N. C. Wyeth, Draftsman of Childhood Imaginations

Of ideals, imagery, and artists

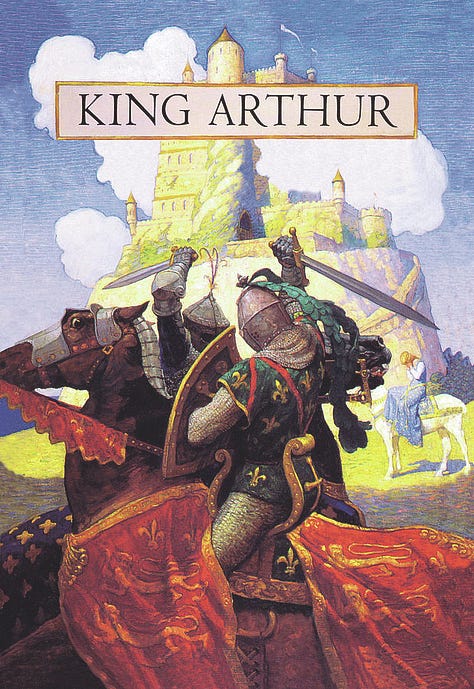

Billowing white clouds drift across a pastel blue sky, throwing a patchwork of soft shadows on the glistening leaves of trees. Above, an ivy-clad tower stands against the light-filled clouds, its warm rock shaded by their nebulous quilting.

A light breeze ruffles the dry grass with a sighing sound. Chests heaving and panting, their shining mail glistening, two knights pause in combat. Their sculpted muscles and clenched hands, their wide-footed stances, exude a sense of power, of intense strength — of energy directed, laser-beam-like, against the other. The jewel rich colors of the fighter’s tunics offer another visual point of tension: the strongest primary colors, blue and red, add their own force to the stand off.

This painting is one of a set of Arthurian illustrations by the American illustrator N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945). Entitled, “I am Sir Launcelot du Lake,” it depicts an encounter between Sir Lancelot, in blue, and the red-liveried knight Sir Turquine, who holds 64 knights and ladies imprisoned in the castle behind him. After hours of brutal combat, during which the backs of their steeds break, the evil Turquine proposes a truce and the release of his prisoners as long as his unknown combatant is not Sir Lancelot, the slayer of Turquine’s brother. Wyeth here portrays the fraught moment when Launcelot reveals his identity: “I am Sir Launcelot du Lake, King Ban's son of Benwick, and knight of the Round Table.” Launcelot then beheads Turquine since a truce is impossible.

