“Deliver us, we beseech Thee, O Lord, from all evils past, present, and to come”

A Mighty Prayer in the Roman Rite

As St. Augustine and St. Gregory bear witness, it was never the custom in the Roman church for the people to say the entire Lord’s Prayer; the celebrant alone does so, and the people respond at the end: “Sed libera nos a malo.”1 The priest says “Amen” and then moves immediately into the “embolism.”

Taking the paten between his first and second fingers, he prays:

Líbera nos, quæsumus, Dómine, ab ómnibus malis, prætéritis, præséntibus, et futúris: et intercedénte beáta et gloriósa semper Vírgine Dei Genitríce María, cum beátis Apóstolis tuis Petro et Paulo, atque Andréa, et ómnibus anctis, + da propítius pacem in diébus nostris: ut ope misericórdiæ tuæ adjúti, et a peccáto simus semper líberi, et ab omni perturbatióne secúri, [he uncovers the chalice, genuflects, takes the Host and breaking it down the middle over the chalice says:] per eúndem Dóminum nostrum Jesum Christum Fílium tuum, [he breaks off a Particle from the Host], qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitáte Spíritus Sancti Deus, [then aloud] per ómni sæcula sæculorum.

Deliver us, we beseech Thee, O Lord, from all evils, past, present and to come, and by the intercession of the blessed and glorious ever Virgin Mary, Mother of God, together with Thy blessed apostles Peter and Paul, and Andrew, and all the Saints, + mercifully grant peace in our days, that through the bounteous help of Thy mercy we may be always free from sin, and safe from all disquiet. Through the same Jesus Christ, Thy Son our Lord, Who is God living and reigning with Thee in the unity of the Holy Ghost, world without end.

To which all reply: Amen.

Michael Fiedrowicz comments as follows:

The last petition of the Our Father is continued into a quietly spoken embolism (“insertion”) that asks once more before Communion for deliverance from evil of any kind (Libera nos ab omnibus malis)—those consequences of sin having a lasting effect (praeteritis), present afflictions (praesentibus), or impending temptations (et futuris)—and, as a prayer for peace (da propitius pacem in diebus nostris—simultaneously a continuation of the diesque nostros in tua pace disponas from the Hanc igitur of the Canon), leads over to the subsequent ceremonies of peace (greeting of peace: Pax Domini sit semper vobiscum; Agnus Dei . . . dona nobis pacem; the priest’s preparation for Communion: Domine Jesu Christe).

