Gregorian Chant: Music of the Holy Spirit (Part 2)

How the Church, a master of human psychology, marks times and connects the times through her chants

Today, we continue our exploration of the inexhaustible riches of Gregorian chant — always in reference to specific examples, as generic praise goes only so far. What I want to show is the divine in the details. As with part 1, I’ll provide the best recording I can for each example (adding up, altogether, to about 20 minutes’ worth of gorgeous chant to listen to as we go along).

Marking time

Psychologists have studied how music penetrates into the memory much better than mere text, and how repetition strengthens the memory. The Church, the master psychologist, understood this ages ago, by assigning certain melodies to certain days of the liturgical year, in a manner that was utterly fixed, so that every year (or, in some cases, as with the feasts of Apostles, many times a year) certain chants would be associated with certain mysteries of Our Lord or Our Lady, with saints and seasons. In this manner, the chant repertoire clearly and memorably marks days and seasons of the liturgical year.

For example, nothing says “Advent” like the soaring melody of “Ad te levavi,” the Introit of the First Sunday of Advent. This chant has been part of my life for decades, but it’s been in the liturgy of the Western church for well over a thousand years. Here’s a picture of it in the famous St Gallen MS 359 (ca. AD 925), in the original “neumes” prior to the invention of square notes:

and then, in the Liber Usualis from which scholae cantorum sing today:

To Thee have I lifted up my soul: in Thee, O my God, I put my trust, let me not be ashamed: neither let my enemies laugh at me: for none of them that wait on Thee shall be confounded. Ps. Show me, O Lord, Thy ways: and teach me Thy paths. V. Glory be to the Father…

Connecting times

But the chant does more than mark days or seasons. It also makes subliminal connections between them. The chant melody used in the Alleluia for Gaudete Sunday is the same as that used for the first Alleluia on Pentecost Sunday. In both, the verse begins with a plea to the Father: “EXCITA” (stir up) and “EMITTE” (send forth). In both, salvation is the grace besought: “come to save us” and “thou shalt renew the face of the earth.”

In Advent, this is a plea for God to intervene, and He does by sending His Son. At Pentecost, the plea for God to intervene is renewed, and He responds by sending His Holy Spirit. What is begun in Advent is fulfilled at Pentecost: the “promise of the Father” is, first, the Messiah and Redeemer, and ultimately, the gift of the Holy Spirit that makes us sons in the Son.

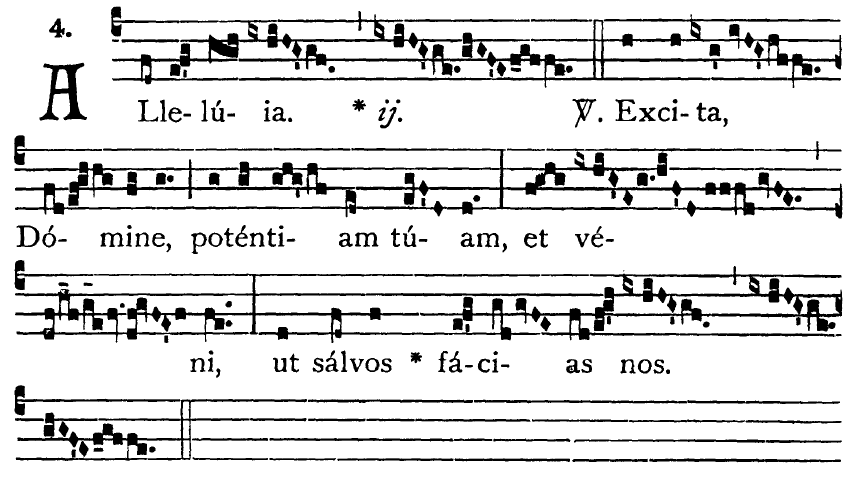

Gaudete:

Alleluia, alleluia. V. Stir up, O Lord, Thy might, and come to save us. Alleluia.

