Does a Priest Need Permission to Offer the Traditional Latin Mass?

A game-changing realization: Paul VI neither legally mandated the new Mass nor altered the imprescriptable rights of the old missal

How often in recent years have we seen bishops write in diocesan decrees: “I grant permission to Frs. ABC to use the 1962 missal; no other priest is permitted to use it without requesting and receiving my permission”? How often have we heard priests say in homilies, bidding farewell to a beloved Latin Mass in this or that parish: “The bishop has not granted me a continuation of the faculties for offering this form of the Mass”? Language like this is used all the time nowadays. You can even find bishops who believe they must “grant permission” for a priest to offer the old rite in private, by himself—and priests who, for one reason or another, believe that they must have such permission.

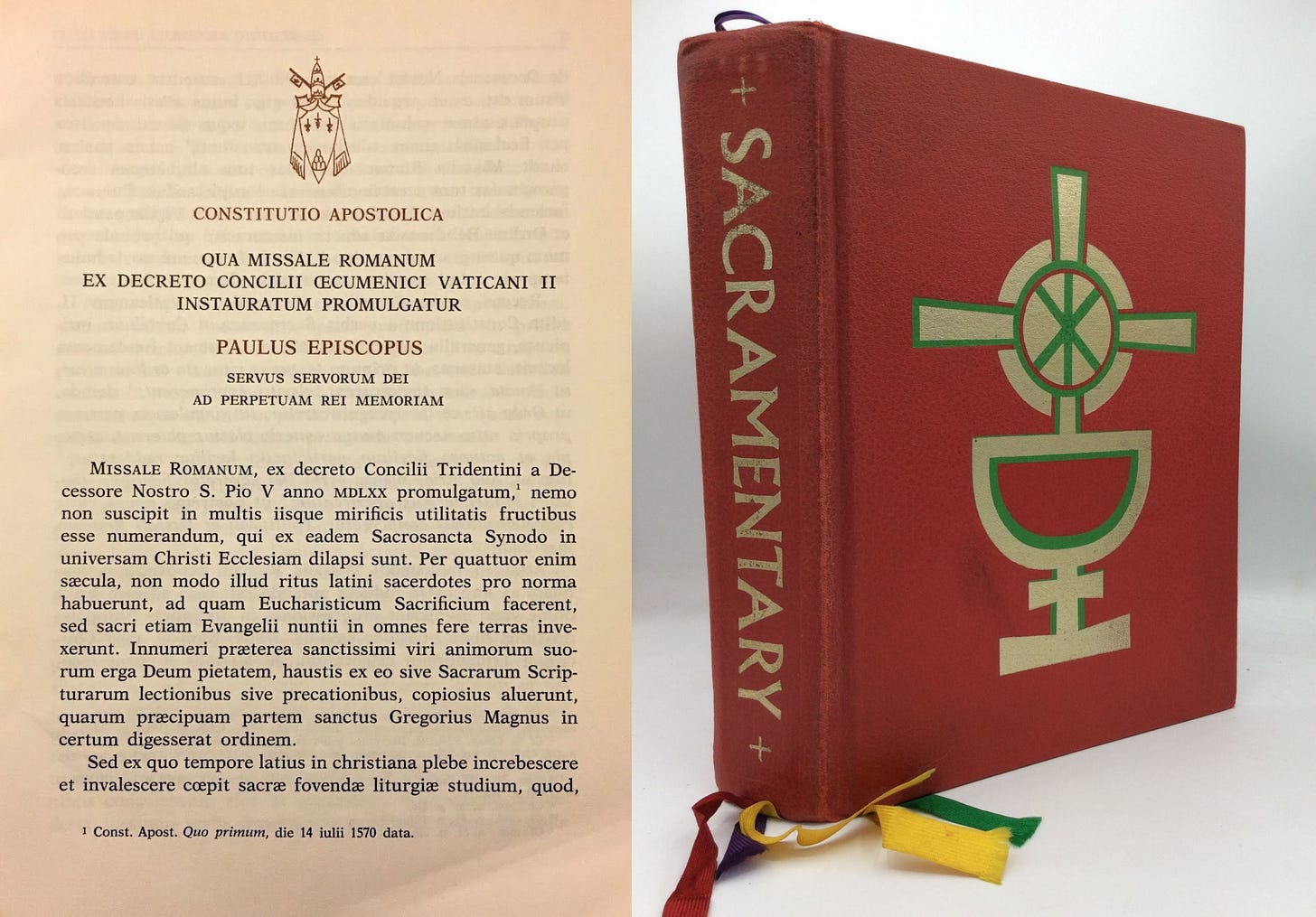

But this language of permission and faculties is faulty; indeed, it is language without a basis in fact or in law. To see this, we must begin at the beginning, with Pope Paul VI’s apostolic constitution Missale Romanum, announcing the publication of a new missal, dated exactly 56 years ago today: April 3, 1969.

For a long time, it was said by many, and assumed by nearly everyone, that with this instrument Paul VI had promulgated the new missal—and had done so in a way that abrogated the old missal and mandated the use of the new one.

This, however, is not true.

In chapter 16 of their book True or False Pope?, John Salza and Robert Siscoe demonstrate with considerable detail (pp. 493–524) that Paul VI’s document, in its Latin original, merely published and permitted the new missal and expressed a desire that it be utilized but did not either abolish the old or create a requirement to use the new. The instruction that it be universally adopted (and thus, implicitly, that it replace the rite of Pius V) was rhetorically strong but canonically meaningless. Confusion was amplified, however, by (deliberate?) mistranslations of the document that utilized language of promulgation and obligation that was not actually present in the Latin original.

