Gregorian Chant: Music of the Holy Spirit (Part 1)

Only the eternal and infinite God could have begotten music of such perfection

Singing the Mystical Life of Christ

In a remarkable passage written in 1947, Dom Ludovic Baron describes the special assistance Almighty God must have given to the Latin Church in her centuries-long task of giving birth to the music that would adorn the Holy Sacrifice and the Divine Office:

If the Holy Ghost must aid in the accomplishment of the smallest good work, how much more must He have helped those who were to give this music its definitive expression in the liturgy! For this was precisely the objective of their efforts: from these texts, of which most were inspired in the highest sense, they must uncover the expression buried within, placed there by the Holy Ghost, and must specify it with a melodic formula that united the faithful in sentiment even as the words united them in thought. And this, not only for one part, for one Mass, or for one Office, but rather for the entire liturgy of the entire year. In a word, it was a matter of determining what the religious sentiment of the mystical life of Christ should be, day after day, and expressing it in a song that was capable of allowing anyone who sang it or heard it to enter into Christ’s interior disposition. One will easily admit that such a task exceeds the powers of the human mind and could only be accomplished with the assistance of the Spirit of Christ.1

In my experience of singing chant nearly every day of my life for over thirty years, and in the experience of the many singers I know who are familiar with this unparalleled and indeed astonishing repertoire, Dom Ludovic’s claim has been borne out again and again, as we see the “mystical life of Christ” reflected in and transmitted by a library of thousands of exquisite melodies.

In this two-part series (today and a week hence), I would like to offer many specific illustrations of the point made by Dom Ludovic. We’ll look at a number of Gregorian chants and see how eminently suited they are for divine worship and for their particular functions in the liturgy. And we’ll see how the chants are truly “musical lectio divina,” that is, prayerful meditation and mediation of the text in a musical mode. For each chant, I’ll include a recording.2 (The voiceover, accessible at the top of this post, incorporates the chant recordings as we go along with our commentary; the audio files are also given individually below, following each chant score.)

Reminder: Candlemas Special Offer

If you enjoy our work here at Tradition & Sanity, please take advantage of our special offer, which lasts until February 3:

“Hear, O Lord, my voice”

For most Sundays and Holy Days of my adult life, I’ve sung the Propers as part of a schola cantorum, that is, a choir specializing in Gregorian chant. Almost every Sunday, I find myself thinking: “Can the chants get any better than this?” And then I am pleasantly reminded that they are, as a rule, unbelievably spectacularly good — so varied in character, so subtle in word-painting, so melodically satisfying, so custom-fitted to their purpose, that it’s like a musical miracle. As Dom Ludovic says: for the Church to provide music worthy of the Holy Sacrifice, she must have received a special grace from the Holy Spirit. Those who know the chant have experienced this grace.

Plus, there’s what I call “God’s liturgical Providence,” a phrase I learned from a monk who was steeped in the Church’s lex orandi. How often does it happen that an antiphon, an oration, a reading, will be exactly what we needed to hear, whether personally or at a particular moment in the life of the Church on earth?

