In the Footsteps of St. Paul (Part 3: Conclusion)

The House of the Virgin Mary, Ancient Ephesus, Turkish Rugs, Cave of the Apocalypse, the Palace of Knossos, & more

In the second part of this travelogue, published earlier this week, we visited Thessaloniki, looked at ancient music notation, reveled in the mystery of baptism through vivid icons, toured the ruins of Philippi, and visited a monastery on Mykonos.

Just a reminder: If you are receiving this post by email, clicking on the article’s title will bring you to my Substack page, where you can then click on any photo to enlarge it.

Day 9: Ephesus, Patmos

House of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Early this morning, we made a prayerful visit to the home of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Ephesus. I had been looking forward to this all the trip, and the experience did not disappoint!

As I mentioned in the first installment, it was my reading of Fr. Bernard Deutsch’s comprehensive work Our Lady of Ephesus, first published in 1965 and reprinted by Angelico Press, that convinced me that this house is indeed where the Mother of God lived for the final years of her life.

After St. John’s exile on Patmos ended, he returned to Ephesus to serve as its bishop. In accord with the words of Jesus on the Cross, Mary is John’s mother, and John is her son: one cannot imagine them living separated by a thousand miles (the distance between Jerusalem and Ephesus).1 Indeed, a basilica was built in ancient times over the tomb of St. John who died in Ephesus, and another basilica in the city was built under the express title of Mary — the first such church anywhere in the world, and the eventual location of the Council of Ephesus in 431. It is surely telling that the first church to be dedicated to Mary was located here, and that the place was chosen for the ecumenical council that would proclaim her Theotokos, the God-bearer.

There was a transcendent peace and humility about the place, a spirit of simplicity and purity (reminding me of Kierkegaard’s saying, “purity of heart is to will one thing”). Set in the midst of hidden woods, with a stunning view of the valley, it is easy to imagine Our Lady rapt in quiet contemplation and intercession for the Church, as she awaited her ultimate conformity to Jesus Christ by her own death and glorification.

I’m sure part of the reason for the special “feeling” of the place was the strict prohibition of photography inside the house. Everyone passing through simply had to be there. What was it like inside? A simple large room, with smaller niches at the far end, one of which was a prayer corner, and another the place where Our Lady slept. Archaeological evidence shows that there was originally a hearth in the middle of the building for cooking and warmth.

The photos here show the outside of the structure, rebuilt in 1951 on the original foundations and using original materials; a much earlier chapel had stood here, since early Christians too venerated this building, as Fr. Deutsch documents.

A practical reason this spot was chosen for a house is the natural spring next to it, which is still flowing to this day. Several pipes channel the water to faucets for pilgrims who either take some water in bottles or splash it on their hands and face (as I did). A “wishing wall” collects thousands of pieces of paper of Christians and Muslims begging help from God or from the Virgin Mary. This is admittedly a pagan custom, so I’m not quite sure why it’s allowed.

