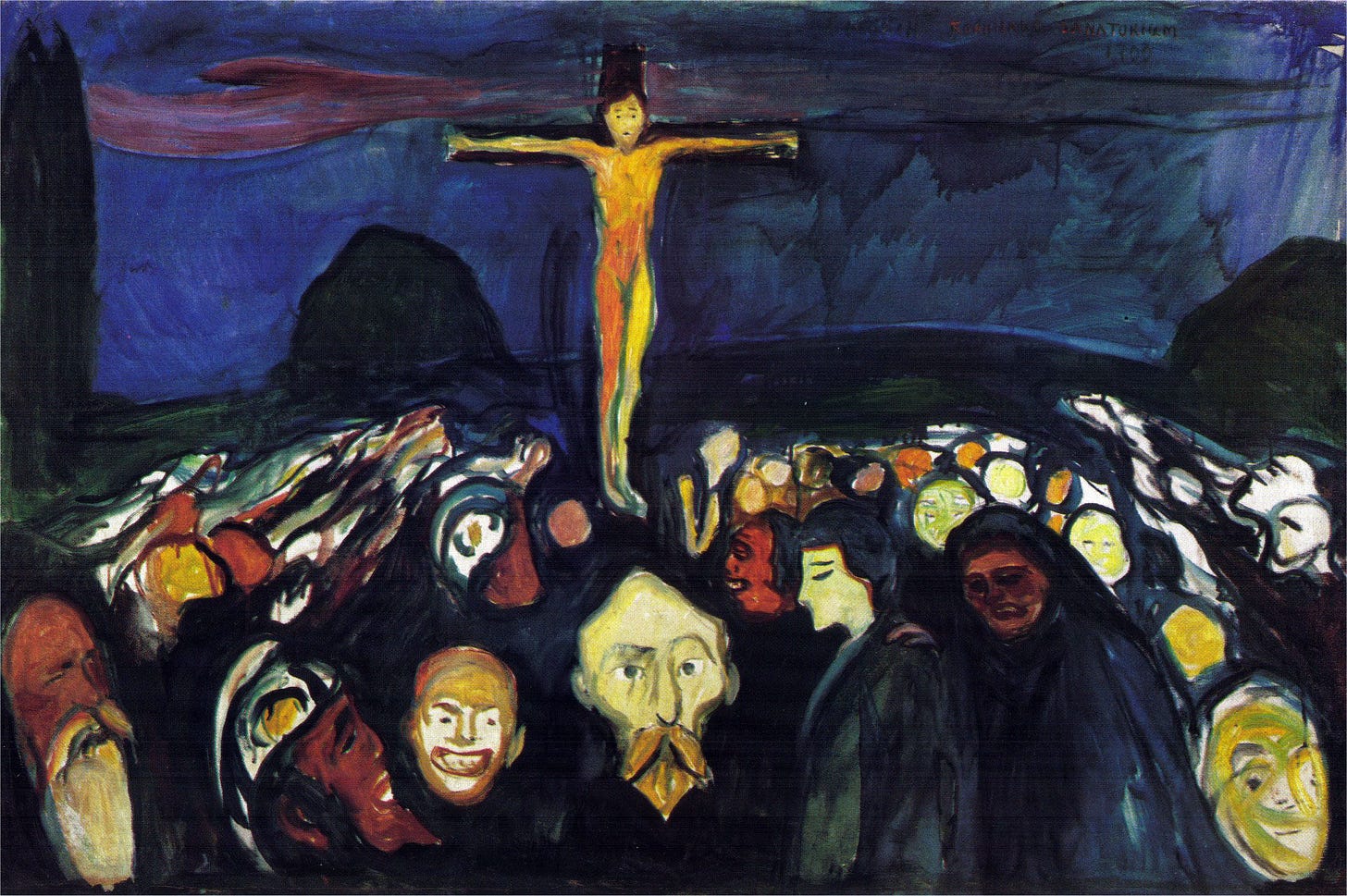

A few days ago, I spoke about the grace I received last Holy Week from listening to the chanting, over and over again, of Psalm 50, the Miserere, by the Benedictine nuns in Gower. Something that might have seemed “on paper” like “useless repetition” came alive for me as a source of life, an intensely focused beam of light that sought out the dark places to reveal them to the Lord and to surrender to His invasion of love.

And then I wondered more about what happens when you get rid of such things. When you chop them out, toss them aside, suppress, ignore, even ridicule. What spiritual effects will this have? I am increasingly convinced that at least one of the reasons the Lord has allowed the growing apostasy of the past sixty years is to show, unmistakably, to the eyes of any who care, the profoundly disintegrating effects of turning one’s back on tradition, as if to say: “You want to do without Me, and you want to do without the disciplines I have inspired to lead you to Me? Well, then, have at it, and you will see how much you can do on your own, with your banal on-the-spot fabrications.”