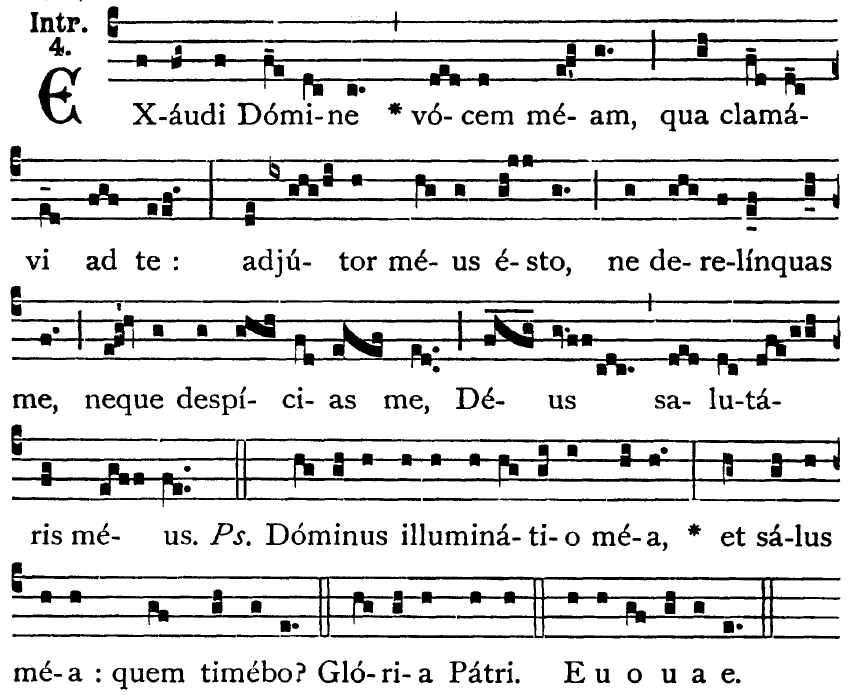

A case in point. It was the Fifth Sunday after Pentecost. The Introit’s intense text and unusual melody — mournful, restrained, almost exhausted — suited the discouraging rumors about new Roman crackdowns on the TLM that had burdened us all week.

Hear, O Lord, my voice with which I have cried to Thee: be Thou my helper, forsake me not, nor do Thou despise me, O God, my Saviour. Ps. The Lord is my light, and my salvation, whom shall I fear? V. Glory be to the Father...

These are the mingled sentiments of Roman Catholics who love their own tradition: the fear that it may be taken away; that we may be forsaken and despised; a plea that God will hear us and help us; a constant faith that, in spite of everything, He is our light and our salvation, who banishes fear. To Him, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, be glory for ever and ever.

The sole and rather vulnerable high point is on the word “esto”: BE thou my helper! The use of the ‘te’ (flattened seventh note in the scale) on “adjutor” makes the ‘ti’ (the natural seventh note) on “illuminatio” stand out all the more brightly, like a ray of light piercing the darkness.

“That I may dwell in the house of the Lord”

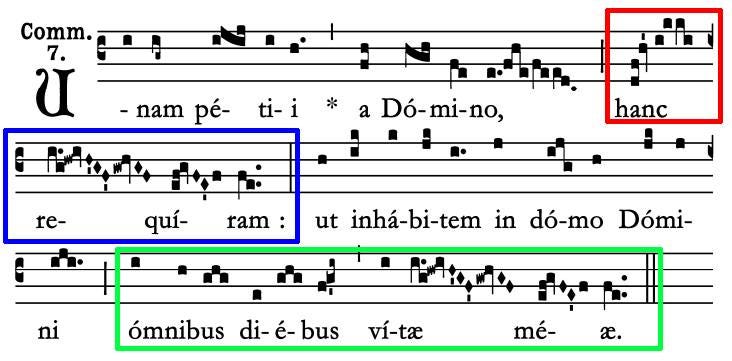

On the same Fifth Sunday after Pentecost, we should take a look at the Communion antiphon: “One thing I have asked of the Lord, this will I seek after: that I may dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life.” Of the many features one could point out even in this simple antiphon, here are a few that catch our attention.

1. The word “Domino/Domini” is treated very nicely in two very different ways: the first time low a nd slow, the second time high and swift: as if the soul needs to start humbly, in the lowly posture of one petitioning the mighty, before expressing her full confidence that her petition will be granted.

2. The phrase in red, simply the word “THIS,” is the melodic figure that stands out the most, and appropriately so: THIS will I seek after; THIS is the summation of all desires. As St. Augustine says: “What is a life of happiness but what all men want, what man cannot not want?”

3. The phrase in blue, the word “will I seek,” is spun out in a lengthy gradual descent — a musical likeness to the activity of seeking long and hard until one finds what one is seeking for: “What woman having ten pieces of silver, if she lose one piece, doth not light a candle, and sweep the house, and seek diligently till she find it?”

