Living to Die, and Dying to Live

The Christian revolution turns our conceptions of life and death upside-down, overcoming the despair of fallen (and modern) man

Requiescat in pace

Last week, on April 28th, Fr. Terrence Gordon, FSSP, died from a heart attack (although not before his brother, also a Fraternity priest and stationed at the same parish, was able to give him the last rites). May his soul, and the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace. Amen.

Among the many hit hard by Fr. Gordon’s death is a friend of mine, the mother of a large family, who spontaneously told me that she had been receiving long-distance spiritual direction from him every week for seven years and that it had helped her in her spiritual life more than she could possibly put into words. I have a feeling there are many stories like that yet to emerge, and many known to God alone.

Fr. Terrence (as I will call him to avoid confusion with his two blood-brother-priests) was not a close friend of mine, but I did have the rare opportunity to spend an intense week with him in the wilderness of Wyoming on a grueling backpacking trip in 2012 (the trip lasted longer but Father peeled off of our faculty-staff group to join a student group as its chaplain). A former Marine, Fr. Terrence carried a heavy pack with his clothing and fair share of food as well as the most complete portable Mass kit I’ve ever seen, and never complained once. He always had a smile on his face and a kind word to speak. His offering of Mass in the remote wilds, with giant boulders serving as his altar, was serene and focused. (On my Facebook page I shared some other photos taken by various friends on that trip, which we’ll certainly never forget.)

Memento mori

Fr. Terrence was only 52 years old when he died. I, too, am 52 years old, and so the news of his death—in addition to being a cause of sadness, an occasion of grateful remembrance, and a call for prayer—was a memento mori. No one knows the day or the hour. At any moment the Lord may call us to Himself, to His judgment seat, to His throne, and ask for an accounting of the life He has given us: what we have done with His gifts and graces, how we have loved Him and all those who bear His image, especially the ones He has entrusted to us.

Memento mori. Christians used to ponder death frequently. It was a common theme of meditations, even daily. Skulls and bones, either figurative or literal, were used to decorate crypts and chapels. Relics were placed at every altar, often full skeletons in a case underneath the mensa (seeing this in the churches of Europe is often a great surprise to American tourists, who could hardly imagine doing something like that). Great painters often portrayed St. Mary Magdalene, St. Jerome, St. Francis, and many others as penitent cave-dwellers with a skull among their few possessions.

Moderns run away from death

In almost every phase of history prior to our own, death was a common occurrence and everyone saw it in their homes. Those declining in health were not housed elsewhere, to be cared for by a special class of workers; the dying were not removed and hidden from the rest of humanity. Life and death rubbed shoulders under the same roof. Truth be told, most people would still prefer to die this way—at home, surrounded by loved ones, and, for Catholics, with a priest at the bedside to prepare us to meet the Lord.

Even if our contemporaries have reached a nihilistic nadir in attitudes and practices, the flight from the Last Things is not a phenomenon of recent vintage. Early modernity was already impatient with the Christian stance of resignation to suffering and death. The “father of modern philosophy,” René Descartes, stated that his approach to philosophy aims at the prolongation of natural life. He tells us in a famous passage in the Discourse on Method: “In place of that speculative philosophy [i.e., metaphysics] taught in the schools, it is possible to find a practical philosophy,” by means of which we could

render ourselves as masters and possessors of nature. This is desirable not only for the invention of an infinity of devices that would enable one to enjoy trouble-free the fruits of the earth and all the goods found therein, but also principally for the maintenance of health, which unquestionably is the first good and the foundation of all the other goods of this life… If it is possible to find some means to render men generally more wise and more adroit than they have been up until now, I believe that one should look for it in medicine…. One could rid oneself of an infinity of maladies, as much of the body as of the mind, and even perhaps also the frailty of old age, if one had a sufficient knowledge of their causes and of all the remedies that nature has provided us.[1]

The forgotten God and the unintelligible creature

The purely naturalistic, horizontal, secular, this-worldly mentality that first arises in Cartesian philosophy developed over the centuries into “scientism,” that is, a positivist, materialist, reductionist vision of the whole of reality, including human beings. John Paul II well describes the shift:

When the sense of God is lost, the sense of man is also threatened and poisoned, as the Second Vatican Council concisely states: “Without the Creator the creature would disappear… But when God is forgotten the creature itself grows unintelligible.” Man is no longer able to see himself as “mysteriously different” from other earthly creatures; he regards himself merely as one more living being, as an organism which, at most, has reached a very high stage of perfection. Enclosed in the narrow horizon of his physical nature, he is somehow reduced to being “a thing,” and no longer grasps the “transcendent” character of his “existence as man.” He no longer considers life as a splendid gift of God, something “sacred” entrusted to his responsibility and thus also to his loving care and “veneration.” Life itself becomes a mere “thing,” which man claims as his exclusive property, completely subject to his control and manipulation.

