Rounds, Grounds, and Other Forms from Four Composers

A wild ride through 700 years of English music

Each country has its distinctive musical tradition; England’s is one of the richest. Continuing my exploration of various periods and styles of music, in this article I’ll take you through 700 years of English music by introducing you to four musical giants: John Dunstable, William Byrd, Henry Purcell, and Benjamin Britten.

With each composer, we’ll examine a particular technique that his piece might be said to epitomize. Buckle your seatbelt—it’ll be a wild ride!

John Dunstable’s Sweet Thirds and Horoscopes (15th Century)

A transitional figure between the medieval and Renaissance periods, John Dunstable (c. 1390-1453) is the most famous English character in late medieval music. Almost nothing is known about his life, although it seems he was not a cleric, which was unusual for most of the musicians in his day.

Dunstable was likely a married man, and upon his death was eulo gized not just as a musician but as one well-versed in mathematics, astronomy, and even astrology. One manuscript contains astrological drawings which may be by Dunstable himself, and another contains copies of Boethius’ De musica and De arithmetica, both of which appear to be copied in Dunstable’s hand, along with various excerpts on horoscopes.

I love stumbling upon interesting details about medieval lives. Rodney M. Thompson notes in the Winter 2009 issue of The Musical Times that “Dunstable was in the service of Joan of Navarre, Henry IV's second queen, probably from not long after her husband's death in 1413. He is known to have received from her a valuable cup as a New Year’s Day gift in 1428...”

Dunstable’s influence stems primarily from his use of the contenance angloise or “English manner”, a polyphonic style in which the harmonies are based on the consonant third and sixth. On the continent, thirds and sixths had been generally frowned upon due to medieval theories of musical mathematics: the intervals were not as “pure” in their ratios as octaves, fourths, and fifths. This innovation of broadening the harmonic palette was hailed as strangely sweet by continental ears.

Notes Thomson drily: “Dunstable is a rare example of an English composer who impressed the French,” and this is encapsulated in the origin of the term contenance angloise itself, coined by the French poet Martin le Franc when describing the music of the early 1400s to Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy:

They [the French composers Du Fay and Binchois] took on the guise

of the English [contenance angloise] and follow Dunstable and thereby a marvelous pleasingness makes their music joyous and remarkable.

You can hear these intervals in one of Dunstable’s famous motets, “Quam Pulchra.” Bar 1 opens in unison before the top voice jumps to a third (C and E); then the next chords in measure 2 both consist of thirds and sixths, and so on:

Cantus Firmus

One unique medieval technique which died out during the Renaissance is the practice of singing different texts at the same time, giving vocal lines their own (and somehow related) words. Dunstable masterfully sets the Pentecost hymn Veni Creator Spiritus over the top of the Pentecost sequence Veni Sancte Spiritus. Note the lower two voices carrying the hymn text in slow motion, while the upper voices dance with the more wordy Sequence.

Following the practice of cantus firmus, the lowest voice takes the melody of the chant, lengthens it, and then breaks it up as necessary in order to fit with the rest of the polyphony. I’ve marked an especially clear passage below: the highlighted notes in the score to the left match the pitch changes of the same phrase in the chant to the right, but slowed down and sometimes broken with a rest:

Harry and Lizzie’s Tunes (16th Century)

The 16th century is so rich in composers it seems a crime not to mention more—from Byrd and Tallas to Dowland and Gibbons. Byrd takes the prize, though, and provides an excellent opportunity to discuss rounds or canons. Before we get there, however, I think a brief word is in order on the two English monarchs who dominated that century, both of whom were intensely musical and somewhat insane.