4. The phrase in green, which concludes the chant, is (especially if sung as a single phrase, on the one “collective breath” of the schola) a marvelous depiction of the spaciousness of eternal life. It’s not only the text that’s saying “all the days of my life”; the melody communicates it too. And note the subtle touch: the melody of “vitae meae” is identical to that of “requiram.” It’s the answer, so to speak, to the prayer: what I seek is to dwell in the Lord’s house for ever. And there I shall rest, even as the chant comes to a gentle rest.

Sheer artistic perfection. Unsurpassable, really. Polyphony is wonderful, but the chant sets the Word of God with a finesse that nothing else rivals. And that is why (to quote the Second Vatican Council) “the Church recognizes Gregorian chant as proper to the Roman liturgy: and, therefore, in liturgical actions, it must, other things being equal, hold the chief place.”3

Petitioning with humility

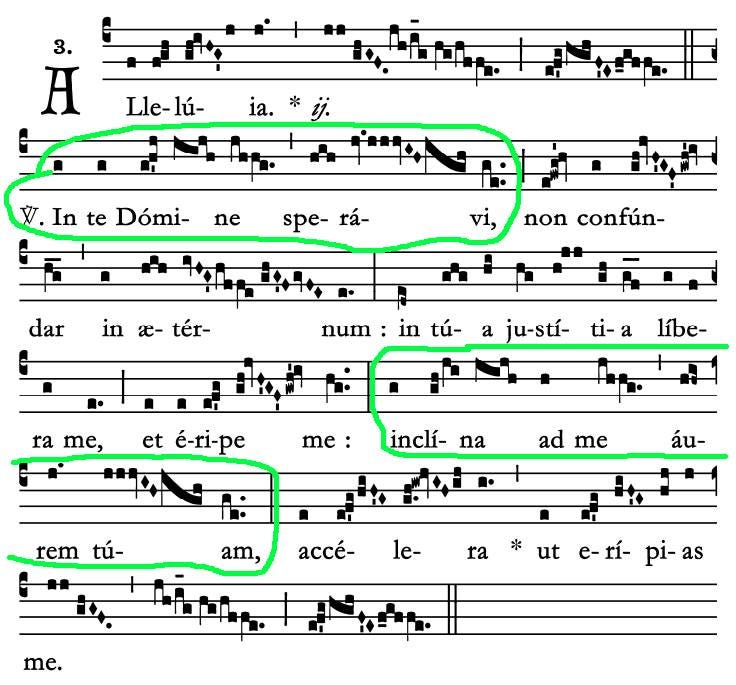

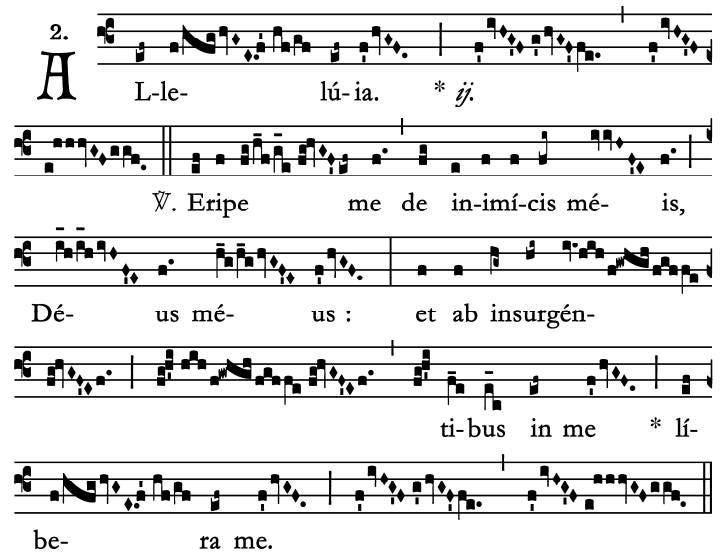

The Alleluia for the Sixth Sunday after Pentecost is a marvelous composition. (As an aside: mode 3, perhaps more than other modes, really brings out how very different chant is from the diatonic music we’ve grown accustomed to.)