Thus, in relation to life at birth or at death, man is no longer capable of posing the question of the truest meaning of his own existence, nor can he assimilate with genuine freedom these crucial moments of his own history. He is concerned only with “doing,” and, using all kinds of technology, he busies himself with programming, controlling, and dominating birth and death. Birth and death, instead of being primary experiences demanding to be “lived,” become things to be merely “possessed” or “rejected.”…

In such a context suffering, an inescapable burden of human existence but also a factor of possible personal growth, is “censored,” rejected as useless, indeed opposed as an evil, always and in every way to be avoided. When it cannot be avoided and the prospect of even some future well-being vanishes, then life appears to have lost all meaning and the temptation grows in man to claim the right to suppress it.[2]

How hopeless is the man without faith! Years ago, I attended a performance of Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. It struck me as a superb expression of the existentialist perplexity with, fear of, anxiety about, and despair over death—its inevitability, its leering emptiness, its pointlessness. The play put into intelligible language the vague and voiceless fears of man confronted with his own “ending,” which, for the unbeliever, is like stumbling blindly into a void.

The scientific dream’s failure

In spite of Descartes’s overconfidence four centuries ago, science has not been able to deliver the goods. We cannot abolish death, and we know it. We cannot give it a meaning ourselves. Face to face with death, modern man is thrust into a scorching silence. It makes him frantic (as we saw during the Black Death Covid). It exposes his utter helplessness, the vanity of his technology, the fragility of his power, the hollowness of his desires. Death without God displays what man in his nakedness is: a blustering coward, a boastful fraud.

Modern secularists (and, I’m afraid, too many Christians who are virtually secularists) stop at nothing to avoid death, postpone it, or medicate it into oblivion. They hide death from themselves and from each other, whisking away any appearance of it as quickly as possible and packaging it with Hallmark sentimentality and revisionist eulogies that, in a pseudo-Christian context, quickly turn into spontaneous local canonizations. At rare moments like this, the reality of an eternal state after death and the promise of immortal life are paid lip-service—we might call this the lingering “residue” of Christianity—but no one pays it much attention in day-to-day life, and increasingly it is forthrightly denied, especially by younger generations brought up with no religion at all.

Indeed, there is good reason to believe that the culture of death came into being and endures precisely because of a profound inability to reckon with mortality, which leads on the one hand to contempt for life (“What’s it worth, anyway?”) and on the other hand to idolatry of life (“I want to live as I please, as long as I please—let nobody interfere with my desires!”). Euthanasia and abortion are the practical consequences of not knowing how to reckon the worth and purpose of one’s own life and of human life as such.

The paradox is that unless one can explain what death is—where it came from, what it’s for—one cannot live a fully human life. To be alive means to face the future from out of the present. The ultimate earthly horizon is death. If one cannot face death, or, put differently, if there is nothing one loves so much that one is prepared to give up one’s life for it, one is doomed to imprisonment in a present moment that is incapable of yielding to and fertilizing the future.

Life and death in the Christian Faith

The Christian revolution changes two things: the meaning of life and the meaning of death. That means it changes, potentially, everything—for those who embrace it.