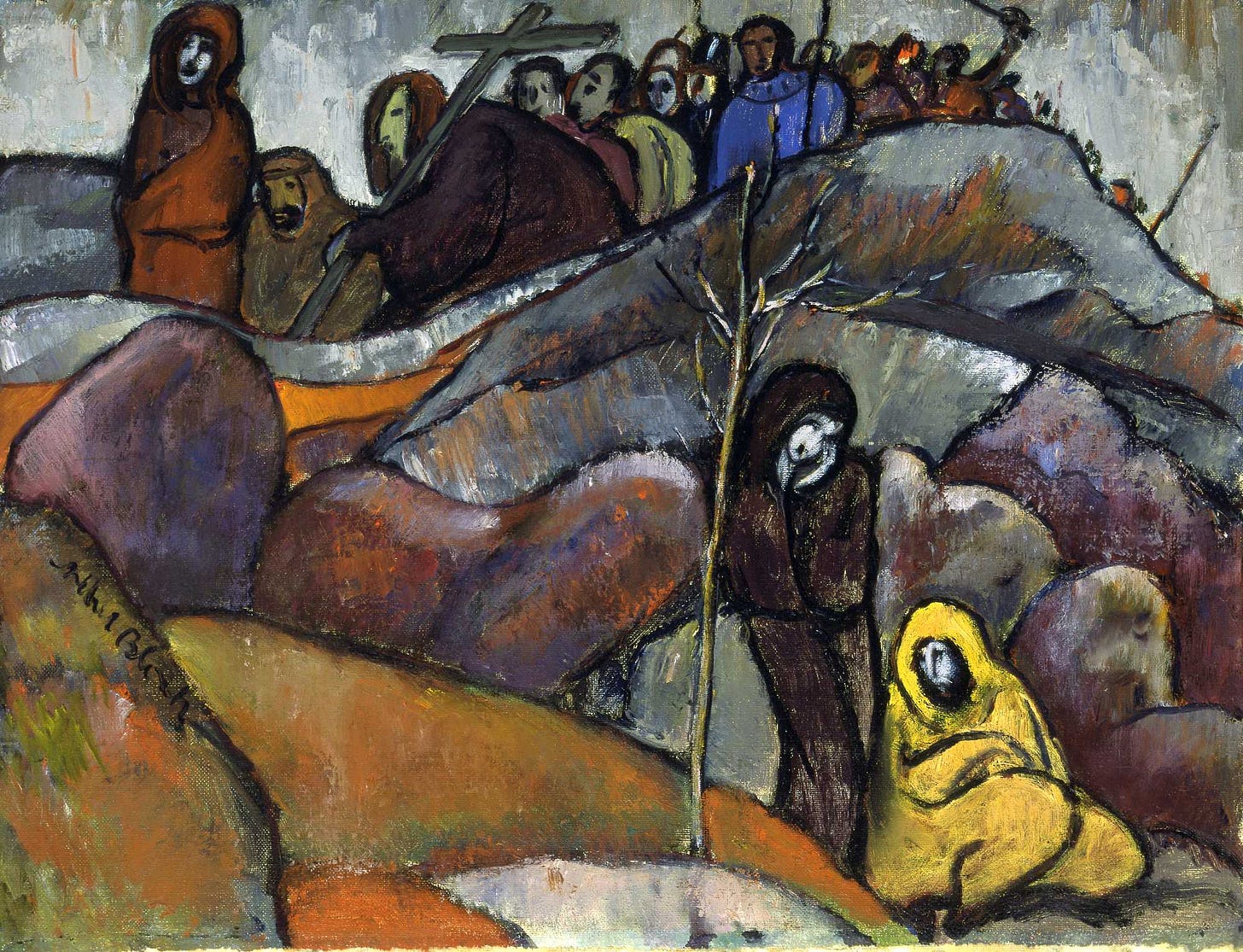

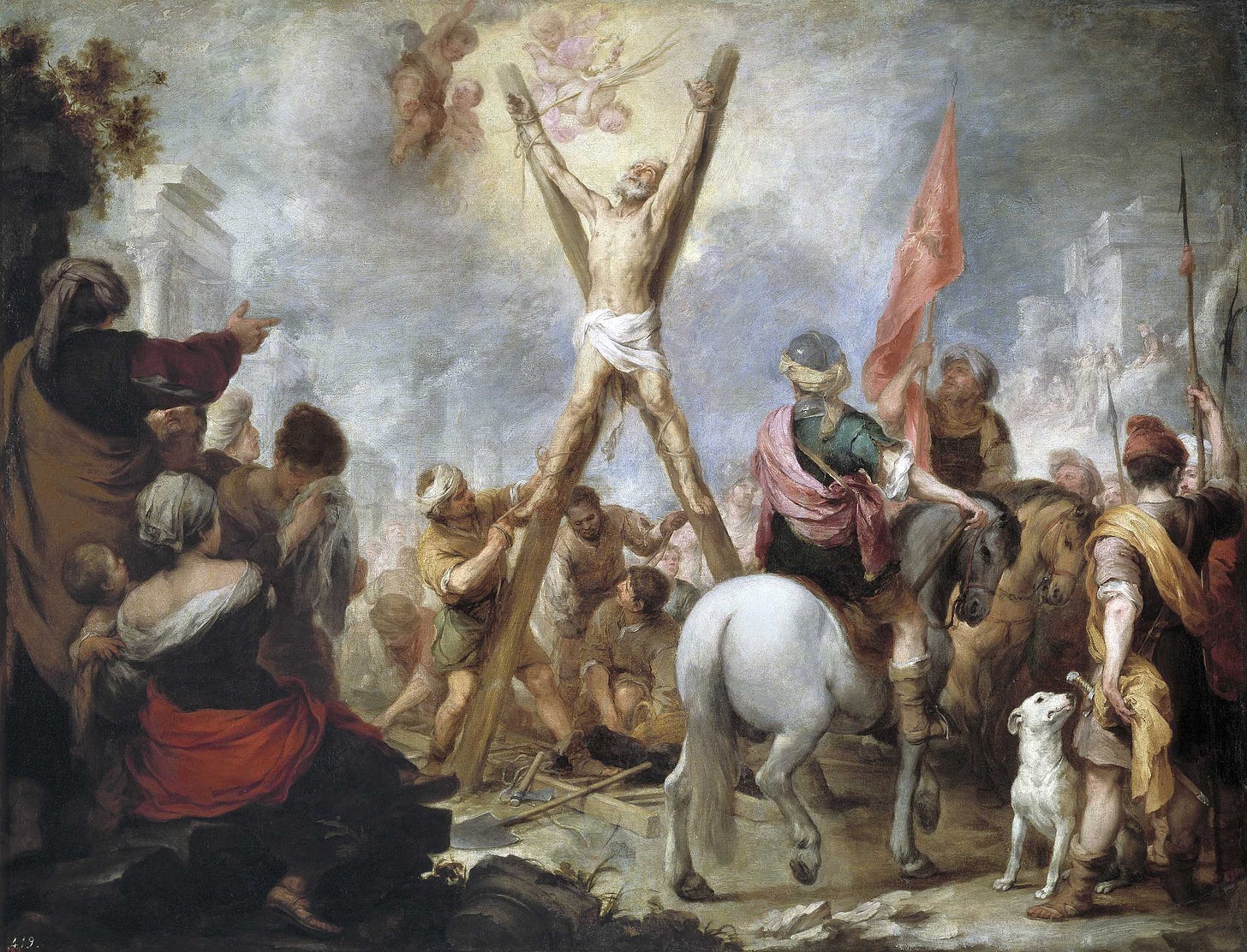

As heavenly intercessors, Mary as well as both of the founders of the Church in Rome, Peter and Paul, are invoked, but also St Andrew, who, as the brother of St Peter, was especially venerated in Rome already from the time of the fifth century. Since the Byzantine Church traces her founding back to this Apostle, his being named together with the Princes of the Apostles is also a sign of communion with the Eastern Church.

During this prayer the priest holds the paten, placed vertically over the purificator outside of the corporal, in order to cross himself with the paten at the words da propitius pacem as a sign that Christ established this peace on the Cross (cf. Col 1:20). After he has reverently kissed the paten, as a holy vessel upon which the Body of Christ will rest, he slides the Host, which has been lying on the corporal up to this point, onto the paten, which now takes its place in front of the chalice.

During the closing formula of the embolism Per eundem Dominum nostrum Jesum Christum, etc., the priest breaks the host above the chalice in order to indicate that this [vessel] contains the Blood that poured out of Christ’s sacrificed Body on the Cross, especially from His opened side (cf. Jn 19:34).2

Fiedrowicz also notes why the prayer is said silently:

The placement of this prayer in the section of the Mass that represents the Passion of Christ before His Resurrection (symbolized in the subsequent commingling of the Body and Blood of Christ) made the quiet praying of the embolism seem more appropriate, as during the Canon, around the turn of the millennium.3

This prayer has always been one of my favorites in the Roman Rite. I memorized it and always pray it silently along with the priest. Can there possibly be a better, more necessary, more urgent petition in the entire world than this one (at least as regards the removal of impediments to holiness and happiness): “Deliver us, we beseech Thee, O Lord, from all evils, past, present, and to come”?

There are so many evils that haunt us from the past. We want to be free of them, rid of them, healed from them, forgiven of them; we want others we have harmed to be healed. These past evils, though gone, still rankle and stalk and shame us, and we struggle to overcome the memory, if no longer the temptation. We beg the Lord: “Deliver us from all past evils!”

Many are the evils to which we are subject in the present time: it could be poor health, a long-lasting illness, troubles in the immediate family, difficult relatives, a falling-out with a friend, confusion of mind, desolation of soul, persecution at the hands of civil or ecclesiastical leaders, lack of work or ill-suited work, financial worries, natural disasters—the list is practically endless.

As for the future, who can know but God alone the innumerable waves of evils that may be headed our way—enough, perhaps, to make us go mad or fall into despair if we somehow knew them all at once, instead of facing them day by day with just enough grace to overcome them?