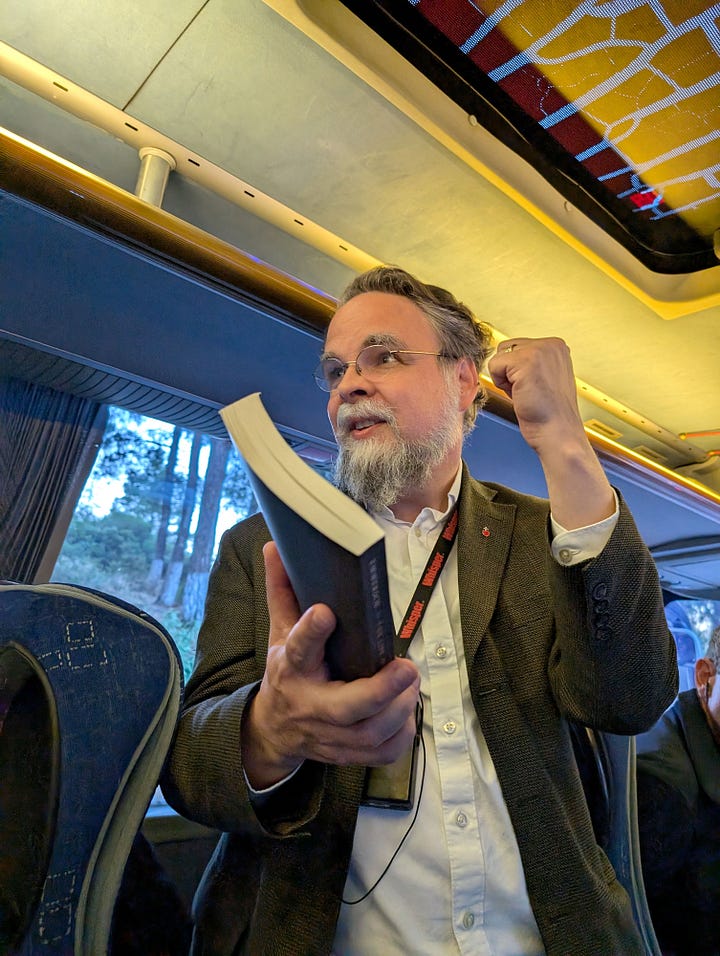

In the last photo in the gallery above, you can see me enthusing on the bus about Bl. Anne Catherine Emmerich’s The Life of the Virgin Mary, in the Angelico edition (and only that one). After all, it was her detailed visions of the terrain, locale, and architecture that led, not one, but two separate teams of European explorers in the 19th century to find this home of the Blessed Virgin after it had long been forgotten except by locals.

Ancient Ephesus

Of all the ruins we saw, those of ancient Ephesus were by far the most impressive, the most extensive and best-preserved. From what I recall of our Turkish guide’s explanation, Ephesus was abandoned at a certain point as no longer economically viable since its source of wealth was trade and the ocean kept stubbornly receding. There may have been a major earthquake in the picture too (it seemed like every place we visited had been felled by an earthquake, or several earthquakes). As a result, the ancient city was abandoned and its materials were never ransacked to build something else nearby. When modern archaeologists got around to digging out Ephesus, they found the boulevards, buildings, temples, mosaics, all very much intact. It was a wonder to behold — and of course, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world was here: the Temple of Artemis.

Of course, when you look at what’s left, you keenly feel the vanity of human empires. Someday the USA will look like this to a future civilization that digs it up. (If the world lasts that long.)

Our last stop in the half-day we spent in Turkey was at a place dedicated to making and selling handmade Turkish rugs. The demonstration of the technique was mind-boggling, and the rugs themselves were extraordinary. Here’s a brief video montage put together by Jeff, one of my fellow pilgrims:

And some photos:

Patmos

In the afternoon we landed at the isle of Patmos — if I may be allowed to say so, a beautiful spot for an exile, though I imagine it was quite a bit more rough and rustic in St. John’s day.

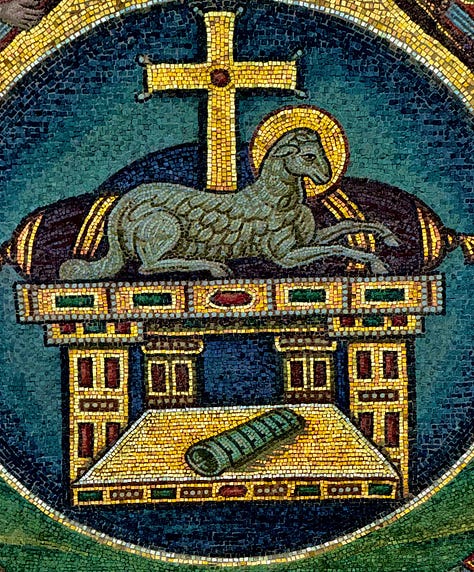

The first place we visited was the Cave of the Apocalypse, where St. John received the visions recorded in the final book of the Bible. Today it is an Orthodox chapel, connected with the island’s greatest monastery. One waits a long time to get in, as the space is very small. Over the top of the outside door is a mosaic of the central scene of the Apocalypse. Inside, one slowly walks along a passage that eventually goes past candles into the first cave, which is a chapel unto itself; then, turning to the right, and bowing under a low rock ceiling, one enters the cave itself, where John sought refuge for prayer during his exile on Patmos, and where he received the visions that are recorded in Revelation. The little fenced-off area in the corner is where John would sit, resting his head against the rock in meditation.

After visiting the cave, we went a bit further into the island to visit the Holy Monastery of St. John the Theologian. What a place! The frescoes and the icons are gorgeous past all imagining. I did not realize that the Greek Orthodox celebrate a kind of “assumption of John” parallel to that of the Virgin (see the fourth picture):

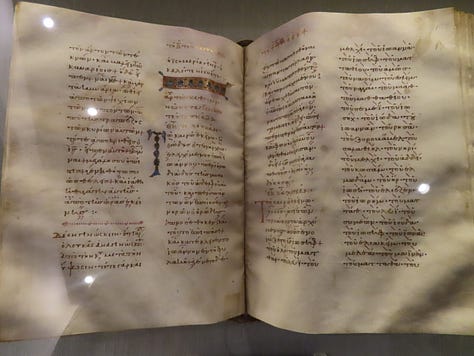

One of the highlights of the trip for me was the museum attached to this monastery. We had less than an hour in it, and I could have easily stayed all day long.