In sum: Paul VI had not done what would have been required for a true mandating of the NOM and abrogation of the rite of Pius V, even though afterwards he and everyone else behaved as if he had done so. Moreover, no subsequent legislation effectively imposed the necessary use of the missal of Paul VI, leaving priests of the Latin rite legally free to use the old missal; indeed, Pius V’s Quo Primum still remains in force in that regard (and as I have argued in my tract True Obedience in the Church, that bull is far more than a “mere disciplinary decree”). That is the basis of Benedict XVI’s judgment that the old missal was never abrogated (or even obrogated, in the sense of one law replaced by another).

Obviously relevant is the making of critical distinctions between what may be intended, what is actually legislated, and what is legislatable (or not). A modern canonist who develops this theme is Réginald-Marie Rivoire, FSVF, in his tract Does “Traditionis Custodes” Pass the Juridical Rationality Test? As Fr. Rivoire shows, not even Traditionis Custodes changes the findings that Salza and Siscoe summarize; indeed, it is pretty clear that its ghostwriters didn’t even grasp the issues discovered by more careful canonists. And this, too, is in God’s Providence.

A priest once wrote to me that all this seems “too good to be true,” because it undermines the basis of Traditionis Custodes and, well, most of the attitudes and policies of the past five and a half decades concerning the obligatory use of the new missal. I thought that I should approach a friend, a highly prominent canon lawyer (I will not say more; qui legit, intelligat), and ask him for his assessment of the Salza-Siscoe case.

He graciously responded:

In answer to your question, I, too, find the position of John Salza and Robert Siscoe coherent and compelling. Pages 499 to 502 of Chapter 16 contain the heart of what I would give as a canonical response. Pope Paul VI never abrogated the Roman Missal of Pope Pius V because he could not juridically abrogate it. This explains the position of the nine Cardinals commissioned by Pope John Paul II to answer two questions regarding the Roman Missal of Pope Paul VI.

