Gregorian Chant: Music of the Holy Spirit (Part 3) + List of Resources

Further examples of the perfection of this ideal liturgical music — and recommended websites for instruction, recordings, and scores

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, I went into some detail to show how admirably suited Gregorian chant is to clothing in music the divine and human words out of which the liturgy is composed. Today I would like to offer more examples of the same, along with a handy list of free resources. (While I hope you will look back at Parts 1 and 2, reading them is not presupposed to reading this one.)

Palm Sunday

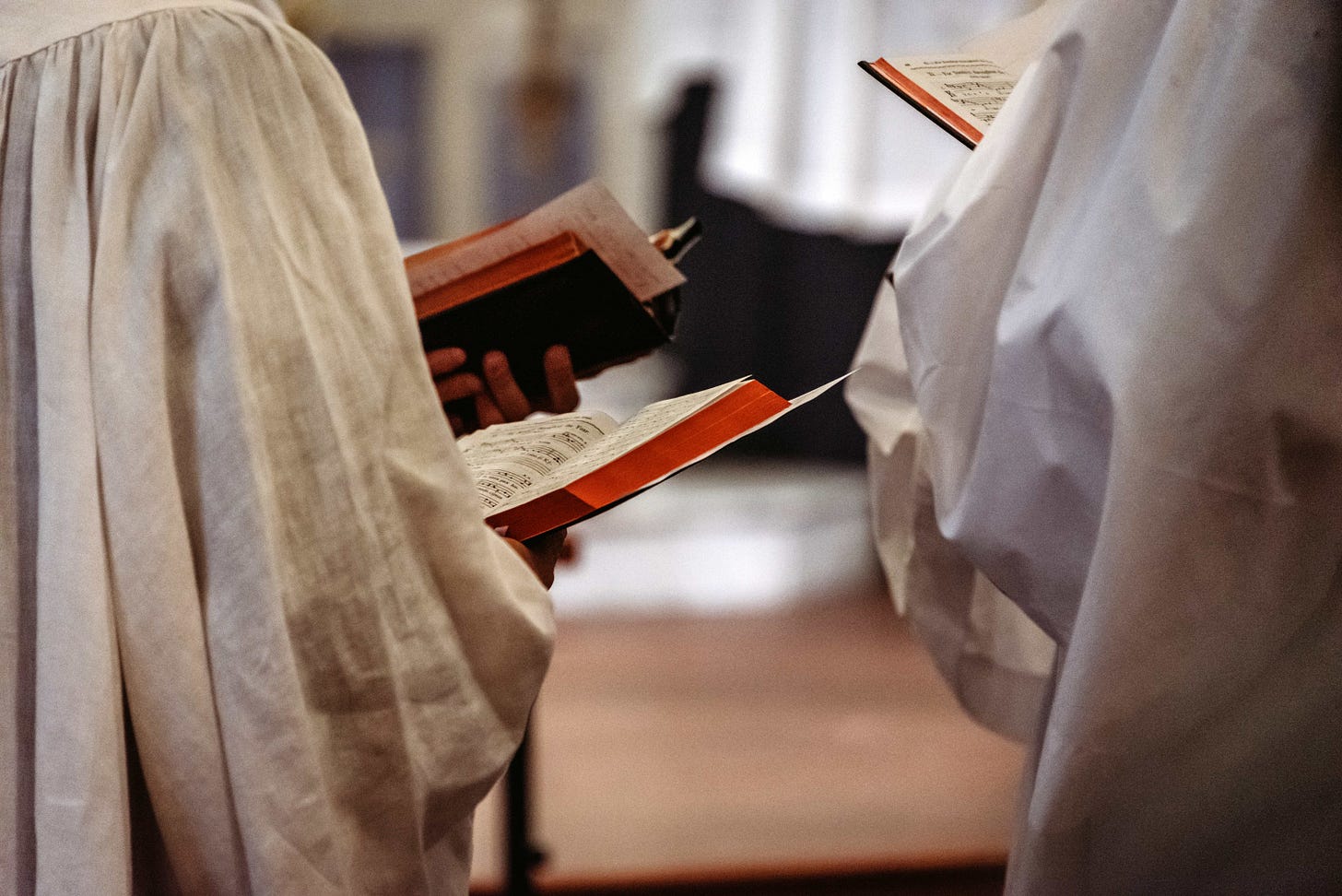

As we approach the start of Holy Week, it seems appropriate to open a window into the extreme antiquity of one of the most popular chants of the Church year: “Hosanna filio David,” sung at the start of the liturgy of the Second Sunday of Passiontide (familiarly called Palm Sunday).