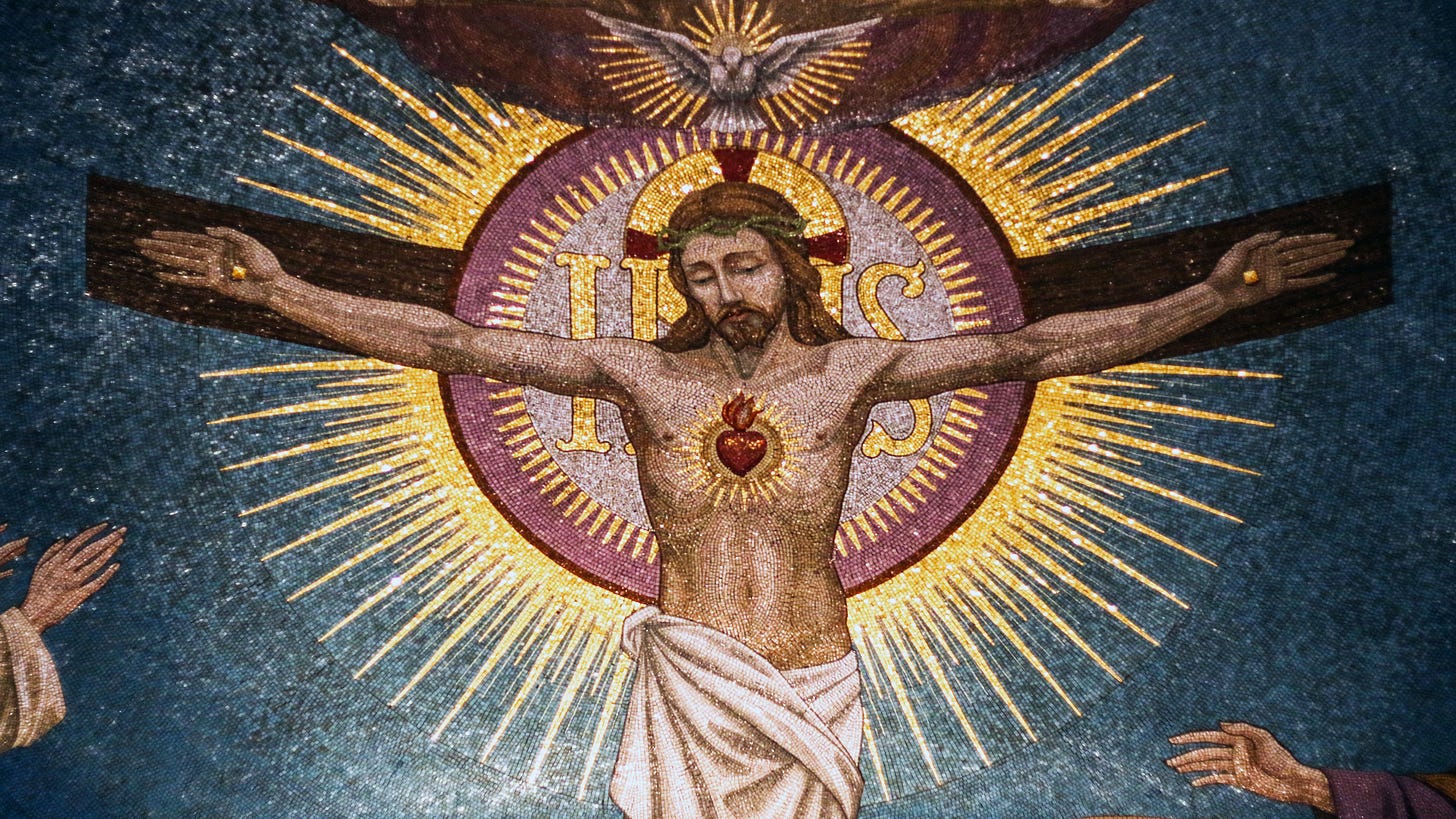

Socrates had famously said that philosophy is a preparation for death: this is true, but it remains tormentingly obscure and, in any case, overly intellectual. Christ teaches that life is a transitus, a passing over, to the Father. Death is the moment when this transitus is actualized. The Lord Jesus lived that transitus in an unmistakable way: every moment of His life was turned to the Father, and His life culminated in a death of love. He came into the world to give us an example of how to live and die, and, just as importantly, to give us the power to do so.

Perhaps the most striking part of the Gospel is that, unlike the great teachers of philosophy, Christ does not merely tell us what to do or show us how to do it, but gives Himself to us in order that we may do it with Him. In other words, the power to live and die comes from Christ. Union with Christ is the only way to live well and to die well. Since these are the only things that can possibly matter to human beings who have achieved any degree of self-awareness, Christ is the key to all that matters.

