Five Poems Every Catholic Should Memorize

Catholic verse at its best—and most diverse

In his short book on the spiritual life We Live with Our Eyes Open, the English Benedictine Hubert van Zeller comments that “What most of us need to cultivate is the innocent eye which is not ashamed to open in wonder.” We open ourselves up to sloth and listlessness when we loose our ability to get lost in wonder. “The too enquiring mind is obviously more of a liability than an asset; but the mind which is too listless to enquire might just as well not exist at all.”

Wonder, which goes hand in hand with curiosity, is a key to keeping our eyes open to the beauties of both the natural life and the supernatural life: “Hardly surprising that Christ so often gave us children as our models: to the child there is nothing commonplace, nothing which cannot be vested with some sort of interest. Even if we can’t welcome the normal with a glad cry of surprise, there is no reason why we should deny it the beauty which belongs to it. Beauty jumps out of the dustbin if you let it.”

I believe that the cultivation of wonder, of a desire to be more and more open to the marvel of what is, is one of the primary reasons we ought to read and memorize poetry. If Dom Hubert is right, we need a mental and spiritual ointment to rub on our stiffened imaginations and limber them up again so that our hearts do indeed “leap up” when we “behold a rainbow in the sky.” Whatever his other issues, at least Wordsworth’s childlike wonder perdured into his older years: “So was it when my life began; / So is it now I am a man; / So be it when I shall grow old, / Or let me die!”

The poet’s task could be put this way, then: to capture beauty whenever he sees it jump out of the dustbin, or sock drawer, or rotten forest log, or crimson-lined sunset cloud, and remind others to look there themselves.

The marvelous thing about poetry is that it allows us to get in on another’s moment of wonder; and then we have a little piece of his wonder to view the world through. Imagine each great poem you learn as if it is a sliver of stained glass: once your pocket is full of them, you have many lenses you can view the world through. Sometimes the colored glass accents or reveals certain features of the view you couldn’t or didn’t see before. Sometimes they make visible objects you couldn’t see without them. Other times they hide things from view so that you can see how much better or worse off the scene might be with only one item. When you share these shards of glass with others, you begin to have a common language of vision and interpretation: even though you may notice differences, viewing the same scenes through beautiful shards of glass gives a commonality to different viewers’ experiences.

I believe this phenomena of shared experience, shared underlining and highlighting of wonder, is one of the important reasons everyone should learn, love, and share poetry. Through the artistry of the poet, one also begins to have better ways of describing shared experience. The words “my heart leaps up / when I behold a rainbow in the sky” is both more descriptive of the experience of seeing a rainbow and more memorable.

In this piece, I’d like to draw attention to five specifically Catholic poems which deserve to be common panes of stained glass among us. Many poems could have been chosen for an article with a title like this one, and while my list is certainly not definitive, I’ll still explain my rationale in choosing these five.

I choose to limit myself to poems composed in English. Translations of poetry can be decent but they are never as successful as the originals. We might lament the dearth of good English writers who were also Catholic. Ronald Knox and John Senior (among others) complained that English has been for so long a “Protestant” language, spoken in predominantly Protestant cultures, that it lacks the Catholic riches of some other languages: for instance, St Thomas Aquinas’s hymns in Latin, or Dante’s Comedy in Italian, or St John of the Cross’s mystical verses in Spanish, or the rhapsodies of Charles Péguy and Paul Claudel in French. I wish I could include one of the Metaphysical Poets—even perhaps a stanza of Milton—but they do not belong to the fold. As it is, two of my most famous authors are converts from Anglicanism.

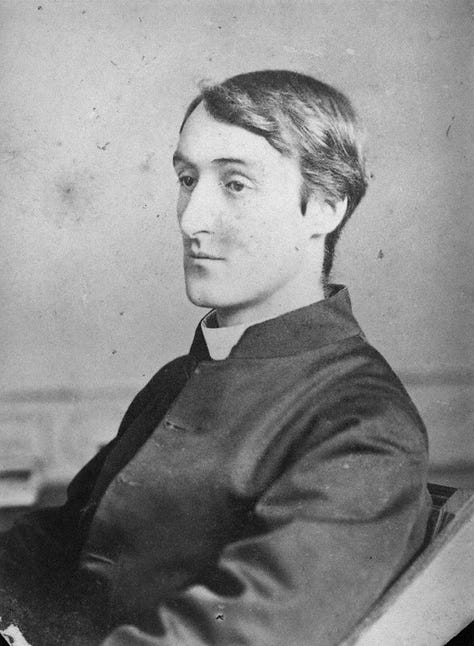

Lead, Kindly Light

This famous hymn was written by the young Newman on his trip to Italy in 1833. He wrote: “We were becalmed for whole week in the Straits of Bonifacio, and it was there that I wrote the lines, Lead, Kindly Light, which have since become so well known.”

