In Praise of Spiritual Wedlock: St. Thomas on Christian Marriage (Conclusion)

Beatific spousal union needs an earthly analogue — and partly negates it

In the first two parts of this series, I spoke about St. Thomas Aquinas’s healthy and realistic appreciation of the goods of marriage. He sees procreation or offspring as the primary end in terms of the nature of the relationship between man and woman as such, but he sees sacramentality as the highest end of marriage between Christians, for it conforms them by grace to become living icons of the perfect, indissoluble union between Christ and the Church.

Meanwhile, since I started my series, the ever-admirable Robert Keim has been offering rich and nitty-gritty insights into the medieval conception of marriage at his Substack Via Mediaevalis.1 The question Robert and I are wrestling with can, in some ways, be epitomized in these two statements of Aquinas’s: “As regards what is signified [by the sacrament]…marriage is the noblest” of all; “as having something spiritual in terms of sign and effect, in that way it is a sacrament — and because it has the least of spirituality (minimum habet de spiritualitate), therefore it is put last among the sacraments.”2 How is it both the noblest and the least of the sacraments?

We will see that, for St. Thomas, these words of the Lord could well apply to marriage: “the last shall be first, and the first shall be last.” Aquinas had a balanced view that combines a healthy approval of everything God deems “good” (cf. Gn 1:31; 2:18) with a robust preference for that which God deems “better” (cf. Mt 19:10–12; 1 Cor 7:38), or, in Keim’s words, gold is better than silver, but silver is already beautiful and worthy; indeed we make chalices to hold the Blood of God in both gold and silver.

Imperfection of all sacraments

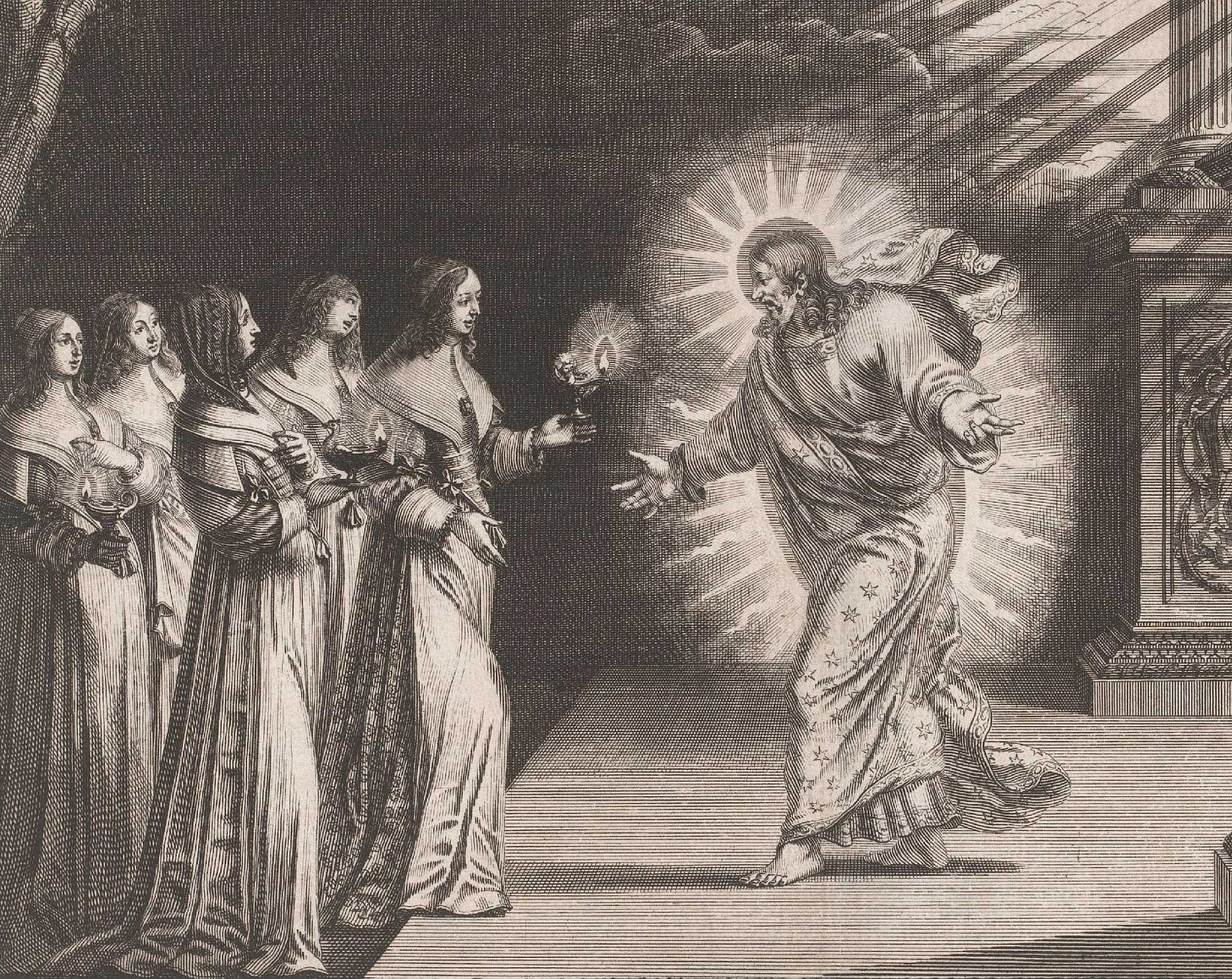

It is at the pinnacle of Thomas’s appreciation of marriage (which we have shown in part 1 and part 2) that we begin to understand his relativization of the sacrament of marriage. First and most basically, we have to remember that a certain imperfection attaches to all the sacraments, precisely because they are veiled and transitional. Recall the closing stanza of the Adoro Te (in the wording that is more likely Thomas’s own):

Ihesu, quem uelatum nunc aspicio,

quando fiet illud quod tam sicio?

Vt te reuelata cernens facie,

uisu sim beatus tue glorie.Jesus, whom veiled I now behold,

When will it come to pass — what I so thirst for?

That, looking intently upon your then-revealed face,

I may be blessed with the sight of your glory.3

The sacraments begin in us a work that is complete only in the life to come, when they shall have fallen away as means no longer necessary, however urgently needed they are in this present life. As Thomas states: “Conjoining to the [ultimate] end . . . according to the full participation thereof . . . is not accomplished by any sacrament, but the sacraments dispose [their recipient] to it.”4 Or as he puts it in the Summa:

The state of the New Law is between the state of the Old Law, whose figures are fulfilled in the New, and the state of glory, in which all truth will be openly and perfectly revealed — wherefore then there will be no sacraments. But now, so long as we know “through a glass darkly” (1 Cor. 13:12), we need sensible signs in order to reach spiritual things; and this is the province of the sacraments. (ST III.61.4, ad 1)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.