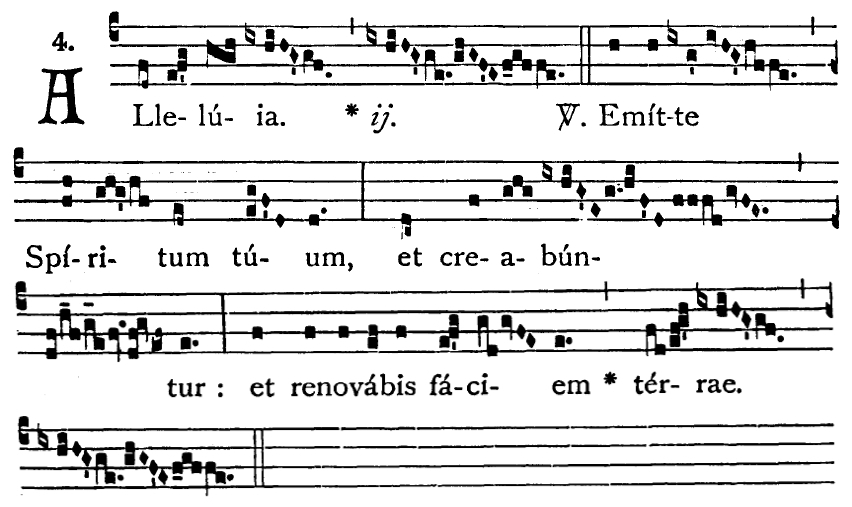

Pentecost:

Alleluia, alleluia. V. Send forth Thy Spirit, and they shall be created, and Thou shalt renew the face of earth.

In The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals, an extraordinary book edited by Joseph Shaw, we learn that modern artists before the Council were intrigued with the “newly-discovered” subconscious realms in the soul, and some of them recognized that the Church had already figured this out — not systematically but experientially — in her rites, devotions, symbols, artworks. Using the same melody on Sundays very far apart in the liturgical year (almost as far apart as they can be) is not an obvious “hit you over the head” kind of thing but a subtle connection that is internalized over many years of attending sung Mass. Your conscious mind isn’t necessarily making a conceptual link, but this unforgettable melody has gone into your soul year after year, and there’s an awareness being forged of the connection between the Redeemer and the Sanctifier.

One could point to thousands of examples of how the old rite works this way, especially in its sung form. An absolute marvel of artistry guided by Divine Providence. Think of the whole-person formation that would be received by always attending the sung Mass, week after week, year after year! Think of the even deeper formation a monk or nun would receive by chanting this liturgy daily over the course of decades. No wonder our most profound commentaries on liturgy and the Scriptures come from people who did exactly this.

How beautiful, how refined, is the Roman Rite in its bimillennial arc of development!

Corpus Christi

On the feast of Corpus Christi, the Roman Rite does something very subtle. When the Propers were composed for the feast — by none other than St. Thomas Aquinas! — the melodies of the Offertory and Communion were adapted from other chants, as often occurs with feasts introduced later on. So, which melodies were chosen as the models? Those from Pentecost Sunday. Thus, “Sacerdotes Domini” takes the melody of “Confirma hoc,” and “Quotiescumque” takes the melody of “Factus est repente.”

As before with the Gaudete/Pentecost connection, I maintain that this move reflects a deliberate strategy — a fact that becomes apparent when you examine the new texts being set to the older melodies. The use of the same (very distinctive) melodies forges a theological association between Pentecost and Corpus Christi, and over time, reinforces it psychologically for worshipers who regularly attend sung Mass.

Let’s have a look at this pair of pairs.

Offertory antiphon for Pentecost:

Confirm, O God, what Thou hast wrought in us; from Thy temple, which is in Jerusalem, kings shall offer presents to Thee. Alleluia.

Offertory antiphon for Corpus Christi:

The priests of the Lord offer incense and loaves to God, and therefore they shall be holy to their God, and shall not defile His name. Alleluia.

Both of these are about offering gifts in the temple. The Spirit of holiness is the one who makes holy the kings and the priests (since Our Lord is both High Priest and King of Kings); and we need Him to confirm what He works in us lest we defile His name, since our bodies are His temple, and they will receive His Body.