First entitled “the Pillar of the Cloud,” the verses were published in British Magazine the following year, and set to music in 1869, to the tune Lux Benigna, specifically composed for these words by John Bacchus Dykes. The text acquired multiple other popular tunes over the years, and continues to be sung to various melodies today. It became wildly popular, and has found its way around the world, being sung by survivors of the Titanic as they escaped the sinking ship, by miners trapp ed inside a mine shaft in 1909, and by British troops in World War I. It found its way into a novel by Thomas Hardy, and its opening line is the motto for schools as far flung as the UAE and India.

Lead, Kindly Light, amidst th'encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home,

Lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene; one step enough for me.

I was not ever thus, nor prayed that Thou

Shouldst lead me on;

I loved to choose and see my path; but now

Lead Thou me on!

I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears,

Pride ruled my will. Remember not past years!

So long Thy power hath blest me, sure it still

Will lead me on.

O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till

The night is gone,

And with the morn those angel faces smile,

Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile!

If it’s good enough for school children in the UAE, sinking Titanic passengers, and coal-miners, it’s good enough for me!

Its most piercing theological theme is that of not being able to see the totality of God’s plan but learning to be content with seeing just one step at a time:

I do not ask to see

The distant scene; one step enough for me.

I fear that beautiful English like this is becoming more and more unintelligible to our contemporaries simply because it uses slightly archaic sentence construction and vocabulary. Since few people read assiduously, our glorious English language is not learned at a level above that of tweets and news stories—which, alas, is not a very high level.

If we want to continue to be able to read, speak, and especially think at a high level, we must embrace the study of the liberal arts. Too few Catholics today are properly educated, and this limits their ability to love the beautiful arts their predecessors in faith produced.

So… read, speak aloud, listen to, memorize the poetry, learn the books, music, and art of the Western tradition. Otherwise… darkness. The kindly light of God’s grace has also produced the kindly light of philosophy and the arts and all that we term “culture” in our world. To be sure, a new Dark Age is already upon us. What is in our hands, however, is how dark it will be, at least for us, and whether or not we will be among the pockets of light that will shine nevertheless.

The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air We Breathe

Hopkins is in some way the Catholic poet. Newman wrote some fine poems, but he was not a poet primarily. Chesterton was Catholic, but he is not especially known for his verse, which is quirky rather than great. Belloc wished to be remembered above all as a poet, but whether it is chance or the quality of his verse, history remembers him more as an historian and essayist. Tolkien was a Catholic, but his mythic poems were not directly about Catholic topics. Lewis wasn’t Catholic (but almost, sometimes).

Gerard Manley Hopkins, though, was a poet through and through. He agonized over his innovative writing. His genius was such that he invented new poetic forms, based on his concept of sprung rhythm. Intended to reflect the flowing quality of speech rather than the pounding footfall of iambic pentameter, Hopkins’ sprung rhythm consists of one- to four-syllable feet that start with a stressed syllable.

In his masterpiece on the Virgin Mary, we hear his verses tumbling over each other like a brook in springtime, full of new snowmelt. It was written in May 1883 for the celebration of May Day at Stonyhurst College, where Hopkins was teaching Latin and Greek. It’s really hard to know what to say of such a great work besides “read it and memorize it”!

I’ll make a few comments after the poem. For now, keep your eyes peeled for the technique of enjambment, where the end of one line runs straight into the next, without any punctuation: this necessitates careful attention to the meaning of the text, revealed through careful inflection when recited aloud.

Wild air, world-mothering air,

Nestling me everywhere,

That each eyelash or hair

Girdles; goes home betwixt

The fleeciest, frailest-flixed

Snowflake; that’s fairly mixed

With, riddles, and is rife

In every least thing’s life;

This needful, never spent,

And nursing element;

My more than meat and drink,

My meal at every wink;

This air, which, by life’s law,

My lung must draw and draw

Now but to breathe its praise,

Minds me in many ways

Of her who not only

Gave God’s infinity

Dwindled to infancy

Welcome in womb and breast,

Birth, milk, and all the rest

But mothers each new grace

That does now reach our race—

Mary Immaculate,

Merely a woman, yet

Whose presence, power is

Great as no goddess’s

Was deemèd, dreamèd; who

This one work has to do—

Let all God’s glory through,

God’s glory which would go

Through her and from her flow

Off, and no way but so.

I say that we are wound

With mercy round and round

As if with air: the same

Is Mary, more by name.