The mystery of predestination in Christ and conformity to His death is, in fact, the only answer to this stubborn perplexity concerning the whys and wherefores of birth and death, of coming-to-be and passing-away, the mutability and accidentality of the life of the individual man or woman, which “passes like a shadow,” as the Psalmist puts it (Ps 101:12; Ps 143:4). Without this answer, human life runs the risk of appearing utterly meaningless.

The revolutionary aspect of the Gospel can be seen negatively if we consider that apart from it, apart from that union with Christ, men live tormented by the prospect of death. As the Epistle to the Hebrews expresses it: “Because the children are partakers of flesh and blood, he also himself in like manner hath been partaker of the same: that, through death, he might destroy him who had the empire of death, that is to say, the devil: and might deliver them, who through the fear of death were all their lifetime subject to servitude” (Heb 2:14–15).

“Death, where is thy sting?”

At one point in the magnificent film Into Great Silence, we see an interview with an elderly and blind Carthusian monk, who says:

Why be afraid of death? It is the fate of all humans. The closer one brings oneself to God, the happier one is. The faster one hurries to meet him. One should have no fear of death. On the contrary! For us, it is a great joy to find a Father once again. In God there is no past. Solely the present prevails. And when God sees us, he always sees our entire life. And because he is an infinitely good being, he eternally seeks our wellbeing. Therefore, there is no cause for worry in any of the things which happen to us. I often thank God that he let me be blinded. I am sure he let this happen for the good of my soul. It is a pity that the world has lost all sense of God. They have no reason to live any more. When you abolish the thought of God, why should you go on living on this earth?

The central audacious claims of the Christian Faith are well expressed in the following words by Fr. Claudiu Merdariu:

Departing from the event of His death on the Cross—the peak of paradoxes (Life Itself is killed; by death He conquered death)—in which the lowest, most degrading, and darkest point in Christ’s life becomes the highest, the most glorious, and brightest point of God’s intervention in the history of humanity, we can arrive at the point of our divine filiation, which finds its supreme model in that of Christ. It is in serving others that we become free, and it is in our bond to the Father that we are delivered from the slavery of sin and receive the freedom of a son. It is through the pains of Calvary that we are born to eternal life and through the cry of Christ on the Cross that we see the light of eternal day. “It is in His own filial dying that Christ became the way of access to the Father, the sacrament of the divine birth. We are born as sons of God in one and the same place, on a single and the same date: in the Son, in the moment of His death in which we communicate” (Durwell).[3]

In the same spirit Fr. Michael Casey observes:

For the moment we are landlocked in space and time, but this separation [from God] will not be permanent. Like a thief in the night, the hour will come in which we are summoned forth to our eternal destiny. If we have learned well the message of the Gospel, we will live our lives with our eyes fixed on eternity, not allowing ourselves to be weighed down by concern for what is transient and ephemeral. The “ethics” promulgated by the New Testament are designed for this single purpose. They are not primarily a charter for the perfect society on earth, but a map that will guide us to heaven.[4]

A map is needed for a journey. The Christian conception of life is dynamic, moving toward ever-greater dynamism: for we are on pilgrimage to eternal joy. Speaking of the vocabulary for death in early Christian Latin literature, Albert Blaise writes: “Death was not [spoken of as] an end; it was a crossing-over (transitus), a departure (profectio), a change of home (migratio, commigratio), a recall to God (accitus, arcessitio, vocatio), or again a sleep (dormitio) awaiting the resurrection.”[5] Note the hopefulness, even tenderness, of these ways of speaking! Death is fearful to us as animals, for it is the end of our earthly state of existence; but the eyes of faith see it as the departure for another world, a change of domicile, a migration to the Fatherland, a response to God’s beckoning, a longed-for resting in Him.

A death of love

As Pope Benedict XVI said: “In Christ, we have the promise of definitive redemption and the certain hope of future blessings. Through Christ we know that we are not walking towards the abyss, the silence of nothingness or death, but are rather pilgrims on the way to a promised land, on the way to him who is our end and our beginning.”

The secret to finding meaning in death and to preparing well for it is Christ and He alone—union with Him in His Mystical Body. If we are His, then His life is ours, and His death can be ours as well. When I say “His death” I do not mean a death by crucifixion (although this will be the privilege of some of the martyrs, such as the brothers Peter and Andrew). I mean a death of love: a death that can say, about our enemies and persecutors (if we have any), whom we naturally ought to hate, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do”; and, essentially, a death that says to God, whom we might be tempted to distrust, “Father, into Thy hands I commend my spirit.”