Pyle and the Brandywine School

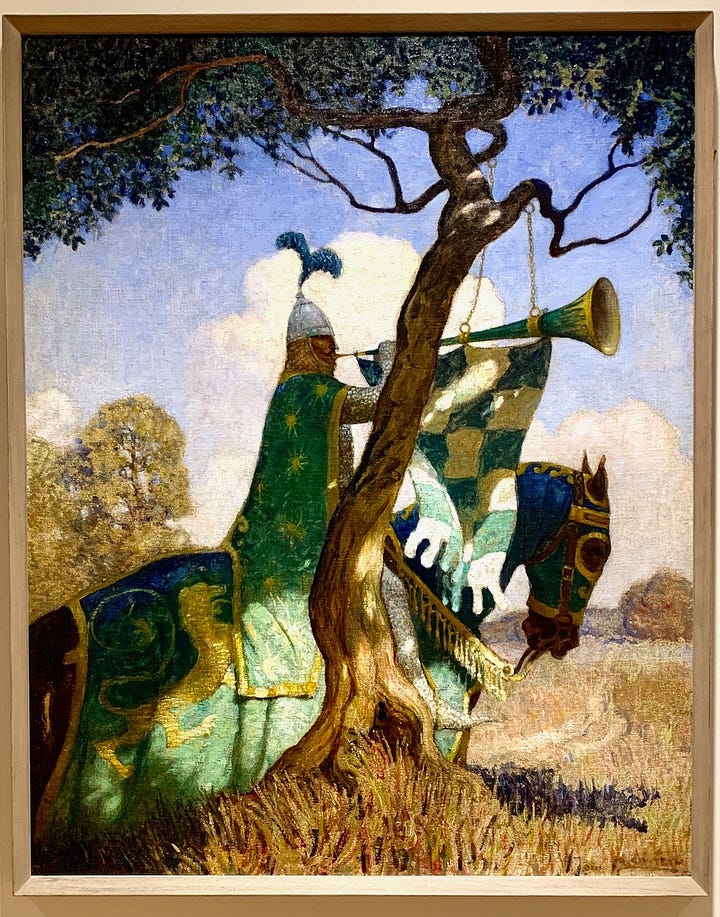

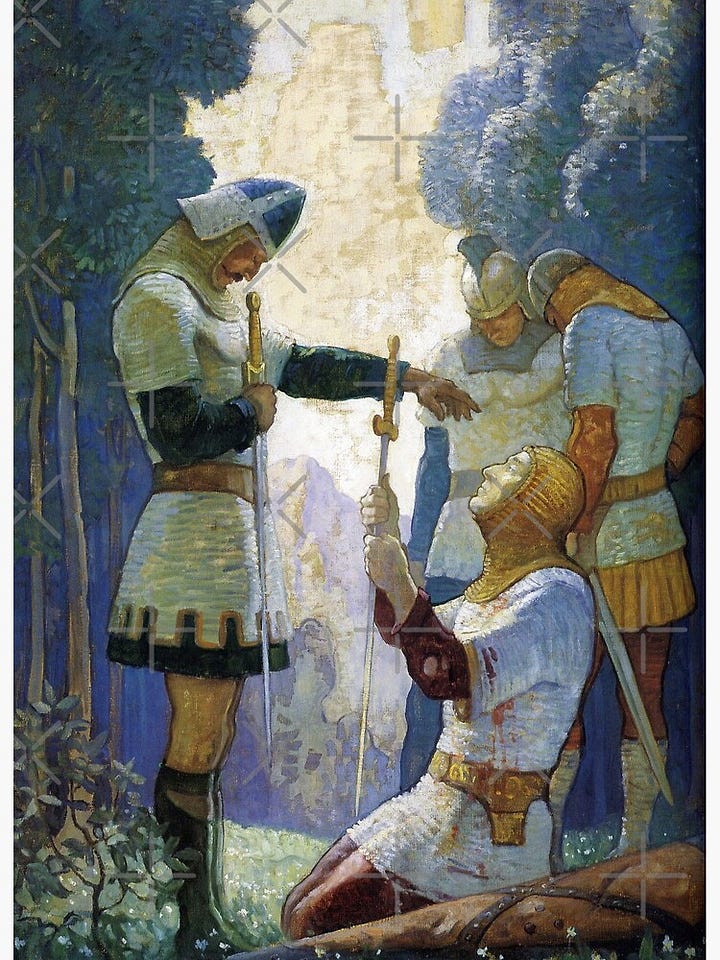

Wyeth, and his teacher Howard Pyle, are probably the most famous figures of a particular artistic movement: the so-called Brandywine school of illustration. Pyle developed the style and illustration theory which his students fostered, and so gave rise to both the artists’ community near the Brandywine river and a style which bore the same name. Illustrators of adventure novels, fairy tales like Robin Hood, and historical classics such as Homer’s Odyssey and the Arthurian legends, Pyle and Wyeth cultivated a simultaneously realistic and idealized vision of their subjects.