When we are singing chant, we are not singing something invented whole cloth in the Middle Ages. We are singing a music that emerged in ancient times out of a confluence of Hebrew, Greek, and Roman musical traditions. We are, in that sense, bringing to God the ripest cultural fruits of Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, in service of the transcendent Beauty we worship.

Here is what we learn from music scholars:

“Hosanna filio David” is traditionally performed in Gregorian chant, characterized by its monophonic melody and free rhythm. The chant is simple yet solemn, designed to enhance the liturgical action without overshadowing it. Scholars have noted the close relationship of this melody with the melody of the Seikilos epitaph, the oldest surviving piece of music, but where the long notes are resolved by groups of simple beats.

Only one explanation is plausible: the Greek melody will have given rise to a citharodic variation, where this resolution of long values was the rule; preserved in the repertoire of instrumentalists, with its title alone, it was used by the centonisator of the Hosanna antiphon, to whom the rapprochement of Hoson and Hosanna will have given the idea of using the ancient theme. Its melody, preserved in medieval manuscripts such as the Graduale Romanum, reflects the jubilant yet reverent spirit of Palm Sunday.

Exalting God’s commandments

In order to help clarify why chant is the right way to clothe the texts of the liturgy, we must ask how the form of our worship should relate to the content of Scripture and to its purpose—including our awareness of its purpose.

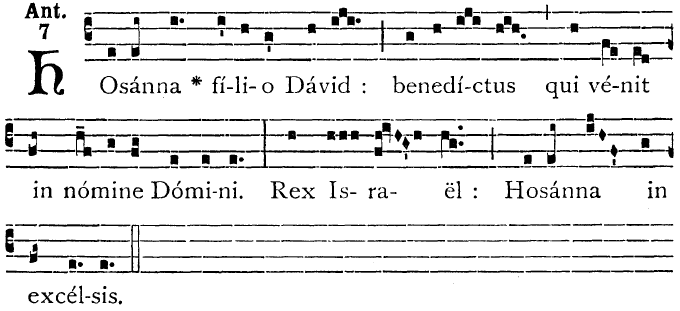

The Second Sunday of Lent features a magnificent Offertory antiphon, with a gorgeous melody, whose text was instrumental in changing the way I thought about the role of Scripture in the Mass. The text is from Psalm 118, vv. 47-48: “I will meditate on Thy commandments, which I have loved exceedingly: and I will lift up my hands to Thy commandments, which I have loved.”

As I reflected on these words, three things occurred to me.

1. We are to meditate on the Word of God. Thus, a form of liturgy that has Scripture integrated into it all over the place (and not just in a lectionary)—that repeats passages annually or even more regularly (think, e.g., of Psalm 42 or the Last Gospel) and gives us “room” in silent prayer to ponder the words—is a liturgy that will enable us better to “meditate on Thy commandments.”

2. We are to “love exceedingly” the commandments. The emphasis is placed on the kindling of desire to receive, venerate, and follow God’s word. Thus, a form of liturgy that maximizes and multiplies signs of reverence toward God’s words—indeed, toward the very books in which God’s words are written—will be better at awakening awareness of the mystery we are facing and at kindling desire for it. Anyone who has seen how Scripture is treated in the old rite, especially in the solemn high Mass, will know what I am talking about.

3. Finally, “I lift up my hands to Thy commandments.” This helped me to realize that the proclamation of Scripture at Mass is not merely informative or didactic; it is in fact a form of worship directed to God Himself. We read His words not only to learn, but even more to honor the One from whom they come, the One to whom they return in our chanting. It’s almost as if the text here depicts God’s commandments in heaven: they are way up there, so to speak, and we lift our hands to them, being drawn up into God by them. This is why St. Thomas Aquinas can say, rather strikingly, that it matters more than the faithful know WHY the words are being chanted, namely for God’s glory, than what exactly they are saying (see ST II-II, Q. 91, art. 2, ad 5).