Fr. Ceslaus Spicq writes: “Christian morality is a redamatio, a return of love to Christ’s love revealed on Calvary. Consequently, to love (agapan) and to die (apothnēiskein) are one and the same thing. Death, physical or moral, is a sort of sacrament of love; it is love’s sign and efficacious symbol.”[6]

In his 2006 meditations on the Way of the Cross, Cardinal Angelo Comastri made just this connection:

“For our sake he was crucified!” Jesus, at his death, embraced the tragic experience of death as it had been fashioned by our sins; yet, in his death, Jesus filled death itself with Love, he filled it with the presence of God. By Christ’s death, death itself was vanquished, for he filled death with the one power capable of canceling the sin that had spawned it: Jesus filled death with Love! Through faith and baptism, we have access to the death of Christ, to the mystery of the Love by which Christ himself tasted and conquered death…and this in turn becomes the first step of our journey back to God, a journey which will end at the moment of our own death, a death experienced in Christ and with Christ: in Love!

We die as we have lived

The great preacher Fr. Henri-Dominique Lacordaire expressed the Christian view powerfully when he said: “Death is the term and decisive moment of life. In the face of death, man appears truly great. And until that solemn, powerful, and fortunate day, he has not yet reached the heights of his greatness. All virtues need the consecration of death to appear in all their brilliance.”[7]

St. Jerome, too, writes: “In the lives of Christians, we look not to the beginnings but to the endings” (Letters, 54.6). Both are echoing the Bible: “A man’s end tells his story” [סוף אדם יגיד עליו] (Sirach 11:27) and “If the tree fall to the south, or to the north, in what place soever it shall fall, there shall it be” (Eccles 11:3). The non-canonical text of 4 Maccabees 7:15 says, concerning the martyr Eleazar: “O man of blessed age and of venerable grey hair and of law-abiding life, whom the faithful seal of death has perfected!” L.-H. Petitot soberly explains: “History…teaches us that we must analyze a man’s death in order to recognize and determine his character.”[8]

Why is so much resting on the end? For the simple reason that as a man lives, so will he die. If he lives by faith in the Son of God and in union with Him, and if this is his first priority, he will certainly die with faith in Christ and united to Him. We should remind ourselves of this truth when we are tempted to fear our death, tempted to anxiety about our eternal fate. Christ desires you and me to be with Him forever. That is why he lived and died for us. That is why He gives Himself to us most intimately, in the gift of divinizing grace and in the gift of the Eucharist. He is at work to save our souls and to bring us to the Father’s house.

Our frailty is no obstacle to God’s love

Dame Julian of Norwich, in her inimitable way, reminds us that God is not outmaneuvered by our failings:

I see that mercy is a sweet, gracious working in love, mingled with plenteous pity. Mercy works by preserving us and mercy works by turning all things to our good. In love, mercy allows us to fail somewhat, and in failing we fall, and in falling we die. For death is inevitable since we lack the sight and experience of God who is our life. Our failing is full of fear; our falling is marked by sin; our dying is sorrowful. Yet in all this the sweet eye of pity never departs from us, and the working of mercy never ceases.[9]

God’s mercy is great, and this is why there are deathbed conversions. There are some souls that God, by His inscrutable will, allows to “catch up” with themselves and with Him in the last moments of life and to turn their being toward Him, making of an otherwise botched life a widow’s mite for the treasury and putting their souls into God’s hands, starting the transitus as their last breath fails. Such a soul, too, has made of its life—the end of its life, at least—a transitus to the Father, and passes through the gates of death into eternal life, even if it may require much purgation to redeem the wasted gift of life, so as to live the hidden life of Christ and walk the way of His Cross that all the saved must walk.

Far better it is to live right now, and for one’s entire life, in love with God. Then, at the end, one can joyfully give one’s entire life back to Him, permeated with the scent and sound and look of Christ, and the Father will be well-pleased with His beloved. But how do we go about this living toward God? The answer can be summed up in one word.

Prayer is the best preparation for death

Prayer is giving ourselves actively to God; death is giving ourselves passively to God. That is why only the one who prays is prepared for death; that is how it can be for him a way of giving himself in love to the Lover of souls. God gave us breath to praise Him. The ultimate act of praise, then, is to give our last breath back to Him: it is all we have to give, and, in a way, it represents all we are.