Of the many beauties of this antiphon, I will point out only one: the repeated figure, circled in green, on “In te Domine speravi” (in Thee, O Lord, have I trusted) and “inclina ad me aurem tuam” (incline Thine ear to me), which musically depicts the prostration of the suppliant, the one who comes before his master begging for a favor or for a hearing. Look at how the arc of the melody starts high, and then declines like a bow:

This chant reminds me of the words of St. Benedict: “When we wish to suggest our wants to persons of high station, we do not presume to do so except with humility and reverence. How much the more, then, are complete humility and pure devotion necessary in supplication of the Lord who is God of the universe!” (Holy Rule, chapter 20). You can see this humility in the bowing of the Old Covenant . . .

. . . of St John the Baptist . . .

. . . and of the priest at the Holy Sacrifice.

Showing the Unity of the Covenants

This mention of the priests of the old covenant, of John the Baptist who straddles the covenants, and of the ministerial priests of the new covenant brings to mind one of the most admirable features of the classical Roman Rite, namely, how tightly it connects the Old and New Covenants, in ways both obvious and subtle — in the formulation of prayers modeled on OT prayers, in gestures that have OT parallels, in the choice of texts to be sung, most of which are from the psalms, but understood in their spiritual sense as allegories of Christ. The TLM emphasizes the continuity of the Old with the New, even as it points to the superabundant fulfillment of the former in the latter. All this is quite muted in the modern rite of Paul VI — a fact that has huge theological implications. But I will not go into those at the moment.