A few of many manuscript highlights: TOP ROW: Book of Job manuscript, 9th cent.; Gregory of Nazianzen, 10th cent.; Gospel Lectionary, 12th cent.; MIDDLE ROW: The Four Gospels, 14th cent.; Codex Purpureus, fragment of the Gospel of Mark, late 5th/early 6th cent.; Patriarchal and synodical sigillion of Sophronios of Constantinople, 1780; BOTTOM ROW: Privilege of Charles VI, emperor, in favor of the monastery, 1727; Chrysobull of Alexios I Komnenos, granting the entire isle of Patmos to St Christodoulos, founder of the monastery, in 1088.

Some additional items from the museum (I will limit myself!):

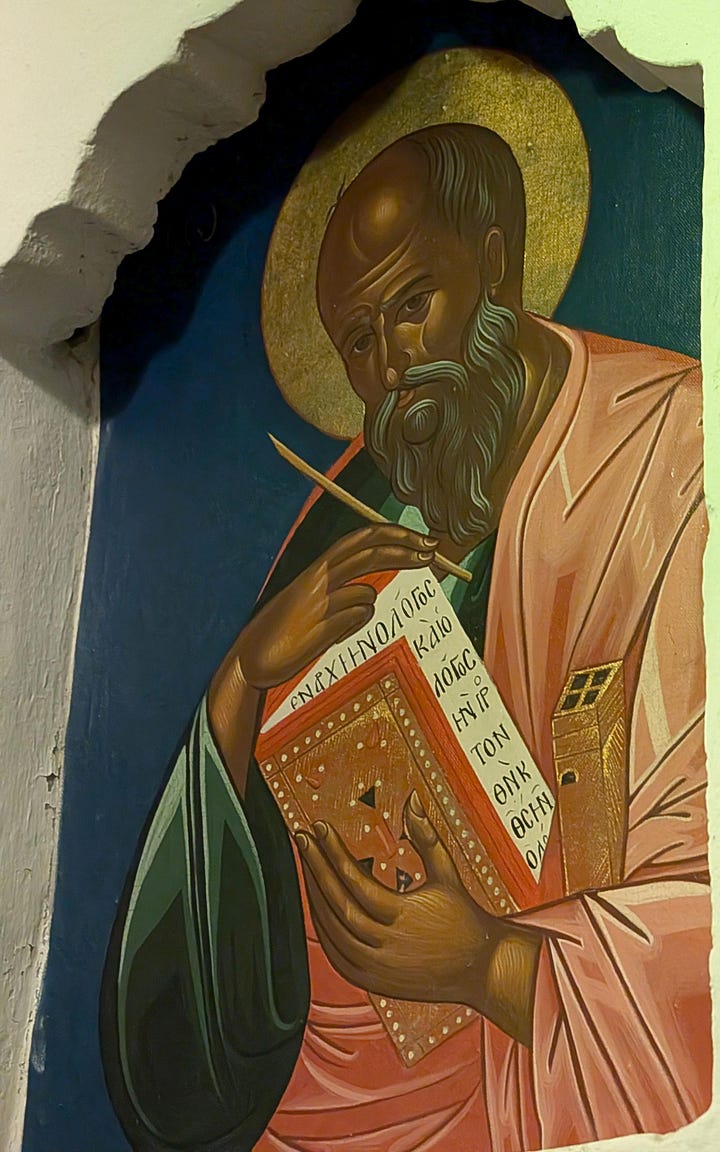

TOP ROW: handheld censer, 18th cent.; St. John dictating to his amanuensis; the miracles of St. Nicholas; MIDDLE ROW: a reliquary; a “monumental holy cup” for the Eucharist, 16th cent. Venetian; epigonation with descent of Christ into Hades; BOTTOM ROW: St. George, mid-14th cent. Cyprus; pectoral cross, 16th cent.; altar doors, Annunciation, St. Peter, and St. John, 15th cent.

That night, I was dreaming of Byzantine liturgical splendor. To me, it fits right alongside Latin liturgical splendor, but we see a lot less of that nowadays.

