Pius X to Francis: From Modernism Expelled to Modernism Enthroned (Part 1)

The backstory of a seductive arch-heresy and an attempt at a definition

If we wish to understand Pope Francis and the direction in which he has tried to lead the Church, it is not enough to look at Argentina, or the Jesuits, or the Second Vatican Council. We must step further back and take into view the problem — or, better, the plague — of Modernism. In order to impose limits, I will start with Pope Pius X at the start of the twentieth century. I assure you that, by the end of this three-part series, we will be in possession of a key for understanding the meltdown through which we are passing.

Last Day for Candlemas Special Offer!

Restoring all things in Christ

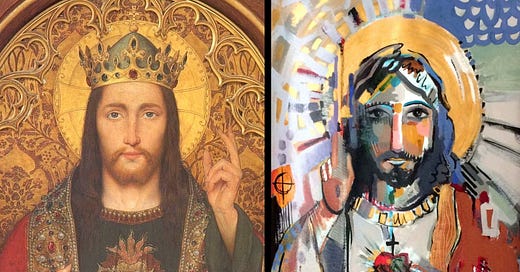

With his inaugural encyclical E Supremi of October 4, 1903, the Supreme Pontiff who succeeded Leo XIII eloquently outlined the program of the new pontificate: Instaurare omnia in Christo, “to restore all things in Christ.” As subsequent years would prove, Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto (1835–1914), who reigned as Pius X from 1903 until his death just after the start of World War I in 1914, committed himself bravely and energetically to this mission. Pius X looked with tender love on his flock, ready to guide it into pastures of sound doctrine and holiness, while he gazed out with anguish upon the ever-growing multitudes of unbelievers, lost sheep for whom he felt the Good Shepherd’s compassion.

The first pope in many hundreds of years to have been canonized (due to the lofty and stringent norms for canonizations in place before Vatican II), Pius X was singlemindedly dedicated to the reform of the Church, above all in her liturgical and devotional life.1 His writings indicate that he always considered the internal strengthening of the Church, the deepening of her life of prayer and sacrifice, to be her best and, in truth, her only safeguard against attacks from without and dissensions from within.

Pius X knew the fundamental importance of preserving and preaching the Catholic Faith in its purity and fullness, for this is the gift that the Church can give mankind. No matter how much the world changes in its structures, no matter what technology is developed and deployed, the human condition is ever the same: man the sinner is always in need of God’s mercy, always in need of the salvation Christ offers to us through the ministry of the Church He founded, and through her constant confession of the true religion revealed by God. It is in light of this stubborn adherence to the immutable essence of the Catholic Faith that we must understand Pius X’s battle against the “Modernists.”

More a miasma than a movement

Modernism was a complex movement that never had an official platform or a centralized organization; it was a loosely-defined set of tendencies and views, a method and a mentality, that criss-crossed the Catholic intelligentsia of Europe at the end of the nineteenth and the start of the twentieth centuries, casting a long shadow for many decades to come, down to the present day.

The Modernists believed that Christianity must be reinterpreted in accordance with the (perceived) discoveries and needs of the modern age. This, in turn, implies that Christianity is not a religion revealed by God but a product of human minds cogitating on divine subjects, and therefore mirroring the evolution and vicissitudes of human thought and experience.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.