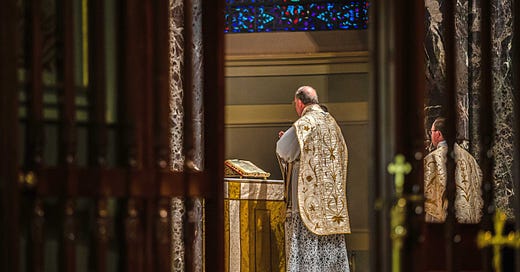

In fact, the Usus Antiquior continued to be celebrated after the publication of the Usus Recentior. I know, from a conversation with a venerable Benedictine Abbot, that when the Abbot of his monastery approached the competent Roman Congregation after the publication of the Roman Missal of Pope Paul VI, indicating that the radically reduced form of the Roman Rite was spiritually too impoverished for the offering of the Holy Mass by monks, the abbot was told to continue to have the monks celebrate according to the Usus Antiquior. At the same time, the right of an individual priest to celebrate according to the Usus Antiquior as a valid and indeed most beautiful form of the Roman Rite has never been taken away because it cannot juridically be taken away.

What happened in what pertains to the Roman Missal after the Council of Trent is radically different from what happened after the Second Vatican Council: Pope Pius V corrected abuses in a form of the Roman Rite which remained substantially the same as it had been from the time of Pope Gregory the Great and earlier; Pope Paul VI presented a new form of the Roman Rite, not claiming abuses in the Usus Antiquior. I do not question the validity of the new form of the Roman Rite, but I maintain that it cannot be said to replace the more ancient form of the Roman Rite.

As this response points us to the core of the case made by Salza and Siscoe, I thought it would be helpful to include in this post what they write on pages 499 to 502. The section is entitled “Did Paul VI Abrogate Quo Primum?”1

In its Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium (December 4, 1963), the Second Vatican Council decreed a “reform” of the Roman Missal. What followed the council’s decree in the years to come was a staggering number of pronouncements, which gradually introduced changes into Catholic worship that brought it more in line with the reforms of the Protestant innovators. The earliest changes targeted the Traditional Mass, until Paul VI released his Apostolic Constitution, Missale Romanum, on April 3, 1969, in which he announced the publication of the New Mass. Following the issuance of Missale Romanum, the Congregation for Divine Worship (not Paul VI) “promulgated” the New Mass by issuing Celebrationis Eucharistiae on March 26, 1970.2 Other pronouncements from the Congregation followed, even one that attempted to ban the old Mass by mandating the exclusive use of the New Missal.3

From the time these pronouncements were unleashed on the Church over four decades ago, Catholics were divided over their meaning and level of authority. Specifically, the Liberal and Neo-conservative Catholics argued that Paul VI legally abrogated Quo Primum and that the old Mass was forbidden. Traditional Catholics, on the other hand, maintained that the old Mass was never juridically abrogated, nor was the new Missal ever juridically promulgated as a binding law. In the midst of this confusion, the priests who continued to say the old Mass and refused to say the New were (and still are) persecuted by their Liberal-minded counterparts, their bishops and fellow priests.

The position of the Traditionalists with respect to the Old Mass was officially (although not publicly) vindicated during the reign of John Paul II, who appointed a commission of nine Cardinals4 to study the issue and provide the answers to two questions:

1) Did Paul VI or any lawful authority legally suppress the Traditional Mass?

2) Was any priest free to say the Old Mass without special permission?

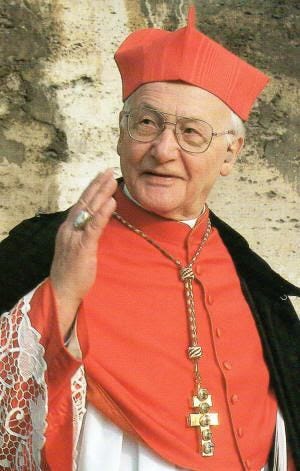

In a 1995 interview, Cardinal Stickler, who was one of the nine Cardinals, explained the findings of the Commission as well as some other interesting, behind-the-scenes information about the subject.