This is what I’m getting at in my recent book Turned Around (p. 139):

The solemn and formal style of the readings as done in the TLM, directed elsewhere than the people immediately present—the Epistle is read toward the east, and the Gospel toward the north—makes it clear that we are acknowledging that the God whom these texts mention is really here in our midst, or rather, we are come into His presence with thanksgiving; thus, the readings turn into gifts that, having been placed in our hands by God, we turn around and offer back to Him, even as we do with the bread and wine. Or to use a different metaphor, the readings are a form of verbal incense by which we raise our hands to His commandments.

I can’t begin to say how much the experience of the old Mass rejuvenated and energized my relationship to the Bible. Gregorian chant, as a part of that experience, played a pivotal role in this regard, for it taught me how special, how unique, is the word of God, how much it should be honored and dignified by the music that dares to take it up.

From a barbarous people

Moreover, to grasp the perfection of chant, which is always in service of God’s word and in alignment with the Church’s teaching and mission, we must consider the range and message of the texts.

The old rite’s lex orandi or law of prayer confronts the faithful with “uncomfortable truths,” often very anti-modern; and by chanting them, often slowly, it underlines them all the more. It does this not to be provocative, as a modern art installment might be, but simply because it calmly reflects the full message of divine revelation and always has. The new rite, as authors like Lauren Pristas and Matthew Hazell have well documented, removes or downplays much of this “difficult” content, and does so on purpose, because of the optimistic and humanistic spirit of the 1960s in which it was born.

We can find illustrations of the vigorous and realistic lex orandi of the old rite by opening up the missal anywhere and letting our eyes run across what we find. Here are several examples from the 21st Sunday after Pentecost.

INTROIT. All things are in Thy will, O Lord; and there is none that can resist Thy will: for Thou hast made all things, heaven and earth, and all things that are under the cope of heaven: Thou art Lord of all. Blessed are the undefiled who walk in the way: who walk in the law of the Lord. (Esther 13:9–11)

The Introit asserts the supremacy of God’s will. No one can resist Him. Indeed, man’s fundamental inclination for happiness is not subject to choice but is a natural necessity. Yes, sinners may resist Him for a time, but they are, as it were, hurling themselves against a stone wall. He is the Creator of all things in heaven and on earth, contrary to modern pseudo-scientific materialism. And those who are blessed are blessed because they follow His law. This Introit is a summation of anti-liberalism.

EPISTLE. Brethren: Be strengthened in the Lord, and in the might of His power. Put you on the armour of God, that you may be able to stand against the deceits of the devil. For our wrestling is not against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers, against the rulers of the world of this darkness, against the spirits of wickedness in the high places. Therefore take unto you the armour of God, that you may be able to resist in the evil day, and to stand in all things perfect. Stand therefore having your loins girt about with truth, and having on the breastplate of justice, and your feet shod with the preparation of the gospel of peace, in all things taking the shield of faith, wherewith you may be able to extinguish all the fiery darts of the most wicked one. And take unto you the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God. (Ephesians 6:10–17)

Here the devil and the other evil spirits come clearly into focus, reminding us that our warfare is primarily spiritual, not carnal, although the world and the flesh are the battlefield. This is a perfectly anti-naturalistic, anti-humanistic, anti-synodal message. (I say “anti-synodal” because it is the Word of God that is the sword of the Spirit, not the bloviations of committtees yammering about modern needs and how we need to modify our doctrine based on personal experiences, etc.)