She, wild web, wondrous robe,

Mantles the guilty globe,

Since God has let dispense

Her prayers his providence:

Nay, more than almoner,

The sweet alms’ self is her

And men are meant to share

Her life as life does air.

If I have understood,

She holds high motherhood

Towards all our ghostly good

And plays in grace her part

About man’s beating heart,

Laying, like air’s fine flood,

The deathdance in his blood;

Yet no part but what will

Be Christ our Saviour still.

Of her flesh he took flesh:

He does take fresh and fresh,

Though much the mystery how,

Not flesh but spirit now

And makes, O marvellous!

New Nazareths in us,

Where she shall yet conceive

Him, morning, noon, and eve;

New Bethlems, and he born

There, evening, noon, and morn—

Bethlem or Nazareth,

Men here may draw like breath

More Christ and baffle death;

Who, born so, comes to be

New self and nobler me

In each one and each one

More makes, when all is done,

Both God’s and Mary’s Son.

Again, look overhead

How air is azurèd;

O how! nay do but stand

Where you can lift your hand

Skywards: rich, rich it laps

Round the four fingergaps.

Yet such a sapphire-shot,

Charged, steepèd sky will not

Stain light. Yea, mark you this:

It does no prejudice.

The glass-blue days are those

When every colour glows,

Each shape and shadow shows.

Blue be it: this blue heaven

The seven or seven times seven

Hued sunbeam will transmit

Perfect, not alter it.

Or if there does some soft,

On things aloof, aloft,

Bloom breathe, that one breath more

Earth is the fairer for.

Whereas did air not make

This bath of blue and slake

His fire, the sun would shake,

A blear and blinding ball

With blackness bound, and all

The thick stars round him roll

Flashing like flecks of coal,

Quartz-fret, or sparks of salt,

In grimy vasty vault.

So God was god of old:

A mother came to mould

Those limbs like ours which are

What must make our daystar

Much dearer to mankind;

Whose glory bare would blind

Or less would win man’s mind.

Through her we may see him

Made sweeter, not made dim,

And her hand leaves his light

Sifted to suit our sight.

Be thou then, O thou dear

Mother, my atmosphere;

My happier world, wherein

To wend and meet no sin;

Above me, round me lie

Fronting my froward eye

With sweet and scarless sky;

Stir in my ears, speak there

Of God’s love, O live air,

Of patience, penance, prayer:

World-mothering air, air wild,

Wound with thee, in thee isled,

Fold home, fast fold thy child.

Mary's color of blue appears throughout in the sustained metaphor of the Mother of God as the sky which mantles the world. This is a remarkable portrayal of the almost-dogma of Mary as Mediatrix of All Graces. Does the air interfere with the sunlight? No. “Through her we may see him / Made sweeter, not made dim, / And her hand leaves his light / Sifted to suit our sight.” Would the sunlight be much good without the atmosphere? Again, no. If “…air not make / This bath of blue and slake / His fire, the sun would shake, / A blear and blinding ball / With blackness bound…”

Rather than distracting us from God, as the Protestants fear, Mary—this blue heaven—transmits and perfects “seven or seven times seven” the sunbeams of Christ’s grace. Mary is not only mediatrix of grace, but in some way the gift itself: “more than almoner, / The sweet alms’ self is her” since she draws mankind to God. The longest of the poems in my list of five, I believe this one is perhaps the most worthwhile to memorize. Join me in the endeavor!

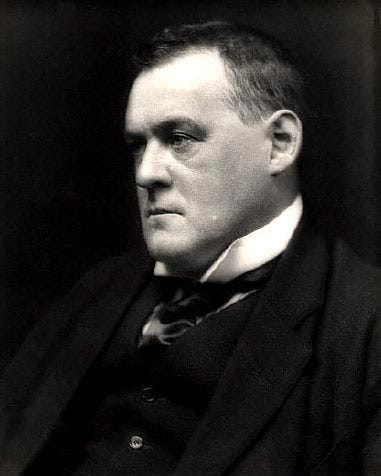

The Pelagian Drinking Song

Time for a comedic interlude. Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953) was a great friend of G.K. Chesterton, and as far as my study of both of them has shown me, he was the more scholarly of the two. It’s a big claim, I know, but whereas Chesterton was a journalist who dashed off verse as he was able, and wrote the occasional history book based on a general knowledge of the topic, Belloc carefully researched his many detailed historical studies—which included his 1912 monumental History of England in eleven volumes, co-authored with John Lingard (of which I’ve read his shorter, that is, 670-page, single-volume condensation). Chesterton would never have had the patience to research and write such a work. I’m not sure about his poetry-writing process, but while it certainly contains some gems (such as The Ballad of the White Horse), many verses appear to be dashed off like Chesterton’s journalism. Even The Ballad of the White Horse has come under heavy fire from no-less a man of letters than Tolkien.