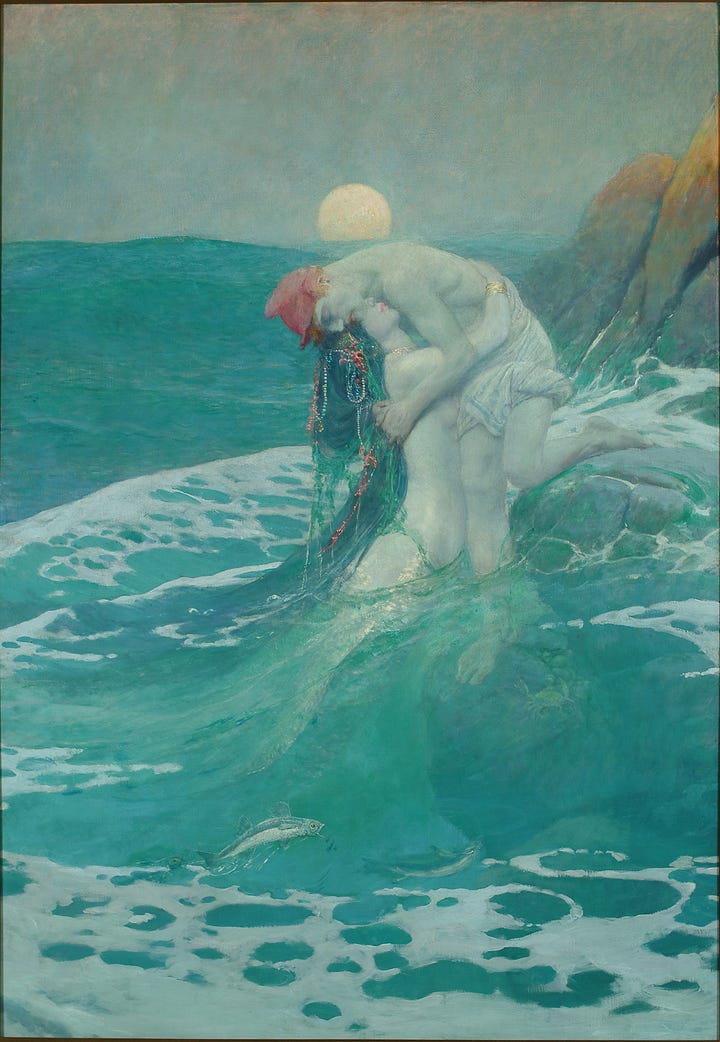

Characteristics of their paintings include bright colors and sharp contrasts, a generally naturalistic style combined with impressionist elements, and energetic, emotive figures. Pyle encouraged his students to spend time outdoors and paint from nature, and hoped that a truly American style could be developed, with fame and success for his artists not so dependant on having studied and made their names in Europe. Unlike the Pre-Raphaelite school, which espoused a highly polished and romanticised medievalism, Pyle and his students preferred a more rugged look, while also steering away from the highly stylized and sometimes sensuous Art Deco and Art Nouveau movements of illustraton.

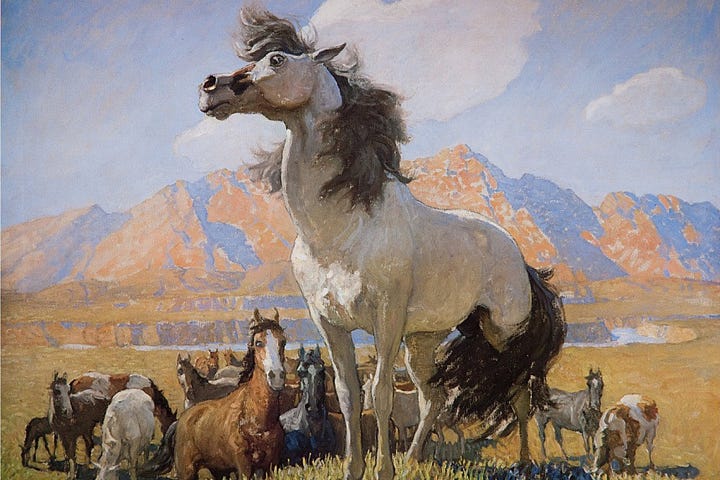

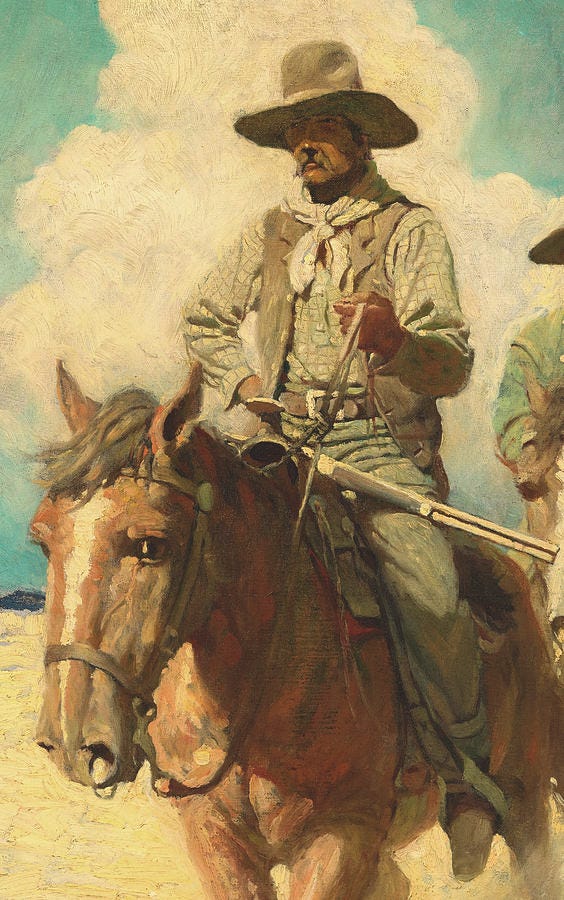

Pyle inspired a new generation of storybook illustration and, like other contemporaries of his, contributed to the revival and retelling of folk and fairy tales not only by painting but also by writing and publishing such stories. Pyle and his students embraced, in addition to the Old World story traditions, the Cowboy and Wild West as a unique and genuinely American source of similarly inspirational narratives.

