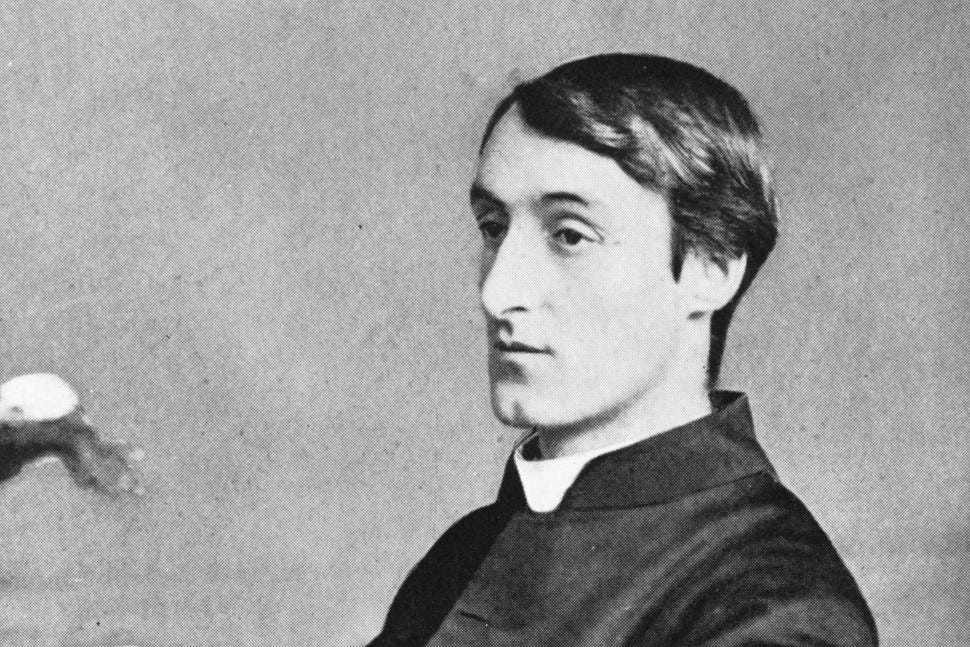

Exploring a Poem: Hopkins’ “The Sea and the Skylark”

Unravelling the delicious tangle of one of the priest-poets' verses

As I said in my last poetry post, Hopkins is in some way the Catholic poet. Unlike other greats of the Catholic literary revival, Hopkins was an anguished wordsmith with a strange but wonderful genius for rhyme, meter, the play of words and imagery.

Born in 1844, he was baptized in the Anglican church. Initially drawn to visual art, he was one of nine creative and intense siblings: one joined an Anglican sisterhood; another composed music; his brother Lionel became a renowned expert on the Chinese language; two other brothers were successful artists.

Enrolled at Oxford in 1863, Hopkins studied classics and began taking religion seriously. This lead to his reception into the Catholic Church on October 21, 1866, by John Henry Newman—a decision that separated him from his family and some friends. The call to asceticism clashed with his love for beauty, however, and while teaching at the Birmingham Oratory following his graduation from Oxford, he burnt a number of his poems shortly before joining the Jesuit novitiate.

Believing that the writing of poetry was not the task of a Jesuit, Hopkins’ poetic pen was silent for seven years, although his insatiable creative impulse found outlet in a detailed journal, in sketching, and in composing music.

In 1872, Hopkins’ reading of Duns Scotus encouraged him to think that a harmony between the writing of poetry and living a serious religious life was possible. The 1875 wreck of the passenger steamship The Deutschland inspired one of his Jesuit superiors to commission a poem on the incident, and Hopkins the poet came back to life. With ideas that had fermented in seven years of silence, Hopkins’ genius burst forth in The Wreck of the Deutschland.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.