Day 10: Heraklion, Santorini

Heraklion

Crete has more of a magical aura in my mind than most places in Greece for the simple reason that I absolutely loved two World War II books written about British escapades there — books I would absolutely recommend for anyone who loves page-turning adventures of derring-do: W. Stanley Moss’s Ill Met by Moonlight and Xan Fielding’s Hide and Seek: The Story of a Wartime Agent. We only had a few hours here, so it wasn’t as if I could “explore Crete” (!), but at least I had a taste of it.

When the Muslims invaded Crete, they converted Heraklion’s Church of St. Mark into a mosque. When the Cretans kicked out the Muslims some time later, they returned the compliment by converting a newly-built mosque into a church. Today, this mosque-turned-church is dedicated to St. Titus, recipient of the eponymous epistle of St. Paul, and first bishop of the island of Crete. Titus’s skull has survived due to Venetian protection. When the Muslims invaded, the Venetians took the relic back to Venice. In 1966, the relic was given back to Crete. Today it is venerated in a side chapel, in a reliquary shaped like a Greek bishop’s mitre and housed in an elaborately carved casing.

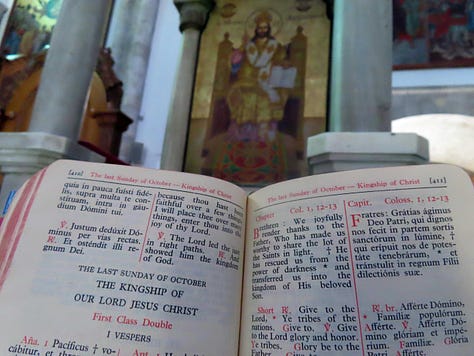

The Church of St. Titus was a perfect place to pray Lauds for the Feast of Christ the King, which traditional Catholics celebrate on the last Sunday of October. May the Lord grant us a new Christendom in which countless mosques will be leveled to dust or converted into churches as successfully as this one was.

We took a bus to Knossos and spent a good while among the ruins of the “Bronze Age archaeological site… a major centre of the Minoan civilization… known for its association with the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur.” There was something surreal about walking around buildings that dated from 1900-1350 BC — a site so ancient that the concept of an ampitheatre did not yet exist, as can be seen in the first photo, of an area where dramas were performed.

Santorini

As before with Mykonos, we arrived late afternoon, and by the time we got to the city, the sun had set, so we did not enjoy the stunning views of white buildings with blue domes that you see in the brochures (though we could see the gleaming white buildings as we approached the island, almost looking like snow-covered mountains from a distance). In compensation, as it were, the sun gave us a spectacular performance in its descent.

Day 11: Athens

Back from our cruise, we had a final half-day to walk around the city. It was at this point that my camera battery finally died, and I had forgotten to bring the recharger (but not a bad run, eh?). So the rest of the pictures here on out are from my fellow pilgrims.

The informal group in which I happened to find myself made a first stop at the Metropolitan (Orthodox) Cathedral of the Annunciation, the mother cathedral of all of Greece, built from 1842-1862. Its neoclassical architecture and Slavic-styled iconography make it quite distinctive:

Right next to this cathedral is a tiny medieval church, Panagia Gorgoepikoos (Γοργοεπήκοο, “She who is quick to hear”). The stonework was extraordinary, with knot patterns that reminded me, for all the world, of Celtic art. See what you think:

Since various groups of pilgrims had split up and gone off in different directions, we each saw something special that the other groups didn’t see. My fellow cantor Jonathan Arrington, whom I’ve mentioned before, overcame many obstacles to get to the rather remote location of the cathedral of the Greek Catholics in Athens. I am very pleased to say, based on the photos shared with me afterwards, that the Greek Catholics here are just as capable of building and decorating a magnificent icon-studded church as their Orthodox counterparts:

On the one hand, this makes me rejoice for our Eastern Catholic brethren; on the other hand, it makes me wonder again, with a groan: “What in the world went wrong with the West, that we took the perilous exit to Renaissance naturalism and ended up centuries later with incoherent jumbles of sappy sentimentalism or lifeless, barren barns of modernism? Well, that’s a question Hilary White’s been working on a long time, so I won’t go into it further here.

I am grateful that there seems to be a worldwide movement to restore authentic sacred art and architecture to the West. It parallels and sometimes intersects with the traditionalist movement. At the end of the day, what we need to see is a clear fusion of three elements: hierarchy, tradition, and art. That is a pithy way to describe the Counter-Reformation. No one who has even minimal consciousness can deny that we need a second Counter-Reformation to put the stake, once for all, through the heart of Modernism.