Fr. Nicholas Gihr in his classic commentary on the Mass writes:

Why do we dwell so long at the petition for deliverance from all and every evil? Because this earth on which we, as exiled children of Eve, are still sojourning, is a land of thistles and thorns: who could possibly enumerate all the spiritual and corporal evils that sprout from the poisonous root of sin? The life of mortal man overflows with hardships and miseries, with sorrows and sicknesses, with cares and disquietudes, with dangers and temptations, with fear and anxiety, with grief and mourning. Truly, very many are the afflictions of the just; but in all their necessities the Lord hears and delivers them (Ps. 33, 20). Assuredly, “we are now the sons of God; and it hath not yet appeared what we shall be” (1 John 3, 2). The happiness, the dignity, the sublimity and glory of our adoption as children of God are not yet perfect here below, but only in a state of development and enveloped in the darkness of lowliness. Hence as long as we remain on earth, encompassed with infirmity and subject to suffering, to spiritual combat and labor, it is ever necessary for us to pray for deliverance from all evils, past, present and to come.

Of past evils, sins especially often continue to abide in their painful consequences, in their unhappy results and fruits—the latter, therefore, should be totally removed and obviated. In the present we are pressed down by evils from within and without, from all sides—and from these we wish to be delivered. The future is frequently enveloped in darkness, and in its bosom conceals a host of threatening evils—and from these we would beg to be spared.

The infinitely holy and just God oftentimes permits painful visitations, sufferings and tribulations to befall us, not merely for our trial and purification from all inordinate attachment to the world, but also as a chastisement for our sins, imperfections and infidelities; therefore, we earnestly beseech the Lord not to chastise us in His wrath and indignation (Ps. 6, 2), but to regard us with the eyes of His favor and be propitious to us (propitius), and to give us true peace in our days (pacem in diebus nostris).

We here pray in the first place for interior peace of soul, which consists in this, that by the powerful assistance of the Divine Mercy we may ever keep ourselves free from sin and at a distance from it, whereby we shall persevere in the blessed love and friendship of God and rejoice in the sweet consolations of His grace.

Afterward for exterior peace of life, which consists in this, that by God’s help and merciful protection we may be ever secure from all disturbances, disquietudes, disorders, molestations, persecutions, by which in our frailty we are easily drawn from the right path of salvation and led into evil. If the days of our life are not darkened by fears from within and combats from without (2 Cor. 7, 5), that is, by the bitterness of sin and the misery of contention, then we enjoy the blessings of interior and exterior peace, whereby we taste already beforehand some drops from the fountain of heavenly, eternal peace.

To obtain the inestimable gift of this desirable peace the more easily and in greater abundance, we have recourse to the intercession “of the glorious Mary, ever Virgin, Mother of God, together with the blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and Andrew, and all the Saints.” For the sake of such intercessors, our supplications will be answered, and the superabundant riches of the divine mercy be imparted to us.4

Let us hear, too, from Dom Guéranger, who says in his succinct commentary on the Mass:

The priest, therefore, says, as if developing the last petition of the Lord’s Prayer: Libera nos, quaesumus, Domine, ab omnibus malis praeteritis, praesentibus et futuris. Yea, Lord, strengthen us, because our past evils have caused us to contract spiritual weakness, and we are as yet but convalescents. Deliver us from the temptations of which we are now being made the butt, and from the other afflictions which are weighing us down, as well as from the sins of which we may be guilty. In fine, preserve us from those evils which may be lurking for us in the future.

Et intercedente beata et gloriosa semper Virgine Dei Genitrice Maria, cum beatis Apostolis tuis Petro et Paulo, atque Andreae et omnibus sanctis. Holy Church, standing in need of intercessors, fails not to have recourse to the Blessed Virgin, as well as to the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul. But why is Saint Andrew alone, here added on to these? Simply because the Holy Roman Church has ever had a very special devotion to this Apostle.

Da propitius pacem in diebus nostris, ut ope misericordiae tuae adjuti, et a peccato simus semper liberi, et ab omni perturbatione securi. Give us, Lord, peace in these our days, so that aided by the help of Thy mercy, we may be delivered, in the first place, from all sin, and then be secured against all evil attacks that might surprise us unawares.