Ats point, Salza and Siscoe quote from an interview with Cardinal Stickler (with emphases added):

Question: Did Pope Paul VI actually forbid the Old Mass?

Cardinal Stickler: Pope John Paul asked a commission of nine cardinals in 1986 two questions. Firstly, did Pope Paul VI or any other competent authority legally forbid the widespread celebration of the Tridentine Mass in the present day? No. He asked Benelli explicitly, “Did Paul VI forbid the Old Mass?” He never answered—never yes, never no. Why? He couldn’t say, “Yes, he forbade it.” He couldn’t forbid a Mass which was from the beginning valid and was the Mass of thousands of saints and faithful. The difficulty for him was he couldn’t forbid it, but at the same time he wanted the new Mass to be said, to be accepted. And so he could only say, “I want that the new Mass should be said.” This was the answer all the princes gave to the question asked. They said: the Holy Father wished that all follow the new Mass.

The answer given by eight (of the) cardinals in ’86 was that, no, the Mass of St. Pius V has never been suppressed. I can say this: I was one of the cardinals. Only one was against. All the others were for the free permission: that everyone could choose the old Mass. That answer the Pope accepted, I think; but again, when some bishop’s conferences became aware of the danger of this permission; they came to the Pope and said: “This absolutely should not be allowed because it will be the occasion, even the cause, of controversy among the faithful.” And informed of this argument, I think, the Pope abstained from signing this permission. Yet, as for the commission—I can report from my own experience—the answer of the great majority was positive.

There was another question, very interesting: “Can any bishop forbid any priest in good standing from celebrating a Tridentine Mass again? The nine cardinals unanimously agreed that no bishop may forbid a Catholic priest from saying the Tridentine Mass. We have no official prohibition and I think the Pope would never establish an official prohibition.5

If you want to read more about this commission of cardinals, you can find the minutes taken by Cardinal Dario Castrillón-Hoyos translated at New Liturgical Movement.

Now back to Salza and Siscoe:

In spite of the finding of the nine Cardinals, most bishops during the reign of John Paul II continued to forbid the Old Mass (either out of malice or ignorance) and persecute the priests who continued to celebrate it. Traditional priests were even labeled schismatic for celebrating the Tridentine Mass, and forced to endure an unimaginable crisis of conscience.

But in 2007, to the shock and dismay of the Left (and, no doubt, many on the Sedevacantist Right), Pope Benedict XVI issued the Motu Proprio, Summorum Pontificum, which publicly declared what had been concluded by the commission of nine Cardinals twenty years earlier. Contrary to what virtually all Catholics throughout the years had been led to believe, Pope Benedict confirmed that the Old Mass had never been juridically abrogated and, indeed, was always permitted—just as the Traditional Catholics had always maintained.

In a statement that sent shockwaves throughout the Church, Pope Benedict declared [in Summorum Pontificum]: “I would like to draw attention to the fact that this Missal [the Traditional Mass] was never juridically abrogated and, consequently, in principle, was always permitted.” In remedying this grave injustice, the Pope stated the obvious: “What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful.”

For almost forty years, the entire Catholic world had been led to believe that the Old Mass was abrogated by Pope Paul VI, but this impression was entirely false. The old Mass was never juridically abrogated, just as the New Mass was never juridically promulgated as a universally binding law. This injustice certainly underscores what God wills to permit His Church to suffer, and with regard to the source and summit of Catholic worship, no less. Indeed, God can and does permit such evils to afflict His Mystical Body, but never at the cost of compromising the Church’s charism of infallibility. While this confusion concerning the Old vs. New Mass was (and still continues to be) a source of consternation among the faithful, it can hardly compare [it terms of problems of legality] with other crises God has willed to permit, such as what we learned in Chapter 8, when God permitted synods, called and overseen by Popes, to issue erroneous decrees (e.g., mistakenly declaring that the ordinations performed by previous Popes were null and void), and then be contradicted by other synods, also called and overseen by Popes, which decreed the exact contrary.