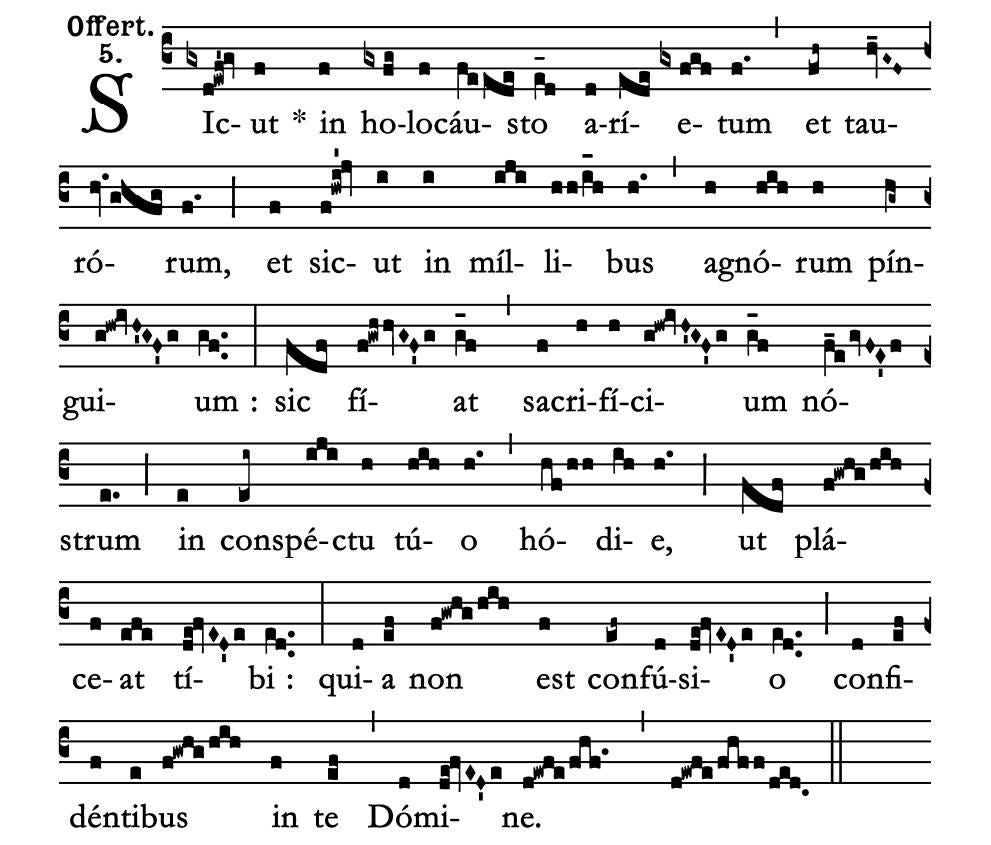

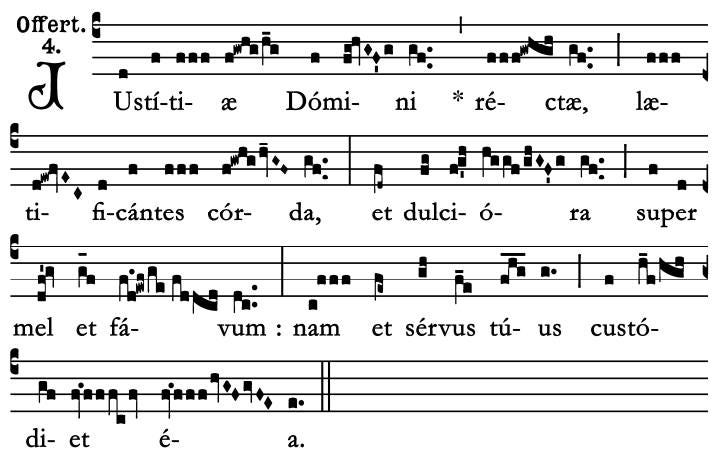

The Seventh Sunday after Pentecost offers a beautiful juxtaposition of just this kind. The Offertory antiphon, from the book of Daniel, alludes to King Solomon’s gigantic sacrifices, which accompanied both the inauguration of his reign and the dedication of the Temple.4 The Secret then shows the allegorical meaning by explicitly pointing the old sacrifices to the once-for-all supreme sacrifice of the Cross, elegantly tying in a mention of Abel as well, who will soon be mentioned in the Roman Canon.

Offertory Antiphon (Dan 3:40):

As in holocausts of rams and bullocks, and as in thousands of fat lambs; so let our sacrifice be made in Thy sight this day, that it may please Thee: for there is no confusion to them that trust in Thee, O Lord.

Secret prayer:

O God Who, in this one sacrifice, hast perfected the offering of the many victims prescribed under the Old Law: receive this same sacrifice offered by Thy devoted servants and sanctify it with a blessing, like unto that which Thou didst bestow upon the offerings of Abel; so that what each has offered here to the glory of Thy name, may profit all unto salvation. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, Thy Son, who liveth and reigneth with Thee in the unity of the Holy Ghost, world without end. Amen.5

The TLM’s “Jewishness” witnesses to the unity of salvation history by confidently and frequently employing old covenant language and symbolism, precisely because Christ is the heir of all the promises to the patriarchs, the seed of Abraham, the son of David, the new Adam; He was the one whom Israel was predestined to foreshadow and prepare. All the “Great Adventure” and “Father Who Keeps His Promises” stuff came alive for me when I began to pay attention to the texts and ceremonies of the TLM. In short: the Mass of the Ages speaks with and on behalf of Israel because it is unabashedly supersessionist in its theology. It simply is the worship of the divinely-revealed Hebrew religion transposed into a universal messianic key, and therefore appropriately enriched with Greco-Roman and Franco-Germanic elements.

The Romans Closing In

Ancient pagan Rome was one of several instruments by which Divine Providence effected the transition from old-covenant temple worship to the once-for-all sacrifice of Christ on the Cross renewed in every Mass. This played out in many ways and on levels from local to universal. First, Pontius Pilate had to be who he was and where he was in order to fulfill the prophecies about the Messiah, thus inaugurating the new Israel. Second, the Romans had to be who and what they were in order to put down the Jewish Revolt in AD 70 and pulverize the Herodian Temple into dust, marking the decisive end of the Old Covenant religion and the commencement of its rabbinical simulacrum. Third, the Romans built the greatest empire known to man, and paved roads everywhere so that the messengers of the Good News could reach the ends of the earth. Fourth, drawing heavily on the Greeks, the Romans achieved a high level of civilization, which was a prerequisite to the formation of the liturgy, creeds, and art forms of Christendom.