Such is this magnificent prayer of Peace, which is used by Holy Church for this special Mystery of Holy Mass.5

Lastly, a recent writer, Fr Cassian Koenemann, OSB, in his fine book The Grace of “Nothingness”: Navigating the Spiritual Life with Blessed Columba Marmion, develops another angle:

In keeping with Marmion’s liturgical interests and in accord with Saint Thérèse’s “little way,” I speculate he probably viewed the ascetical process within the context of this prayer: “Deliver us, we beseech Thee, O Lord, from all evils, past, present, and to come; and by the intercession of the blessed and glorious ever Virgin Mary, Mother of God, and of the holy Apostles, Peter and Paul, and of Andrew, and of all the Saints, mercifully grant peace in our days, that through the assistance of Thy mercy we may be always free from sin, and secure from all disturbance.”

While no one would deny the necessity of this prayer, which Marmion made during the very fraction of the Eucharist, many people fail to allow this prayer to have its full effect on a practical, subjective level. While Semipelagians do not deny the necessity of grace, they do construct obstacles to it. Those who obstruct the power of this august prayer are trying either to elevate or to liberate themselves—all in cooperation with God’s grace, in their minds—rather than make themselves “monuments to God’s mercy.” To follow spiritual childhood or to accept to be a monument to God’s mercy is to reverse completely the mentality of spiritual accomplishment. A Semipelagian simply refuses to be sanctified deeply because he is always trying to sanctify (or perfect) himself. Rather than accept his nothingness, he uses self-reliance to break free from it. In doing so, he refuses the liberation of allowing God to sanctify him at ever-deeper levels.6

These commentators have admirably illustrated numerous facets of this very rich prayer, handed down by tradition. Indeed, every notable liturgical writer across the centuries has commented on exactly this prayer. Here we see one of the immense benefits of adhering to the Church’s stable tradition. As Joseph Shaw points out, whole libraries have been written on the fixed prayers, antiphons, readings, etc., of the Roman Mass; we can choose a writer from any century and find ourselves right at home, for they dwelt in the same liturgical home we do, if we assist at the same Mass they did.

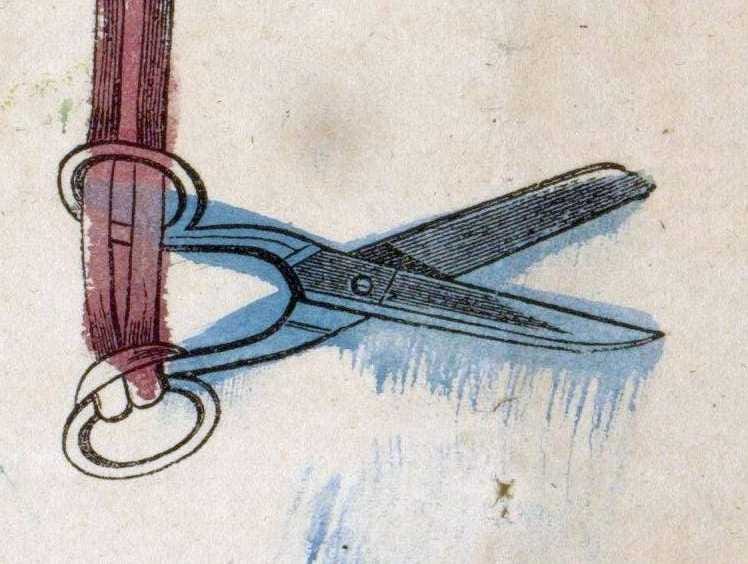

Since, like every other aspect of the liturgy, the embolism was dismantled and reconstructed by the Consilium into a form that bears only a generic resemblance to its full form, the continuity of prayer and commentary is sundered for those who use the substitution:

Deliver us, Lord, we pray, from every evil, graciously grant peace in our days, that, by the help of your mercy, we may be always free from sin and safe from all distress, as we await the blessed hope and the coming of our Saviour, Jesus Christ. (Response: For the kingdom, the power, and the glory are yours, now and for ever.)

There is much one could say about the transmogrification of this prayer and the obviously Protestant origins of the congregational response, “For the kingdom, the power, and the glory” etc.7 To my mind, what is most sad about the ersatz version of the embolism is the loss of its passionate realism (and thus humility) when expressly naming the past, the present, and the future, and calling upon the intercession of great saints by name. Of course one sees a similar process of depersonalization in the removal of all the saints’ names except Our Lady’s in the Confiteor and in the neo-Eucharistic Prayers.8 I suppose when one is ecumenically swapping ideas and practices with the Protestants, one should simultaneously be careful to omit things as Catholic as those medievalisms!