Communion antiphon for Pentecost:

Suddenly there came a sound from heaven, as of a mighty wind coming where they were sitting, alleluia; and they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, speaking the wonderful works of God. Alleluia, alleluia.

Communion antiphon for Corpus Christi:

As often as you shall eat this Bread and drink the Chalice, you shall show the death of the Lord until He come: therefore whosoever shall eat this Bread or drink the Chalice of the Lord unworthily, shall be guilty of the Body and Blood of the Lord. Allelluia.

The sound that comes from heaven can be taken as a symbol of the Word that comes forth from heaven; those who are sitting, so to speak, at the table of the Lord and drink from the chalice of Communion are filled with the Holy Ghost. If they are well disposed, God’s most wonderful work is done within them, as they are conformed to His death that brings life; while if they are badly disposed, He is, as it were, killed by them anew and further expelled from them.

The most basic lesson taught by this pair of fraternal Communion chants is that the primary way to receive the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Jesus Himself, is to feast upon His holy and life-giving flesh, the Bread that comes down from heaven, filled with His Spirit — not through seeking charismatic graces or emotional satisfactions or outgoing activities. “It is the spirit that quickeneth: the flesh profiteth nothing” (Jn 6:64), that is, the spirit of Christ alive in His glorified Body, made present to us in the Holy Eucharist.

This is a brilliant example of why I say (and others have said) that Gregorian chant is “musical lectio divina.” It does not merely clothe the texts with music, it interprets them, weaving together various strands of revelation. Chant is a lifelong course in ascetical-mystical theology.

And while it’s true that the lectio divina pays off the most for those who are paying attention, who are gathering experience and reflecting on it, the wonderful thing is that these liturgical associations have a way of working subconsciously or subliminally as well, given enough exposure. The faithful who hear the chants year after year will have feelings and thoughts stirred up by this or that chant and they might not even realize why it’s happening! But the Spirit of God who inspired His human collaborators knew what He was planting in the liturgy, where, and why. His thoughts go beyond our thoughts and guide them. More than once, I’ve had the experience of thinking a certain thought or line of thought, and then realizing subsequently that it was prompted by a connection like this, of which I wasn’t even initially aware.

Another sign of the wisdom of Holy Mother Church: She has us celebrate Corpus Christi on a Thursday, as a direct reminiscence of Maundy Thursday but far removed from the sorrowful confines of the Triduum; and then she allows us to celebrate it again on Sunday as an “external solemnity.” At my FSSP parish, I was able to sing for a Solemn Mass on Thursday, and then again for a Sung Mass on Sunday — with all the joy, and power, of repeating something eminently worth repeating. One can bask in it.

It’s this kind of repetition that makes a person start thinking, for example, about things like the melodies of the chants, which is what led me to realize the connections I’m sharing with you now. This wasn’t something I read about in a book. It was something I discovered through experience. Repetition is vastly more important than we give it credit for being. The Church led by the Spirit of God knew and knows this; the quasi-schismatic simulacrum that substitutes for the Church in our times does not know it; denies it; undermines it. By their fruits ye shall know them.

Rejoicing in hope

One of the things I found most striking when I first came into tradition decades ago is the double Paschal Alleluia.

Starting on Easter Saturday and running for the whole of Paschaltide, the authentic Roman Rite features not one, as usual, but two melismatic1 Alleluia chants between the Epistle and the Gospel, in place of the usual Gradual/Alleluia combo (or Gradual/Tract on penitential days or in penitential seasons). The second Alleluia proper follows immediately upon the first. Thus, the key biblical word of praise will be sung, at glorious length, four times, reminiscent of the four Gospels by which the victory of Christ is proclaimed, and the four corners of the world to which their sound has gone out (cf. Ps. 19:4), and from which the angels will gather the elect (cf. Mt 24:31).

In this way Holy Mother Church erupts with a heavenly song of joys that stretch far beyond this world and into the courts of the risen King. The jubilance, spaciousness, and exultation of these melodies (in both Alleluia and accompanying verse) is second to none; they are among the most glorious ever composed by mortals.