The Adventurous Artist

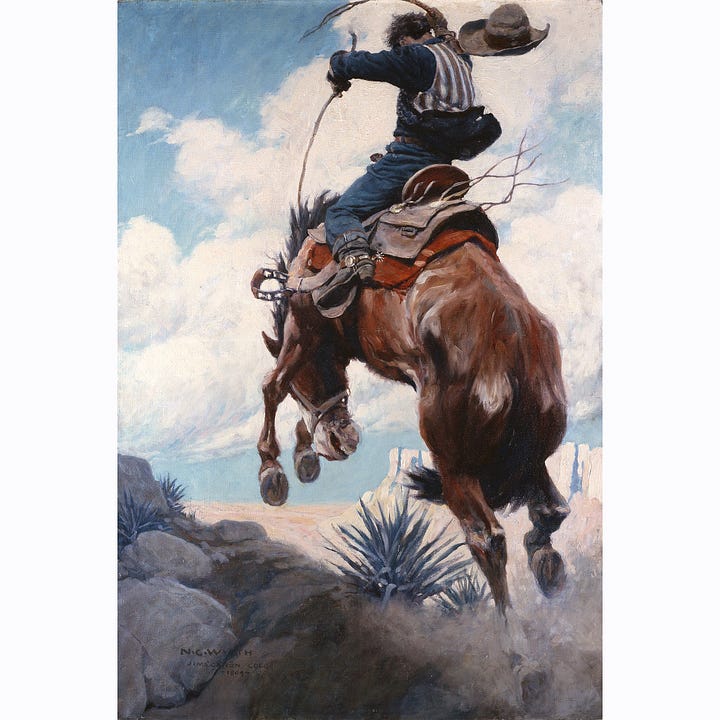

N.C. Wyeth grew up in rural Massachusetts, the oldest of four brothers immersed in farm life, fishing, hunting, and adventuring. Having studied art at several schools, he traveled to Pennsylvania to study with Howard Pyle in 1902, and in 1903—only twenty years old—he received his first major commission, a bucking bronco for the cover of the February 21st edition of The Saturday Evening Post. A year later, the same magazine requested illustrations for a Western story, and Pyle encouraged him to travel to the Wild West to gain firsthand knowledge of the Cowboys and Indians. This Wyeth did, working in Colorado as a ranch hand, as well as visiting New Mexico and Arizona.

Much like the adventurous Hilaire Belloc who had explored the Wild West a decade before him, Wyeth was not just a dilettante sitting in a studio painting a life he had never experienced. When his money was stolen, he had to work as a mail carrier riding between a New Mexico trading post and Fort Defiance, Arizona in order to pay for his fare back east. On another expedition out west, he learned about mining and collected artifacts and costumes of the natives and cowboys to bring back home. “The life is wonderful, strange,” he wrote in a letter, and “the fascination of it clutches me like some unseen animal — it seems to whisper, ‘Come back, you belong here, this is your real home.’”

Wyeth eventually moved away from Western themes and turned toward the illustration of classic literature, including Robinson Crusoe and Rip van Winkle. He also completed numerous illustrations for various magazines and ads for companies like Cream of Wheat and Coca-Cola. He lamented the commercialism upon which he became dependent to make ends meet, and in his non-illustrative work explored a wider variety of styles.

Ideals are Presented by Paintings, not Photographs

Growing up, I remember pulling from the living room bookshelf a large picture book of Robin Hood stories, as well as Arthurian legends, both filled with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth. The brilliant banners flying in the breeze, the slender maidens and large-shouldered knights, the twisted roots of trees and murky woods, still speak to me. Looking at them, I hear a clear echo of the lovely country of imagination, of what I might call the Land of Ideals.

Why are illustrations so important? Why are they formative for children? Do they convey something no other medium can? If so, how?

Fundamentally, I believe these questions gravitate around the fact that paintings, even when they are “from life” (as opposed to an imagined subject), convey more of an abstraction of the subject than an instantiation of the subject’s individuality.