But the exact details of why the Consilium plied the embolism with scissors and revved up the “active participation” component do not concern me greatly at the moment. What bothers me more is an aspect seldom commented on: such omissions and alterations in the prayer effectively elbow out, in the manner of a moody teenager, centuries of commentary before the late 20th century, making it seem quaint at best, irrelevant at worst. In this way, a continuous practice of prayer and a bountiful treasury of theology are just thrown out the window.

This is not how Catholics behave.

So, taking up again the bright strong weapons of age-old prayer, we can pray the Libera nos having in mind a meaning proper to our day:

Deliver us, O Lord, from the past evils of liturgical revolution and the loss of tradition; deliver us from present evils directed against our patrimony and the good of our families; deliver us from future evils of mendacity, hypocrisy, gaslighting, betrayal, and starvation. And by the intercession of the mighty Queen of heaven, and of the glorious apostles of Rome, Peter and Paul, and of Andrew, patron of the East, grant in Thy mercy the protection, propagation, and restoration of the Roman Rite throughout the entire Latin Church, that we may dwell in peace, free from sin, and safe from disquiet.

For the specific texts, see Kwasniewski, Illusions of Reform, 67–68.

Fiedrowicz, The Traditional Mass, 108–9.

Fiedrowicz, 108n97.

Gihr, The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, Dogmatically, Liturgically and Ascetically Explained [1902 ed.], 701–2.

Guéranger, The Traditional Latin Mass Explained, 98–99.

Koenemann, The Grace of “Nothingness,” 70.

The facts are briefly presented here: “The concluding doxology (For thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory for ever) is representative of the practice of concluding prayers with a short, hymn-like verse that exalts the glory of God. Older English translations of the Bible, based on late Byzantine Greek manuscripts, included it, but it is absent in the oldest manuscripts and is not considered to be part of the original text of Matthew 6:9–13. The translators of the 1611 King James Bible assumed that a Greek manuscript they possessed was ancient and therefore adopted the text into the Lord’s Prayer of Matthew’s Gospel. The use of the doxology in English dates from at least 1549 with the First Prayer Book of Edward VI which was influenced by William Tyndale’s New Testament translation in 1526. In the Byzantine Rite, whenever a priest is officiating, after the Lord’s Prayer he intones this augmented form of the doxology, ‘For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory: of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages’ and in either instance, reciter(s) of the prayer reply ‘Amen’. The Catholic Latin liturgical rites have never attached the doxology to the end of the Lord’s Prayer.”

St. Joseph was added at a certain point—nothing wrong with mentioning him, but for centuries other saints were always named in the liturgy who have been unceremoniously shown the door.

The most saddening part of reading this article is trying to read the old form of the Libera Nos prayer while unwillingly having the one you memorized at the Novus Ordo running loudly through your head. The unnecessary, mechanical wordiness of the New Rite is enough to make one cry. Oh, for the heavenly silence of the TLM!

You have said many times that the Traditional Latin Mass is like a great cathedral, a great edifice, most recently in the latest Kennedy Hall interview (which was so inspiring.) In this piece you demonstrate that each detail of the edifice conceals treasures which will be opened to those who knock and seek. I aim to pray along with the “embolism” more attentively now.

Often I nearly despair watching our collapsing civilization. And of my sinful complicity. How can we fight the good fight of faith? Foes rage without and within. We are so far gone. But what you and the commentators say, gives me grounds for renewed hope. I see now we cannot liberate ourselves in an activist sense. There are invisible forces at play. But the prayer we need already is available from tradition. “Libera nos!” Each word in the embolism, as explored by the commentators, is powerful, not least that we stand in need of powerful intercessors.

So we fight on. We pray on. We fight for the Mass when we pray the Mass. We fight for the Civilization created by the Mass when we pray the Mass.

Do please take a look at Robert Royal and Fr Murray on the Synod, at the Catholic Thing video where they say that Acts 15 is being invoked (is it the IL or a working group?) as a way of setting aside things from the Church’s past which supposedly impede God’s universal salvific will. (Sexual morality?)

Some of these moves are right out of the Protestant playbook with which I am sadly familiar.

Anyway what you write here is an antidote to false, activist liberation from the Christian past which is a repudiation of our need for grace. The embolism gets liberation, and whence it comes, straight.

Libera nos!