For a very, very long time, it was fashionable for liturgists to look down their long noses at the Middle Ages, seeing it as a period of regrettable ignorance if not deplorable decadence. The medievals simply didn’t have “science,” you see, and they couldn’t help making a mess out of everything they touched. The Baroque was even worse, because, although the Enlightenment saw the first stirrings of “science,” an ossified attachment to tradition combined with quirky subjectivism produced Baroque liturgy, which is the bête noire of any self-respecting enthusiast for Christian antiquity (as selectively and imaginatively reconstructed by scholars, of course!).

These anti-medieval, anti-Baroque liturgists were the ones who drove the wrecking-ball machines of the 20th century and left behind a wilderness of rubble with a few modernist sculptures poking up here or there, which some people still feel obliged to honor.

I need not belabor the point.

The happy news is that this view of the benighted Middle Ages has been steadily losing ground for a long time. One major transition occurred when medieval art and architecture were rediscovered as marvelously creative and appealing to more sides of human nature than either academic naturalism or spasmodic modernism. Another major transition occurred when medieval philosophy and theology were rediscovered as vibrant sources of truth, more sophisticated and penetrating than anything the moderns had come up with (almost in inverse proportion to their boasted originality). A final transition occurred when the rich, intricate, profoundly meaningful tapestry of medieval life, culture, and liturgy became a regular topic of study, particularly by historians (Eamon Duffy comes to mind), who discovered that, as a matter of fact, the common people were quite sufficiently aware of and integrated into the mysteries of their religion.

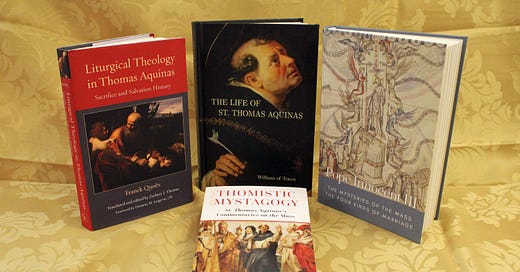

In today’s article, I will first discuss a major early thirteenth-century figure, Pope Innocent III, sharing — for the first time online — the Foreword that I contributed to a new translation of his work. Then I will joyfully run through the flowering fields of other recent books that show us the depth and beauty of medieval liturgy and the theological work based on it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.