At the end of the chapter, Salza and Siscoe commence their refutation of Fr. Cekada’s position as to Paul VI’s apostolic constitution Missale Romanum—a debate that does not concern me at present, since the case already made is water-tight. (Those who would like to read the whole of chapter 16, including its refutation of the sedevacantists on this particular point, will find it in PDF form here.)

Now, a chain is only as strong as any one of its links; and a chain that is hanging from a hook is only as strong as the hook itself. The hook for all legislation concerning the Novus Ordo is Paul VI’s apostolic constitution Missale Romanum. If you follow the footnotes (like a trail of breadcrumbs), you’ll see that all subsequent legislation on the new missal refers back to this document. Hence, if Paul VI therein legally promulgated and mandated the exclusive use of the new missal, then yes, a priest today would need some kind of permission to step outside of that mandate and offer Mass with a different missal; but if, as Salza and Siscoe have shown, it did not legally promulgate and mandate the exclusive use of the new missal (thereby abrogating the old missal and obrogating Quo Primum), then the use of the new missal was (and is) not mandatory and the use of the old missal was (and is) not prohibited or prohibitable; indeed, its use is always permitted to a priest of the Latin rite.

This is not a coin toss. Summorum Pontificum in fact came down clearly in favor of the latter position, in accordance with the findings of the commission of cardinals: the old rite’s legal status is summed up in three phrases: “never juridically abrogated… always permitted… cannot be forbidden.” Traditionis Custodes, although it rescinded some of the provisions of Summorum Pontificum, did nothing to alter the facts surrounding the text and the legal force of Paul VI’s constitution.

So, if a bishop is saying to a priest: “You need my permission to say the old Mass,” or “You’re not permitted to use the preconciliar missal,” or “You are required to use the new missal,” or any variation on that theme, he is either the victim or the perpetrator of a falsehood; he is undermining the rule of law; he is guilty of overreach and spiritual abuse. To the extent that he is genuinely ignorant of the facts and therefore mistaken in good faith about what is and is not required (and in my experience, most bishops are terribly ignorant of the entire history of liturgy and of the missals), it will go better for him on the day of judgment. That being said, priests to whom God has given the grace of a love of tradition and souls who now rely on them for spiritual nourishment are not thereby released from their obligation, coram Deo et secundum consuetudinem ecclesiae, to continue to offer the traditional Roman Rite.

It is my opinion that priests have been habituated for so long to think in terms of faculties needed to hear confessions, to preach, or to preside at marriages that they unconsciously begin to think they need faculties to do just about anything sacramental or liturgical. They think they need a faculty to offer Mass, to pray this or that version of the Divine Office, to bless holy water with the Rituale Romanum, or whatever the case might be. This is a false extrapolation of faculties into areas where the concept is meaningless. A priest ordained in and for the Latin-rite Church is empowered to offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in any valid and licit form of his rite; indeed, he has a positive right to do so, which can be restrained only for specifically delimited proven faults against the priesthood.

It is time we stop carelessly throwing around the terms “permission” and “faculties.” Let us use them precisely and correctly.

In short:

Priests do not need permission to offer the traditional Mass.

Priests have never needed permission to offer the traditional Mass.

They cannot be forbidden from doing so.

They cannot be required to use only the new missal.

It is not spiritually healthy for bishops to be allowed to abuse their pastoral power and for priests to allow themselves to be so abused. I sincerely hope that the information presented above will help all clergy, regardless of their level, to think, choose, and act in accordance with the truth.

Related reading:

“Do Priests or Religious Need Special Permission to Pray a Pre-55 Breviary?”

“Ending Seventy Years of Liturgical Exile: The Return of the Pre-55 Holy Week”

In the interests of space, I have not included all the footnotes.