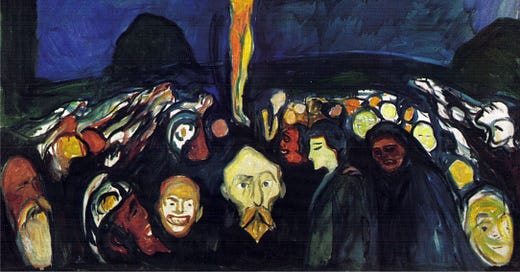

In one of the most brilliant short essays ever written about music, modestly entitled “Thoughts about Music,” Josef Pieper endorses “the disturbing observation equating the history of Western music with the history of a soul’s degeneration.”1

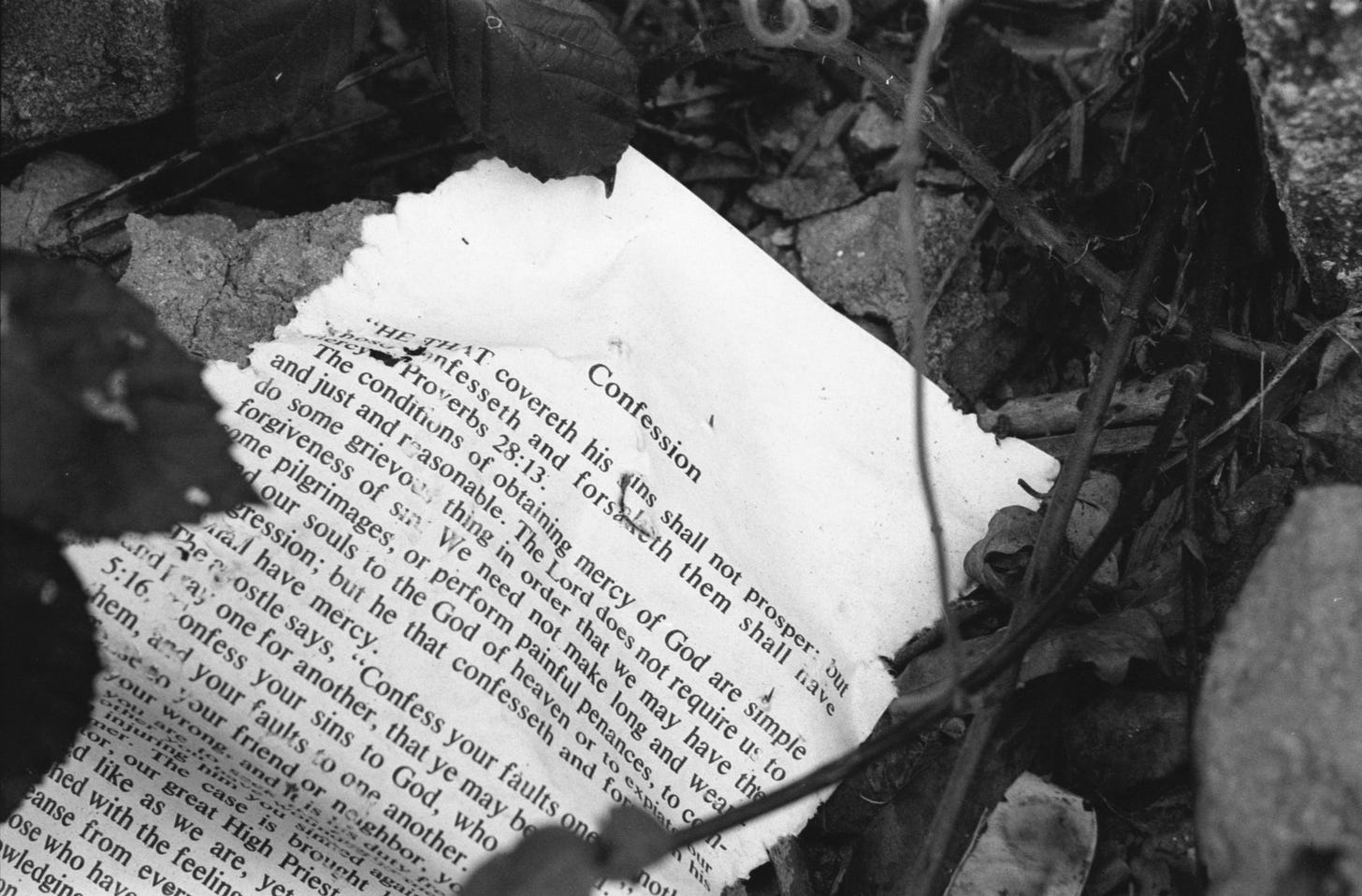

One might say the same about the history of liturgical reform: it seems to be the history of the degeneration of souls at prayer. The loss of Psalm 50 is representative of the loss of piece after piece, plank after plank, of the traditional Roman liturgy: we have seen the Church of Rome liturgically disintegrating. Pius XII demoted the Miserere in the reengineered Holy Week of the mid-1950s; it was further demoted in the rubrics of John XXIII, and still further in the new fleet of liturgical books launched by Paul VI—indeed, almost banished from the Liturgy of the Hours, in comparison to the central, or better, ubiquitous place it once enjoyed in the common prayer of centuries of Western Catholics.

One could compare to this denudation and evisceration of public prayer the parallel process by which the Eucharistic fast was emptied of meaning. Traditionally, it was from midnight on, because the Bread of Life should be the first food to enter one’s mouth each day, a view already well in place by the time St. Augustine describes it, and seen as well-nigh immutable by the time St. Thomas Aquinas is writing the Summa theologiae. Under Pius XII, it was reduced to an arbitrary but still somewhat meaningful three hours; under Paul VI, it was minified to a ridiculous and nugatory one hour before communion—which basically means, be careful not to scarf down a twinkie on your way out to the car.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.