Our fundamental “work” as Christians is to surrender—again and again—to God in the depths of our will and thereby with all our powers, to allow him to shape us by the circumstances of our lives as the potter shapes the clay; in short, to let ourselves be loved into the kingdom of heaven. Obviously this demands a struggle against sin as well as the practice of the virtues—but these are not the essence of salvation. Salvation is perfect communion with the eternal, living God.

Most of the time, what we have to fight against are not huge vices but the little vices that eat away like acid into the armor of our Christian life—indifference, laziness, preoccupation with fleeting affairs. We have to keep alive in ourselves the thirst for eternal life, the desire for beatitude. Every day we get on our knees to say: “Lord, I am yours, I want to be entirely yours. Take away all that keeps me from you. I am a sinner but I plead for your mercy. Remember me when you shall come into your kingdom. Jesus, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

“Take away all that keeps me from you” ultimately means “Take my mortal human life, so that I may be with you in heaven.” A sincere prayer for salvation is a prayer for death and eternal life. As Christians we have to come to grips with the fact that we were not placed in the garden of this world to live here forever, even if we could make it happen as Descartes wished. We were put here, rather, to till and keep the garden for as long as the master wishes—and when he summons us, saying “your assignment is done,” it is either to receive the reward of our labors for Him, or to be punished for refusing to serve Him. That is all. If we bear this destiny in mind, our life comes into focus, the proportions of things are seen correctly, and our actions—and especially our sufferings—shimmer and throb with meaning.

May the soul of Fr. Terrence Gordon, and the souls of all our beloved dead, rest in the peace of Christ, and may the Lord grant us the gift of final perseverance in His love.

Weekly Roundup

It wasn’t planned this way, but my May 1st article at New Liturgical Movement, “The Beautiful Death: Why We Favor Cut Flowers in the Sanctuary,” bears an odd correspondence to this Substack post.

My article at OnePeterFive, May 3: “Can a Case Still Be Made for Reforming the Reform?”

The lecture I gave in Mt Pleasant, South Carolina, on April 20, 2023, is up at my YouTube channel: “Why Should Pope Francis and the FBI Care about the Latin Mass?” (And Part 2, which contains the coda to the lecture, and the Q&A.)

[1] Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy, trans. Donald A. Cress, 4th ed. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998), 35.

[2] Encyclical Letter Evangelium Vitae, 22–23.

[3] From his unpublished licentiate thesis at the International Theological Institute in Gaming, Austria.

[4] Fully Human, Fully Divine: An Interactive Christology (Liguori, MI: Liguori Publications, 2004), 307.

[5] Paul Avray, Pierre Poulain, and Albert Blaise, Sacred Languages, trans. J. Tester, Twentieth Century Encyclopedia of Catholicism, vol. 116 (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960), 163.

[6] Agape in the New Testament (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2006 [1965]), 2:315. Fr. Spicq goes on to explain: “By nature an active and manifest love, agape finds its proper means of expression in Jesus’ example: to die to self as Christ died for God and his brothers…. ‘We are the Lord’s’ (tou kyriou esmen [Rom. 14:8])! The formula sums up the entire Pauline religion; we exist supernaturally only in and by Christ: ‘You are in Christ Jesus’ (1 Cor. 1:30). In him we become new creatures (2 Cor. 5:17), new men, true sons of God. The creation of the interior man presupposes the disappearance of the past, death to the world and to sin, and a ‘co-crucifixion with Christ’ (Gal. 2:19) which will allow us to rise with him and live his glorious life (Gal. 2:20). The believer is the possession of his Lord. He belongs to God body and soul. He lives from God and, consequently, for God. The common life which God and the believer share is agape itself.”

[7] L. H. Petitot, The Life and Spirit of Thomas Aquinas, trans. Cyprian Burke (Chicago: The Priory Press, 1966), 148.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Revelations of Divine Love, 14.

Thanks, Dr. K. A timely reminder and I think you are spot-on about the power of COVID--it revealed the manifest fear of death in our culture. My father and I were not always on good terms, but at the end of his life we grew closer; my presence at his death (at home under hospice care) was a tremendous gift for me and, I hope, for him.

"Mass in God's cathedral." I would love to hear more about what that experience was like.