Contrast this with photos: even the most idealized photographs are of specific subjects, not of abstractions. The purpose of much photo-editing and the staging of something like a fashion photo-shoot is to create idealized or archetypal photos… and yet it never quite works.

Why? Because however perfect the photo, at its root it is not a human creation, a synthesis and representation of human experience, but a mechanical replica of impersonal light. In contrast, a painting is a non-mechanical, man-governed representation of personal light — that is, light received, understood, interpreted, and adjusted by a human person.

The reason illustrations like Wyeth’s are important, then, for the formation of childhood imagination, is that they portray an idealized but unreal subject. Wyeth’s illustrations of macho cowboys inflame a boy’s heart with a yearning for greatness; but photographs of manly-man models convey a different spirit, at once tarnished by the lack of true manliness in the actual models themselves, and also filled with the potential for unhelpful self-comparison. The same is, of course, true for little girls. I suspect that photographs of “ideal women” lead to body image problems among ladies much more easily than paintings of ideal women do, for the simple reason that the one presents an “ideal” that is alive in our far-from-ideal world, while the other represents an ideal living in its own world, the world of ideals that speak of love, valor, danger, struggle, commitment, triumph.

When I speak of ideals and their presentation, I mean something rather specific in this context. I might define it thus: the aesthetic communication of moral, spiritual, and natural truths visually through fictional subjects. This usually involves a fictional perfection, emphasis, and clarity seen only dimly in our fallen world. Pyle and Wyeth provide abundant examples: their illustrations come from a world where all men are strong, all women are beautiful, all good good, and all evil evil. Their clouds are cloudy, their sunsets rosy, and sunlight thickly golden. Wise men have long beards, maidens flaxen hair, and children splash naked in the brooks. In other words, they communicate truth about reality by departing from reality—for every man should be strong, and if there are men who are not, one of their potencies has failed to be actualized, for one reason or another. This does not mean that the only important attribute of men is their strength or of women their beauty. Rather, it indicates that there are certain universals about reality (such as strength and beauty) which men have always found to resonate as archetypally true, even if reality does not always fully measure up to the archetype; and these archetypes, in turn, as often as not are meant as reflections of spiritual qualities like them, such as strength of character and beauty of soul.

The Double-Edged Sword of Ideals

Ideals are dangerous. They are a double-edged sword. If a child (or an adult for that matter) lives without ideas of ideal men and women, of ideal adventures, treasures, ships, guns, horses, robes, and golden crowns, he or she will have little to no imagination, a stale taste for wonder, and a lack of noble thumos or motivation to pursue the transcendentals. Often the formation of ideals is directly linked to the instinct for play, which is in turn tied to growth in morality and a host of other essential developmental stages. A child with no ideals is a failed child — and likely a failed adult too, if ideals are not acquired along the way. Indeed, I will dare to say more: show me a child without ideals, and I will show you an adult without life twenty years later. That is one edge of the sword: the decapitatingly dangerous prospect of life without ideals.

On the other edge of this sword, we have ideals which are too strong, imbalanced, or wrongly taught. That is where I believe photographs can be so poisonous. If a child (or an adult for that matter) imbibes photographs of ideal adventures, vacation homes, cars, food, and (especially) sexual attractiveness, he or she will, once again, have little to no imagination, a stale taste for wonder, and an inability to pursue the imperfect good which surrounds us.

The revolution whereby advertising and media in general were saturated with photos coincided with their sexualization. Coincidence? Who knows, but what we do know is that today false ideals kill the goods which in previous ages true ideals vivified. The false idealization of female sexual beauty — most obvious in photographic advertising for the fashion and cosmetics industry, from billboard ads to shopping-center displays to porn movies — has rotted in generations of men the ability to love selflessly and truly, and for generations of women their sense of self-worth, self-respect, and hope. The same is true, if less dramatically, in other sectors as well: the homepage of any travel agency, cookery website, or real estate broker proves my point. The hegemony of photography has pulled down the spiritual ideal and replaced it with carnal reductionism.

Of course there are painters who pursue false ideals, too; painters as much as photographers can veer into the pornographic. Perhaps our current crisis of false ideals could have been created with painted pigments instead of processed pixels, if cameras had never been invented. It is impossible to say for sure. My point is not that photography always produces false ideals and painting never does; but rather, that this special category of heroic ideals, as we see them brilliantly illuminated in the works of N. C. Wyeth, is almost solely, if not completely, communicable via artwork.

