Preliminary note

After I sent out last Friday’s post, a reader send me a little note, full of perplexity:

Please forgive me if I'm reading the following sentence incorrectly: “As faithful believers, we try to observe and to do not what the one who sits on the chair of Peter says.” As a faithful believer—indeed, a traditionalist—am I meant to listen to the pope and then try not to do what he he says?”

Crumbs. The “not” was not supposed to be there! It resulted from one too many rewrites. The sentence should have read:

As faithful believers, we try to observe and to do what the one who sits on the chair of Peter says.

I read all my articles more than once, but typos still escape my eye (as they do everyone’s). My apologies to anyone who was puzzled or, worse, offended by the mistake!

Now to the main feature.

Codes of honor

When I was growing up, it seemed to me as if no one ever “dressed up” except for work or church. Nowadays, precious few people dress up for either of those. It seems that an all-inclusive slobitude prevails: dressing down to the lowest common denominator — some minimal covering of body parts, as comfortable and undemanding as possible. With Sebastian Morello, I lament that women now step out into the street in what used to be considered underwear (leggings or tights and crop-tops), or in pyjamas with fluffy slippers. Men are scarcely any better.

The all-boys’ Benedictine high school that I attended in New Jersey used to have a blazer-and-tie dress code, but not too long before I matriculated, that wise provision had been thrown aside in a moment of foolish aggiornamento. My father worked for an accounting firm in New York City and never left home without a jacket and tie, but I remember everyone in my family thinking me odd because, by the time I’d reached the last two years of high school, I had come to enjoy wearing button-down shirts and ties, and did so just about all the time, even on weekends, unless I was mowing the grass.

My favorite pastime was not mowing the grass; it was sitting quietly in a loudly plaid-patterned reclining chair in the corner of my bedroom and reading stacks of books. I still remember the springy motion of the chair, the frayed bits of fabric here and there, the lamp right next to me with the slidable dimmer on the floor for foot activation.

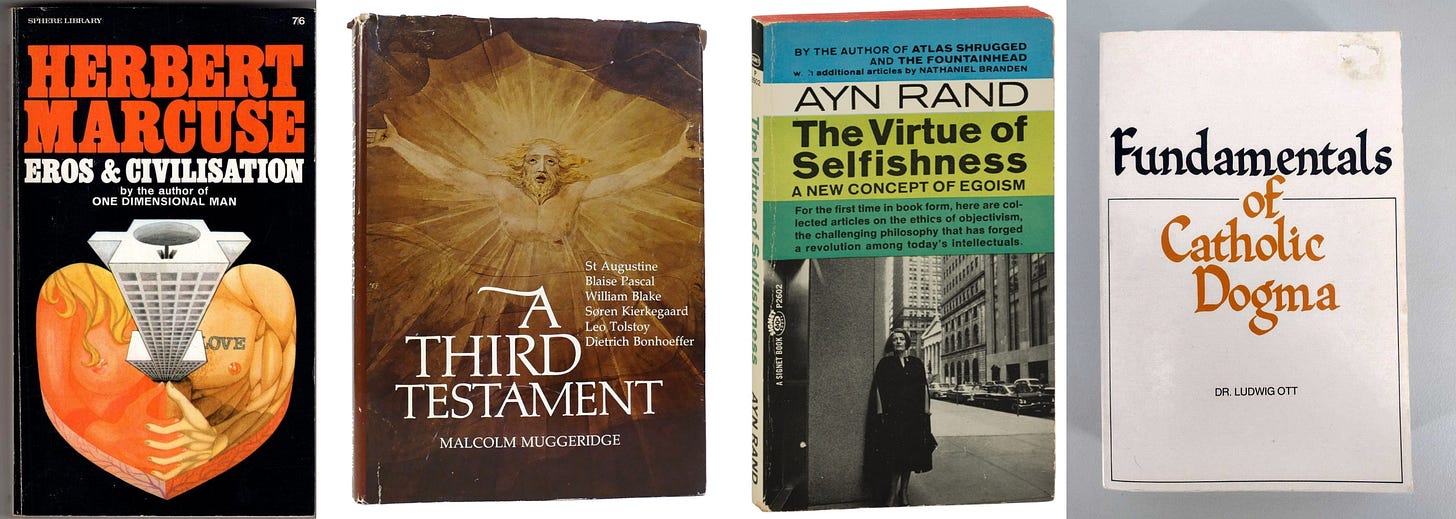

Week by week, I’d take out the most incompatible array of books from the monastic library of my school: the backpack stash might include, in no particular order, Herbert Marcuse, Ayn Rand, Malcolm Muggeridge, and Ludwig Ott. I read and wrote modernist poetry while fiddling with my pipe. In one particularly uppety (and, in retrospect, quite laughable) attempt to mimic Eliot’s multilingual The Wasteland, I wrote a poem about “Astarte alla Fruchtbarkeit.”

In retrospect, I can see that all this was a form of countercultural rebellion, even if I wouldn’t have put it that way. I had read enough serious books to convince me that the Western world was in a state of irreversible and execrable decline, and I wasn’t about to contribute to it by surrendering to its decline, although I had no actual idea of exactly what the decline consisted in or exactly what the solution might be.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.