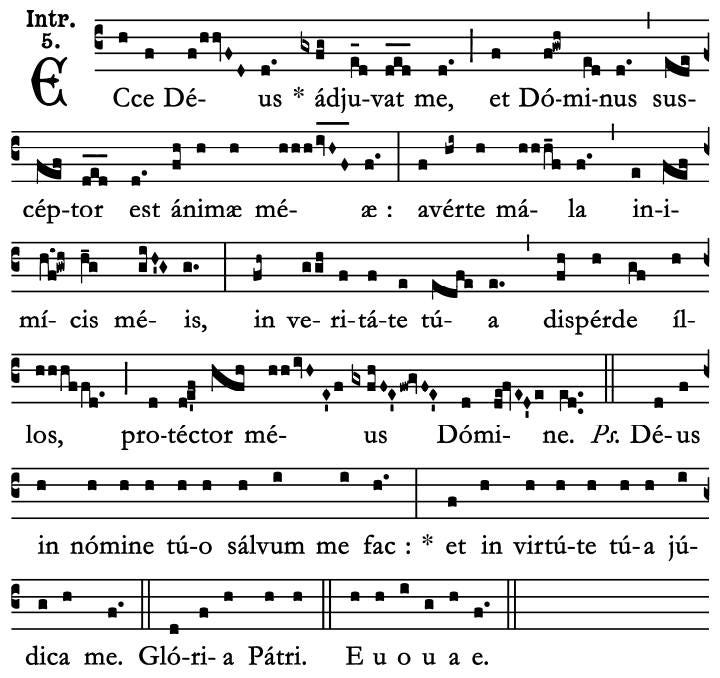

If we turn to the Proper chants for the Ninth Sunday after Pentecost, we can catch another glimpse of this OT/NT connection.

Normally, chants feature wide-ranging melodies. Occasionally, you’ll have one with a very limited range. But you almost never get multiple chants of that character in a single Mass. On this particular Sunday, it is different. The Introit and Offertory both feature melodies confined to 6 notes; the Alleluia is confined to only 5 notes (with a single “grace” note that dips outside). The Gospel of the day is the prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem. Note what the Lord predicts: “For the days shall come upon thee, and thy enemies shall cast a trench about thee, and compass thee round, and straiten thee on every side...” The verb for “straiten” is coangustare, which means: confine to a narrow space, cramp, make narrower, narrow or limit the scope or application.

Well, how about that? Three of the five proper chants are confined to a narrow space, cramped, limited — even as Jerusalem will be at the hands of its enemies in AD 70.

Now, I’m not saying that anyone (let alone any committee!) had this parallel between the Gospel and the Propers specifically in mind. But the eternal God had it in mind, and arranged that these chants should, even literally, reflect the frightening message of both the Epistle and the Gospel. If you look at the texts of the Introit & Alleluia, you will see people crying out for help against their enemies. There is a parallel here: we can imagine ourselves as under siege by the world, the flesh, and the devil, and we beg the Lord to deliver us from our enemies, instead of delivering us to them on account of our sins.