My favorite Belloc poem is among the drinking songs he wrote. This one manages to be a lesson in theology at the same time. Its theme is Pelagius, whose doctrine denies original sin resulting from the fall and claims instead that humans can achieve perfection without a new grace. The “grace” of free will was sufficient: consequently infants did not need to be baptized since they did not bear original sin. Pelagius thought that if sin were inevitable in man because of the fall, it could not be sin, for God could not ask something of man—namely, sinlessness—that was humanly impossible.

Belloc has no truck with that. Instead, he humorously upholds infallible dogma and flowing beer as the blessings of Christendom.

Pelagius lived at Kardanoel

And taught a doctrine there

How, whether you went to heaven or to hell

It was your own affair.

It had nothing to do with the Church, my boy,

But was your own affair.

No, he didn’t believe

In Adam and Eve

He put no faith therein!

His doubts began

With the Fall of Man

And he laughed at Original Sin.

With my row-ti-tow

Ti-oodly-ow

He laughed at original sin.

Then came the bishop of old Auxerre

Germanus was his name

He tore great handfuls out of his hair

And he called Pelagius shame.

And with his stout Episcopal staff

So thoroughly whacked and banged

The heretics all, both short and tall—

They rather had been hanged.Oh he whacked them hard, and he banged them long

Upon each and all occasions

Till they bellowed in chorus, loud and strong

Their orthodox persuasions.

With my row-ti-tow

Ti-oodly-ow

Their orthodox persuasions.Now the faith is old and the Devil bold

Exceedingly bold indeed.

And the masses of doubt that are floating about

Would smo ther a mortal creed.

But we that sit in a sturdy youth

And still can drink strong ale

Let us put it away to infallible truth

That always shall prevail.

And thank the Lord

For the temporal sword

And howling heretics too.

And all good things

Our Christendom brings

But especially barley brew!

With my row-ti-tow

Ti-oodly-ow

Especially barley brew!

A rather poor recording can be found below—although it is a bit different from the version I know and would love to record someday (you can hear me sing a verse in the voiceover).

As Kingfishers Catch Fire

The fourth poem in this collection is another Hopkins masterwork.

This poem displays Hopkins’ sympathy to Dun Scotus’ philosophy of haecceitas (Latin for “thisness”). In contradistinction to Aquinas and other scholastics, Scotus emphasized the irreducible individuality of things as their essence, instead of viewing their essence as more properly derived from the genus or type of thing they were. For example, Scotus would have said that the essence of a man named Bill was best or primarily captured in the fact that he was this man, with his own particular history, hair color, likes and dislikes, insight and ignorance. Aquinas would have said that the essence of Bill was that he was a particular type of thing: a member of the human species, a male of that species, of a particular country, etc., and so would have seen his essence not so much in his individuality as in his belonging to a particular species or genus of thing, all the members of which shared certain defining characteristics. (A fuller account would have need an article all to itself.)

The important thing in all of this for our poet, though, is that the magic of God’s creation is revealed in individuals as individuals: each individual person or animal “speaks and spells” wonder by being itself first, not primarily by being a member of a species: we marvel and delight in the individual more than in the abstraction we are able to make of its belonging to a type.

Existence “finds tongue to fling out broad its name,” and as for kingfishers and dragonflies, so for man—but better, since he is made in the image of God. For the “just man” to “justice” (a verb) is in fact for Christ to “Christ” (as a verb)—that is, be Christ in the Father’s eyes. The man in a state of sanctifying grace “acts in God's eye what in God’s eye he is—Chríst.”

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies dráw fláme; As tumbled over rim in roundy wells Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell's Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name; Each mortal thing does one thing and the same: Deals out that being indoors each one dwells; Selves—goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I do is me: for that I came.

Í say móre: the just man justices;

Kéeps gráce: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God's eye what in God’s eye he is—

Chríst—for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

Chatting with my friend Augustine, a sophomore at Wyoming Catholic College (and for whom this poem was his introduction to poetry), we see how Hopkins in the second stanza shows man in relation to himself and then in relation to God, and finally in relation to community. Justice can be seen as man in right relation to himself; justice is also operative in man’s right relation to God; and finally, man “in ten thousand places” is man seen in relation to his fellow men—as imaging Christ both to them and to the Father.