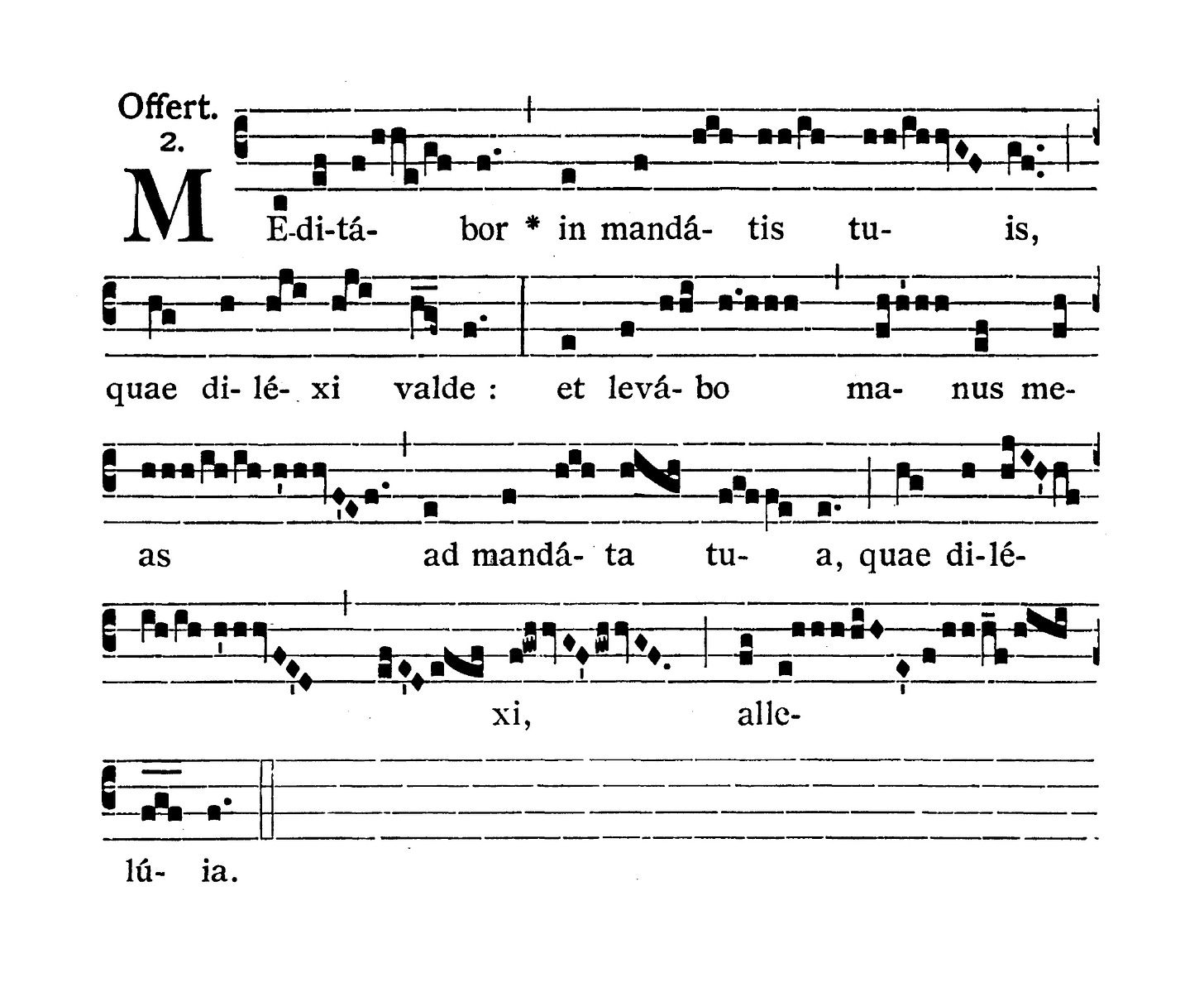

ALLELUIA. Alleluia, alleluia. When Israel went out of Egypt, the house of Jacob from a barbarous people. Alleluia. (Ps 113:1)

The Alleluia verse (not even a complete sentence!) is one of those delightful shockers. The Lord is telling us that it doesn’t matter how sophisticated Egyptian civilization was, or, for that matter, how brave a new world Western modernity has built for itself; if we don’t worship the true God and follow His law, we are barbarous. Any pagan or man-invented religion is barbarous compared to the true religion. This is a perfectly anti-interreligious message, delivered to the era of Pachamama, Abu Dhabi, and Singapore.

GOSPEL [the end of it]. And his lord being angry, delivered him to the torturers, until he paid all the debt. So also shall my Heavenly Father do to you, if you forgive not every one his brother from your hearts. (Mt 18:35)

This is not a nicey-nicey message about a God who pampers us with prosperity and pats us on the head to say “Good little saints.” If we do not model our attitudes and behavior on those of Christ, we will be delivered to the torturers, either for a time in purgatory or for ever in hell. A perfect missile launched against Moral Therapeutic Deism.