Candlemas

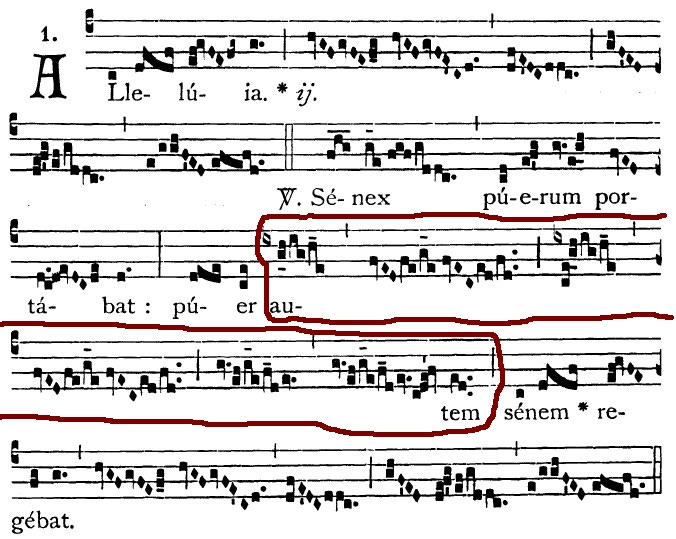

Fittingly enough for this time of year, let’s take, as our last example, the Alleluia for Candlemas, a.k.a. the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary or the Presentation of the Lord. This Alleluia features one the greatest extended single-syllable melodies of the entire Gregorian year (such a melody is technically called a melisma).

The text has always been a favorite of mine:

Alleluia, alleluia. V. Senex Púerum portábat: Puer autem senem regébat. Alleluia. (V. The old man carried the Child: the Child, however, governed the old man.)

Here is how the music emphasizes the unexpected divine twist:

Treasures as far as the ear can hear

All the sorts of things I’ve discussed today could be multiplied endlessly, across the entire Church year, for every Sunday, every feast, every season. The Proper chants are especially rich in musical depictions of the literal and spiritual senses of Scripture, but the chants of the Ordinary of the Mass are no less ingenious, no less saturated with theological meaning. I have to repeat this point in the hope that it will stick: the traditional music itself is theologically charged, united in a one-flesh marriage with the texts. And I say about this marriage what Our Lord said about matrimony: what God hath joined together, let no man put asunder.

We’ll resume next week with examples from Advent, Eastertide, Corpus Christi, and the month of November.

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you.

For a limited time (through February 3), get 25% off a paid subscription to Tradition & Sanity:

L. Baron, L’expression du chant grégorien. Commentaire liturgique et musical des messes des dimanches et des principales fetes de l’année I (Plouharnel / Morbihan: Abbaye Sainte-Anne de Kergonan, 1947), xxvi, quoted by Michael Fiedrowicz in his peerless introduction to the classical Roman Rite.

Usually sourced from the remarkable Saint René Goupil Gregorian Chant Propers of Corpus Christi Watershed.

SC 116: “Ecclesia cantum gregorianum agnoscit ut liturgiae romanae proprium: qui ideo in actionibus liturgicis, ceteris paribus, principem locum obtineat.” I’ll admit that Garrett Meyer makes a fine case for the internal contradiction introduced by the phrase ceteribus paribus or “other things being equal.” Still, the authors of this provision believed that they were asserting the primacy of chant.

Part of this verse, of course, also shows up at every Mass in the Offertory, in the prayer right after the offering of the wine: “In spiritu humilitatis et in animo contrito suscipiamur a te, Domine, et sic fiat sacrificum nostrum in conspectu tuo hodie, ut placeat tibi, Domine Deus.”

Fortunately, this oration was part of the 13% of the euchology of the old missal that was retained unchanged in the Missal of Paul VI, where it appears under the “16th Sunday Per Annum” — but, alas, torn out of its original context with the required Offertory chant, Offertory prayers, and Roman Canon, which is the other famous mention of Abel in the Mass.

Excellent point regarding the "Jewishness" of the liturgy. It's curious. The liturgical reformers in many respects wanted the liturgy to be more "Jewish" -- but, ultimately, what they produced is less "Jewish," crudely transplanted table blessings notwithstanding. One need look no further than the feast of the first day of the (civil) year, as it appears in the two dispensations. But the same reality is evident all over the place. One sees a direct line between "Temple" and "Church" at the TLM; at the NO, there is barely a line between "Synagogue" and "Church."

"It simply 𝘪𝘴 the worship of the divinely-revealed Hebrew religion transposed into a universal messianic key, and therefore appropriately enriched with Greco-Roman and Franco-Germanic elements"—what a superb summation of the thoroughly biblical, transhistorical, transcultural, all-encompassing spiritual-artistic glory of the traditional liturgical rites of western Christendom. If only the 1960s "reformers" had realized that in attempting to greatly improve upon these rites, they were attempting something that was—especially for modern man—utterly impossible.