In spite of a residual presence in the rarely-used 1974 Graduale Romanum,2 all this heritage was effectively chucked out the wide-open window after Vatican II, replaced by trivial jingly ditties at the so-called “Gospel acclamation,” for the sake of so-called “active participation.” Yet another short-sighted move that took away from the faithful the contemplative joy unfurled by the Alleluias of our Latin-rite tradition, familiar to untold generations of monks, nuns, canons, clergy, and faithful, wherever the Mass was chanted.

It was the interlectional (in-between-the-readings) Alleluias that first taught me the full magnitude of the ALLELUIA — praises lifted up to the Lord on high — as it resounds in the sacred liturgy as elaborated by the Holy Ghost over the centuries of faith. We earthborn mortals need this uplifting, celestial chant.

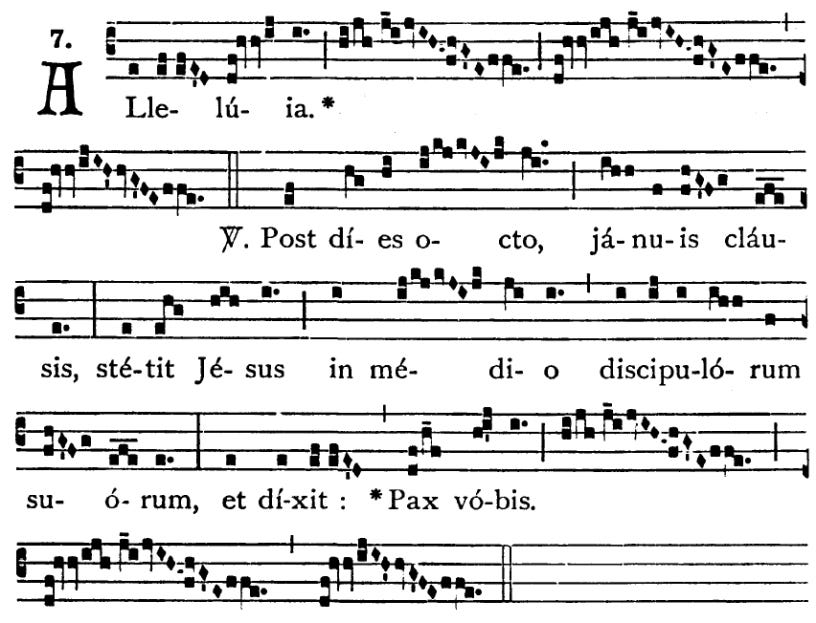

Alleluia, alleluia. V. On the day of my resurrection, saith the Lord, I will go before you into Galilee.

Alleluia. V. After eight days, the doors being shut, Jesus stood in the midst of His disciples, and said: Peace be to you. Alleluia.

Although I initially said there would be two parts, I’ve realized that I have quite a bit more to say, so I’ll allow myself a third part (and maybe more, we’ll see). In Part 3, we’ll continue with more examples, as well as some broader considerations about Gregorian chant in the Church today.

Thank you for reading Tradition & Sanity, and may God bless you!

P.S. Here I am with the local schola, singing on Palm Sunday some years ago:

The word “melismatic” refers to lengthy, elaborate melodies on syllables. The melisma on the final “a” of the alleluia has a special name: the jubilus.

Residual in the obvious sense: by 1974 the horse was out of the barn and almost no one was singing chant anymore, urged on (of course) by Paul VI telling everyone in November 1969 that the Church was making the enormous sacrifice of Latin AND chant for the sake of apostolic outreach to modern people. So its presence is a residue from the past, but with little current relevance, outside of Solesmes and the rare hot spots that do the Novus Ordo contrary to the mind of its legislator.

Everything you write about repetition over the years is so true. I sang in a scholarly for 4 years and I found that, having sung it the first year, the same chants would arrive again the next year and became familiar friends. But the wonder of their meaning and appropriateness became deeper. It’s as if these chants became interiorized with greater meaning with each passing year. It really is a wonder.

Thank you for sharing the music along with the article. Can the music shared with us be accessed/purchased in a single recording?