central concept in the theological vision of St. Thomas, see Charles De Koninck, The Primacy of the Common Good, in The Writings of Charles De Koninck,Volume 2, ed. Ralph McInerny (South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009). For discussions that have many points of contact with the present inquiry, see Michael Waldstein, “The Common Good in St.Thomas and John Paul II,” Nova et Vetera 3 (2005): 569–78, and idem,“Children as the Common Good of Marriage,” Nova et Vetera 7 (2009): 697–709.

Sent. IV.2.1.3, arg. 3; cf. Sent. IV.26.1.2, arg. 3; Sent. IV.31.1.1, arg. 1.

Sent. IV.2.1.3, corp.; ad 3.

ScG III, ch. 123, Ulterius.

See, e.g., ST III.47.2, ad 1 & ad 3; q. 48, aa. 2–3.

Part II, ch. 3, ad 22.

See In IV Sent., d., 26.2, arg. 4 (“marriage does not effect the union of Christ and the Church that it signifies”) and ad 4. In contrast, for example, the pouring of water in baptism accompanied by the words symbolizes washing from sin and dying and rising in Christ—and it does wash from sin and make one die to sin and rise spiritually with Christ (see Sent. IV.27.1.2, qa. 1). At Sent. IV.27.1.2, qa. 2; cf. ibid., qa. 4,Aquinas states:“The expression of words [in giving consent] stands to marriage as the exterior washing stands to baptism.”

See Matthew 22:23–33; Mark 12:18–27; Luke 20:27–39.

See André-Charles Gigon, O.P., De Sacramentis in communi (Fribourg: Typographia Canisiana, 1945).

See Matthias Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, trans. Cyril Vollert, S.J. (St. Louis: B. Herder, 1946), ch. 21,“Christian Matrimony.”

Sent. IV.26, prologue. It is a distinct sacrament because it uniquely signifies a determinate sacred thing (Sent. IV.31.1.3, ad 2).

The full statement: “marriage signifies the conjoining of Christ to the Church, which is made in the freedom of love. Therefore it cannot happen by coerced consent” (Sent. IV.29.3, qa. 1, sc 2).

See Marc Ouellet, Divine Likeness: Toward a Trinitarian Anthropology of the Family (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2006), 125–26.

Super Ps. 44 is one of Aquinas’s most ample treatments of the marriage between Christ and the Church. He says at the start of his remarks: “The content of this psalm and that of the book called the Song of Songs is the very same (eadem est materia hujus Psalmi et libri qui dicitur Cantica Canticorum).”

For an excellent example of a text in which Thomas expressly refers to a number of these texts to refute a view of some of his contemporaries on why having had more than one wife invalidates a man for holy orders, see Sent. IV.27.3.1.3.

One who researches St. Thomas’s citations of the Song of Songs will see the extent to which the traditional allegorical/mystical exegesis influences his interpretation and applications. There is enough material in the master’s writings to permit a speculative reconstruction of a Thomistic Song commentary, or at least an ample prologue to such a commentary.

The De partitione sacrae scripturae of the second Principium, on the text “Hic est liber mandatorum Dei.” The two Principia or inaugural lectures are printed (albeit in reverse order) in the Opuscula theologica, vol. I, ed. R.A. Verardo (Turin/Rome: Marietti, 1953), 435–43; see nn. 1203–8 for the divisio textus of Scripture. On the importance of this divisio, see my forthcoming book Anatomy of Transcendence: Mental Excess and Rapture in the Thought and Life of Thomas Aquinas (Emmaus Academic, 2025).

That middle phrase (taken from the De partitione sacrae scripturae, n. 1207 in the Marietti ed.) is difficult to translate: In tertio gradu sunt virtutes purgati animi, quibus homo, saeculi curis penitus calcatis, in sola sapientiae contemplatione delectatur; et quantum ad hoc sunt Cantica. The description is that of the highest peak of holiness according to ST I–II.61.5, where the state is also called “a perpetual covenant with the Divine Mind.”

Tertio ecclesiae terminum; in quo totius Sacrae Scripturae continentiam Apocalypsis conclu- dit, quousque Sponsa in thalamum Iesu Christi ad vitam gloriosam participandam; ad quam nos perducat ipse Iesus Christus, benedictus in saecula saeculorum (from the De partitione sacrae scripturae, n. 1208 in the Marietti ed.).

I absolutely love the bottom left detail of the Barna Da Siena painting, with (Catherine? Mary? The Church?) pounding on the devil with a hammer--take THAT, diablo!