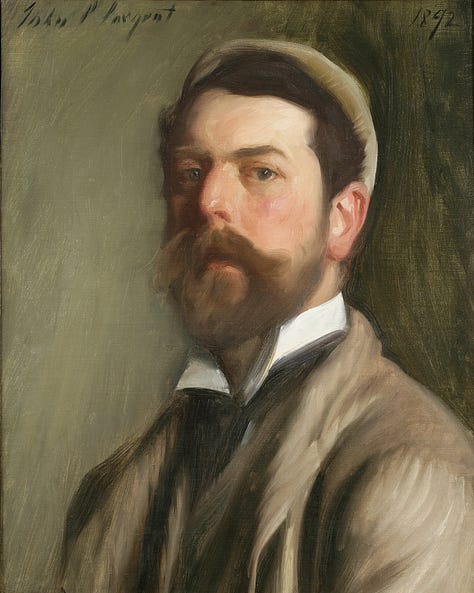

Even a painting carefully and accurately depicting a particular, real subject—such as a realistic portrait—presents a concrete instantiation through an interpretive angle. In this sense, the greatness of great paintings consists in what they choose not to show—or what they choose to emphasize—rather than in their exact representation of the surface of their subjects. Great portraitists such as Hans Holbein, Diego Velázquez, or John Singer Sargent communicated the rich personalities of their sitters. Argue, if you like, that great photographers can do this too — I am yet to be convinced, not that they are capable of artfully choosing, framing, and “capturing” their photos (they certainly are; one look at the work of Ansel Adams is enough to clinch that point), but that they are doing something in the same category of communication as a portraitist. And this, for the simple reason that it is not they but their machines which make the portraits.

Ideals as Blueprints

Thinking about words similar to or connoting “ideal” made me think of the way in which the concept of an ideal is closely related to that of “exemplar.” The plans or blueprints for a house, for example, are the “ideal” according to which it is to be built. Words such as mark, token, proof, example, indication, evidence, and sign all have the same mist hang ing around their shoulders.

Thus, with a Platonic twinkle in my eye, I would argue that the storybook world of ideals or perfect forms has something to teach us about reality, imperfect as it is, and about what plan or exemplar we should be modelling ourselves after. The leathery cowboy of the Wyeth illustrations is a token and example of manly strength, as the elegance and beauty of his medieval maidens communicate some real indication and evidence of womanly beauty through idealized marks and signs. The fact that Wyeth’s illustrations of battles and abductions, of heroes and villains, stir a thumotic longing in us for strength and beauty and nobility is proof of its affective effect on us through idealization.

As I said above when defining this idealism, things dimly seen are nonetheless truly there. Among other powers it has, Wyeth’s art speaks to the part of our heart that knows the world is drearier, uglier, less just, less right than it should be. These illustrations, like the stories they accompany, have something to say about the paradise we long for. Paradoxically, they capture both the wistfulness and longing of man — as when even the great Robin Hood dies — and his immortal aspirations and potential for superhuman greatness.

Artists like N. C. Wyeth have the potential to be draftsmen of childhood imaginations. Make sure books with illustrations like these are scattered abundantly around your home. Let us notch the glistening feather of his realistic idealism in the bows of our children’s imaginations so that they may have shafts to shoot — against the enemy, for the joy of marksmanship, and for the delight of maidens. May the mists and clouds, light and darkness of their lives be as thick as the brushstrokes on these canvases. “The life is wonderful, strange,” they will say as they discover the land of ideals. “The fascination of it clutches us like some unseen animal — it seems to whisper, ‘Come back, you belong here, this is your real home.’” And they will be right.

Reprinted Books with Wyeth illustrations

Disclaimer: these are editions I’ve been able to find on Amazon which contain Wyeth illustrations, but I haven’t seen any of the physical copies myself (the ones I read growing up were different editions), and therefore I cannot comment on the printing/image reproduction quality. Let us know what you think, if you end up acquiring one!

The White Company, a medieval novel by Arthur Conan Doyle

Thanks so much for reading! If you enjoy my work here on my dad’s Tradition and Sanity Substack, please consider giving me a small tip via my buymeacoffee.com page, where you can make a one-time or recurring donation to support my writing. Thank you!

Growing up, we had the entire series of the book House books. Over the years they were displaced and misplaced, which to me was a great loss for my family, which remains. Thanks for sharing your observations and thoughts.

The Hill School in Pottstown PA has a set of paintings used to illustrate the book “Poems of American Patriotism” published after WWII. They hang in the dining hall. One can’t look at them and not be moved.