OFFERTORY. There was a man in the land of Hus, whose name was Job, simple, and upright, and fearing God: whom Satan besought that he might tempt: and power was given him from the Lord over his possessions and his flesh; and he destroyed all his substance and his children; and wounded his flesh also with a grievous ulcer. (cf. Job 1)

These words, adapted from the book of Job, continue this tough-love message. God loves us, yes, but He also tests us and purifies us as gold or silver in the furnace. The mention of Satan links to the Epistle (and I believe it’s the only time “Satan” is mentioned in a Proper chant). The antiphon ends on an utterly grim note, without the least bit of consolation. No “happy ending”—not yet! A perfect anti-optimistic medicine to sober us up from our hedonistic Hollywood mentality.

SECRET. Mercifully receive, O Lord, these offerings, by which Thou art pleased to be appeased and, in Thy powerful goodness, to restore our salvation. Through our Lord...

Two quick points: the prayer tells us that God must be appeased (i.e., His wrath placated), and that we are in need of a salvation that comes only by God’s power. A perfect message against the miasma of Pelagianism and the Teddy-Bear God who has “always already” saved everyone.

COMMUNION. My soul is in Thy salvation, and in Thy word have I hoped: when wilt Thou execute judgment on them that persecute me? The wicked have persecuted me: help me, O Lord my God. (Ps 118:81, 84, 86)

Again, unlike Paul VI who removed hundreds of psalm verses to make the psalms safe for modern man, here the antiphon combines a lofty supernatural perspective with a plea for God’s vengenace on the wicked. A perfect shredding of the naive view that everyone is “just doing the best he can” and we’re all brothers—no enemies, no need for holy wars, inquisitions, the death penalty, etc.

See what I mean? This lex orandi for the 21st Sunday after Pentecost — all of it (except for the Secret) meant to be chanted — is uncompromising in its adherence to the full message of divine revelation, which frequently collides with the attitudes taken for granted by the modern West. And this is why the progressives in the Church hate the old rite so much and seek its elimination from the face of the earth. They do not believe the traditional Catholic religion and they cannot abide its unlikely survival.

So, next time you hear someone say: “Traditionis Custodes was caused by the bad attitudes of the trads; if they were content to quietly prefer the old rite, no one would have any problem,” be prepared to tell them, politely, to stuff it. The campaign against the old rite is a campaign against the faith it embodies and the faithful communities it sustains. Period.

Let the little children chant to Me

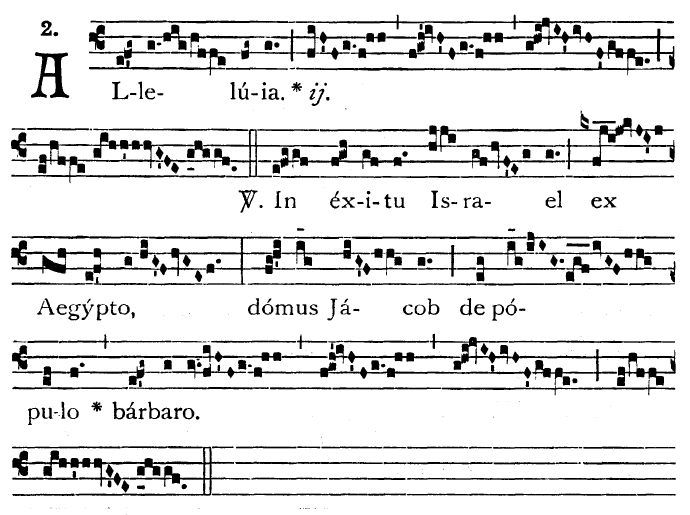

Lastly, one of the most absurd excuses is “we can’t sing chant, it’s too hard.”

I’ll admit that it requires work, but what worthwhile thing doesn’t? Nevertheless, even little children can be taught to chant beautifully. In fact, they pick it up rather well, as I’ve seen firsthand in my decades of musical experience.

Here is an initiative in Australia in which some traditionalist friends of mine are involved. (Let’s call it a bridge-building exercise.) It’s not everyday that you get to hear 1,100 children singing Gregorian chant together. Honestly, we should be seeing this kind of thing in every diocese of the world.