[Note in original] As we will further discuss later in the chapter, because the New Mass was “promulgated” by the Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship (and not the Pope), it not only fails to trigger the infallibility of the Church, but some also argue it is necessarily rendered null by Quo Primum, which was promulgated by the Pope (St. Pius V). An inferior cannot annul a superior’s law. They further argue that the New Mass is technically illicit (illegal but not invalid) by virtue of being contrary to the legislation of Quo Primum.

[Note in original] See the Notice Conferentia Episcopalium (October 28, 1974). It must be noted that this Notice, as with other pronouncements regarding the New Mass during the 1970s, was not signed by the Pope and did not appear in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis where new laws must be published to take legal effect (because Paul VI never mandated the exclusive use of the New Mass in the 1969-1970 decrees, the 1974 Notice would have been considered a new law requiring publication in the Acta).

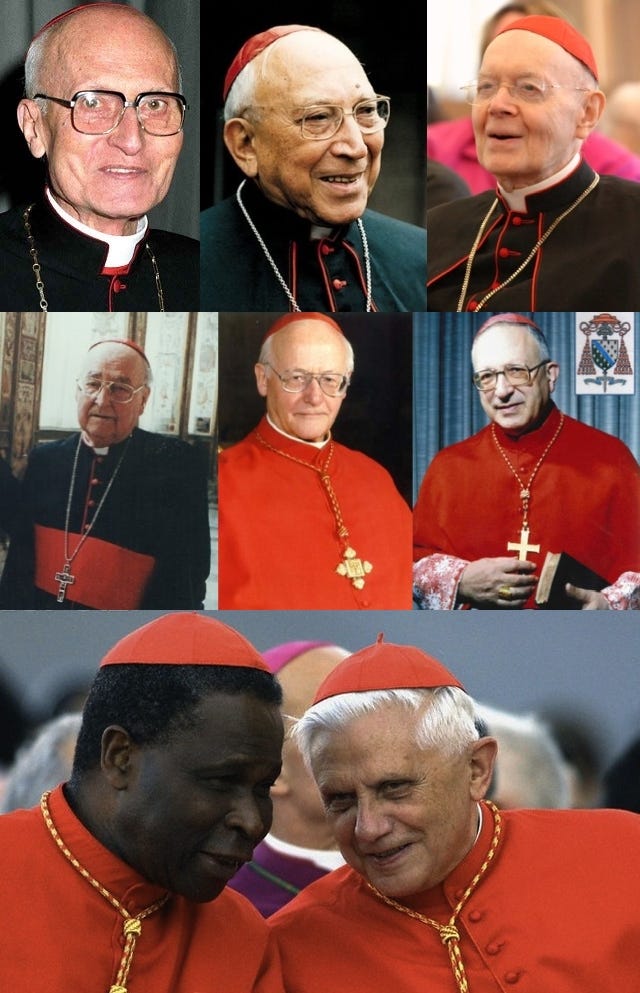

Cardinals Ratzinger, Mayer, Oddi, Stickler, Casaroli, Cantin, Innocenti, Palazzini, and Tomko.

The Latin Mass, Summer 1995, page 14.

This is all very good for the missal and the mass, and I'd be even more delighted to hear similar arguments for the other sacraments.

I know of a diocesan church where the TLM is permitted (praise God), but the faithful are not allowed to be shriven in the old rite, or wed in the old rite, or have their infants baptized in the old rite. It would be nice to get some arguments in favor of those sacraments, too.

Thank you once again for these increasingly-clear clarifications of the Truth. With each passing day I see more plainly how our earthly lives driven by this bewildering dichotomy of the Truth striving for its rightful freedom against the crushing legalism of the world, flesh and devil (a cause too readily taken up by the ones responsible for the freedom of Truth..).

And this realization is always followed up in my mind with the "clincher" colloquial summation of the whole N.O. paradigm: "But he hasn't anything on!", said the little boy about the emperor's new clothes. It's all a massive deception by the anti-Christ forces of the world, putting the Church in the position of the obsequious emperor.