Somehow Hopkins uses very particular images to express very general concepts: the stones that ring could be understood as “ringing” in the sense of sounding when knocked together, but also as making concentric rings in the well water they splash into. It’s clear this poem is meant for reading out loud: you can hear the ringing of stones and bells in the “ings” of the consecutive “string, hung, swung, tongue, and fling.”

The “bow” of the bell is the base of the bell where the tongue of the bell hits it. The “roundy well” sounds like the echo of a well: in all of this, we see Hopkins tying together the sound and signification of words to wring out the greatest possible meaning—“ring” both indicates and sounds like the reality he is trying to convey; truly a wringing of the word!

As a side note, kingfishers are a rare sight in Wyoming, although they do live there. Small, incredibly fast, shy, they live near less frequented water sources. I once saw one flash over the river that runs through Lander. What struck me more than the color (I wasn’t close enough to see much besides the fact that it was a kingfisher) was the incredible speed with which it flew down the avenue of trees that lined the river. Try and see a kingfisher someday if you’ve never had that chance before.

Resurrected but Still Joseph’s Son

This is the most “modern” poem of our five. Attributed to a “Sr. Mary Ada OSJ,” it has been widely shared on the internet. I’ve searched extensively, and have been unable to dig up any biographical information about the author. I suspect she was a religious sister of the 40s or 50s whose one poem became popular, and little or no record of her survives. That is rather fitting, I suppose, for one who is writing about Joseph, the hidden saint. I include it in the top five with a little bit of trepidation, given its relative obscurity, but you can judge for yourself whether or not it is a masterful and imaginative work that accomplishes what I spoke about at the beginning: the stirring of wonder at familiar sights or even concepts and biblical events (as in this case).

In the splendor of the resurrection, Christ did not lose his humanity. The uncreated Word of God’s created humanity now immortal, he still loved his father and mother. It needs little commentary, but do read it out loud to someone: that is how I first heard it, and poetry was meant to be heard more than read.

Limbo

The ancient greyness shifted

Suddenly and thinned

Like mist upon the moors

Before a wind.An old, old prophet lifted

A shining face and said:

“He will be coming soon.

The Son of God is dead;

He died this afternoon.”A murmurous excitement stirred all souls.

They wondered if they dreamed—

Save one old man who seemed

Not even to have heard.And Moses standing,

Hushed them all to ask

If any had a welcome song prepared.

If not, would David take the task?And if they cared

Could not the three young children sing

The Benedicite, the canticle of praise

They made when God kept them from perishing

In the fiery blaze?A breath of spring surprised them,

Stilling Moses’ words.

No one could speak, remembering

The first fresh flowers,

The little singing birds.Still others thought of fields new ploughed

Or apple trees

All blossom–boughed.

Or some, the way a dried bed fills

With water

Laughing down green hills.The fisherfolk dreamed of the foam

On bright blue seas.

The one old man who had not stirred

Remembered home.And there He was

Splendid as the morning sun and fair

As only God is fair.

And they, confused with joy,

Knelt to adore

Seeing that He wore

Five crimson stars

He never had before.No canticle at all was sung.

None toned a psalm, or raised a greeting song.

A silent man alone

Of all that throng

Found tongue —

Not any other.Close to His heart

When the embrace was done,

Old Joseph said,

“How is Your Mother,

How is Your Mother, Son?”

My concluding comment on these poems is: memorize them! I can’t claim I’ve got them all memorized yet, but that is my goal. Memorization of poetry internalizes the art, and makes it “your own” in a way nothing else can: and you can draw on it at anytime, for your own delight and that of others.

For more great Catholic poetry, check out: “Anthology of Catholic Poets: 200 Years of Catholic Poetry in English,” compiled by Joyce Kilmer, and “The Catholic Anthology: The World’s Great Catholic Poetry,” edited by Thomas Walsh. Both have been republished by Os Justi Press.

If you enjoy my work here on my dad’s Tradition and Sanity Substack, please consider giving me a small tip via my buymeacoffee.com page, where you can make a one-time or recurring donation to support my writing. Thank you!

As a busy young mom, I used to type out a poem and tape it over the kitchen sink to memorize while I did the dishes. "Because housewives need well-furnished minds- we live in them so much" (Phyllis McGinley).

"A poem should be palpable and mute, as a globed fruit..."

"When I consider how my light is spent, ..."

"As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame..."

Thank you for reminding me of a happy past time, with this lovely article.

We memorized a poem every week in Jr. High English. Sr. Virginia would pick victims to recite it in front of class. We tried to be invisible. "O Captain My Captain our fearful trip is done..." Wiki hints Whitman had a boyfriend. What would Sr. Virginia say - gay is an adjective meaning merry. But that was long ago and far away.