The Greeks, whose own postwar architecture is pretty bad (this cannot be denied, embarrassing as it is for a country sprinkled with some of the noblest monuments ever conceived by human genius), instinctively recognize that you cannot just tear down what is ancient to make way for what is modern. Look at this huge modern hotel that was built around a tiny historic chapel:

Another group that last day caught sight of this beauty of a church:

In the late afternoon we all met for a final sung Mass on the feast of the Holy Apostles Simon & Jude, which we were fortunate to hold at a Filipino chapel in Athens, whose sacristan opened up for us on the spur of the moment:

Before dinner that night, Fr. Pablo blessed all the icons and other holy objects the pilgrims had obtained along the way, using, of course, the Rituale Romanum’s appropriate blessings, and sprinkling the whole lot with Epiphany water that I had brought along. (I always travel with a bottle because I don’t feel comfortable sleeping in any hotel room that hasn’t been thoroughly doused with it, followed by a St. Michael Prayer.)

Incidentally, I found three lovely icons that filled in gaps in my icon corner at home: one of St. Andrew looking worried and sleep-deprived, one of St. Paul looking ready to box with any antagonist, and one of St. John with a forehead giant enough to serve as an altar card for the Last Gospel.

Visiting the ancient and sacred sites, and being surrounded by icons, has a way of relativizing the nonsense going on in the Church, and making one live closer to the fundamental realities that endure.

The Lesson of the Liturgy

On our trip, three of our tour guides were devout Greek Orthodox Christians. Each one of them said words to this effect: “Orthodox worship is full of mystery, holy images, symbolism, and chanting; it’s ancient and elaborate.”

It had never occurred to them even once that Roman Catholic worship could be described in the same terms. Our traditional worship, which emerges out of the first millennium of the undivided Church, retains nearly all the same features to this very day (including an iconostasis, which for us takes the sonic form of Latin, Gregorian chant, and silence, together with the communion rail), yet the new liturgy that replaced it adopts the Protestant emphasis on readings, preaching, vernacular singing, Last Supper banquet, and suchlike.

These Orthodox tour guides had only ever been in contact with Novus Ordo groups and had never encountered a TLM group until ours. No wonder they thought they had a monopoly on all those qualities. The guides who got to know us better quickly learned that Catholic worship has a more ancient and more orthodox face—and they seemed grateful to discover this fact.

These experiences have convinced me more than ever that nothing could have been more foolish for the West than to turn its ecumenical attention toward convergence with Protestants rather than toward reunification with the East. We should have leaned heavily into what most unites the apostolic churches, rather than discarding it to emulate mistakes of the Reformation era.

A traditional liturgy valued by a long line of saints and handed down by uninterrupted piety is the natural counterpart of Sacred Scripture, the Church Fathers, sacred art, dogmatic theology, and the pursuit of holiness. Where the latter are taken seriously, so will the former be; and vice versa. When rupture occurs in one area, ruptures will begin in the other areas too.

To close this three-part travelogue, here’s a splendid 3-minute retrospective video compiled by our chaplain, Fr. Pablo, from footage he took along the way. The singing is either from the Greeks we heard, or from our own group.

Thank you for reading, may God bless you, and may “our most holy, pure, blessed, and glorious Lady, the Theotokos and ever-virgin Mary,” intercede for you and yours this Advent.

Fr. Deutsch patiently explains why the tradition that Our Lady died in Jerusalem is to be rejected. There are many arguments against it, as well as many in favor of Ephesus as the location of the Dormition/Assumption.

"These experiences have convinced me more than ever that nothing could have been more foolish for the West than to turn its ecumenical attention toward convergence with Protestants rather than toward reunification with the East. We should have leaned heavily into what most unites the apostolic churches, rather than discarding it to emulate mistakes of the Reformation era." Yes. I allow myself to indulge in an alternate timeline, in which V2 never happened (or at least the NO never implemented), Russia was properly consecrated to Our Lady's Immaculate Heart, and Pope Leo XIV presided at the reunion celebration in Hagia Sophia for the 1700 year anniversary of Nicaea.

Beautiful churches! Wow! I love this quote—

“These experiences have convinced me more than ever that nothing could have been more foolish for the West than to turn its ecumenical attention toward convergence with Protestants rather than toward reunification with the East. We should have leaned heavily into what most unites the apostolic churches, rather than discarding it to emulate mistakes of the Reformation era."

I don’t think I ever even thought of this as an option growing up, but I think it is spot on. I think it’s hard for a lot of Americans to conceive of putting ecumenical efforts towards this because there are so few Orthodox in America so the Orthodox seem very foreign to us.