Here’s a picture of a schola of young women from a pontifical Mass a few years ago (I was also present in the choir loft as part of the mixed choir). The ladies are chanting the Gregorian propers of the Mass. Their average age is maybe 17.

This is what Pope Francis wants to kill, forever.

(Don’t start into the business “you could just do this at the Novus Ordo...” I was a music director in the new rite for 20+ years and I can tell you, the limits of what can be done musically at the Novus Ordo, even in the best of circumstances, are enough to drain every drop of enthusiasm for serving the Church out of the veins of most musicians. The traditional Mass was made for this music — indeed, was built in part by this music — and that is and will always be its natural home. Good sacred music rises and falls with the fortunes of the traditional Roman Rite. That is how things are; how they have been; and how they ever shall be, world without end.)

And then there is polyphony…

All this praise of Gregorian chant should lead no one to believe, for a moment, that I am in any way opposed to polyphonic music. On the contrary, I agree with the late great Dr. William Mahrt that “polyphony makes the chant sound so pure, and chant makes the polyphony sound so rich.” They fit each other hand-in-glove.

As Patrick Brill explains in his book The Great Sacred Music Reform of Pope St. Pius X, chant will always have chief place for the simple reason that there are parts of the Mass that can only be sung in chant, such as the readings, the dialogues, the preface, and the Lord’s Prayer. Beyond that, I would never want a Mass in which all the Ordinary and Propers were sung in polyphony. This is too much of a good thing. A judicious blend of chant and polyphony is best, where the choral forces are available. And Pius X’s reminder is timely for all of us, all the time: a Mass that is exclusively chanted lacks nothing in fittingness or wholeness. Polyphony is a welcome adornment, but it is not essential the way chant is.

I sing in a schola that sometimes joins with women for polyphony on special occasions. On one occasion we were rehearsing Palestrina’s Missa Aeterna Christi Munera for an upcoming feast. No matter how often I sing this Mass, I am always blown away by the transcendent beauty of it.

God gives special gifts to the Church in each age. The gift of sublime polyphony was given (primarily) in the Renaissance. For liturgical music, after Gregorian chant, there is nothing that can equal Palestrina, Victoria, Guerrero, Morales, Byrd, Tallis, and their contemporaries. Every Catholic in every place should have the opportunity to be lifted up by sacred music like this—by chant and, at least on special occasions, by the angelic strains of polyphony. It is nothing less than a crime to withhold this beauty from the People of God.

As Roseanne Sullivan eloquently says:

It is far from true that beautiful, richly decorated churches take away from the poor. On the contrary, they offer everyone a refreshing oasis in the aesthetic desert of the rest of our lives. The restoration of beauty to our churches and our liturgies, the beauty of profound music either directly from or at least harmonious with the Church’s sacred treasury of chant and polyphony, the beauty of solemn ritual, decor, reverence, and a sense of mystery—on top of clear catechesis—all could go a long way towards restoring people’s faith in the sacramental reality of the Word of God made flesh.

And while we’re sharing videos, here’s a 12-minute interview in which I talk about how I got into performing and composing church music, why we should love Gregorian chant and polyphony and why they’re perfect for the sacred liturgy, and what’s wrong with modern styles substituted for them:

Recommended resources on chant

Free scores and videos

Church Music Association of America (massive free resources in chant and polyphony!)

Sacred Music (chant provided by Institute of Christ the King)

The Parish Book of Chant (with a recording of every piece!)

Neumz (vast library of chant recordings)

Educational

Introduction to Working with Solfege (courtesy of FSSP)

Sung Mass Guide (courtesy of FSSP)

Peter Kwasniewski, Good Music, Sacred Music, and Silence: Three Gifts of God for Liturgy and for Life

Peter Kwasniewski, “On Singing Gregorian Chant Artfully” (Part 1, Part 2)

Robin Phillips, “The Power of the Pause”

Andrew Tolkmith, “Sea Shanties, Gregorian Chant, and Liturgical Work”

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you!

Thank you, Dr K. A great post with great resources, most of which I’ve used quite a lot and then new ones. I had never heard of the Seikilos epitaph. How wonderful that is!