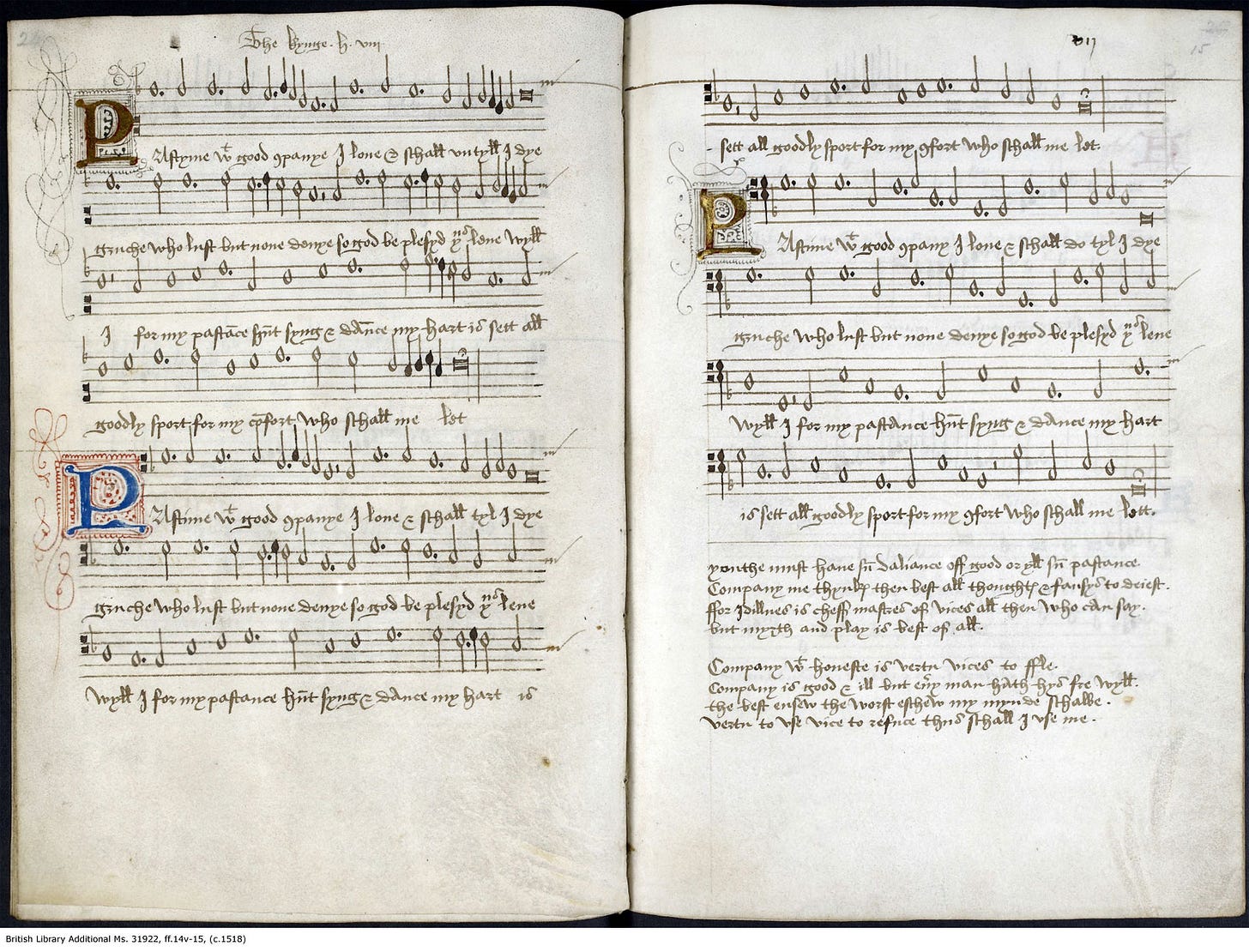

Henry VIII was a skilled musician, singing and playing the lute as well as various keyboard instruments. A few songs are even attributed to him, the most famous being “Pastime with Good Company,” also known as “The King's Ballad.” This ballad describes the leisurly activities of the court, including singing, dancing, and hunting. Henry praises these “pastimes with good company” as a remedy for vice which flows out of idleness. (It’s not entirely convincing as autobiography, but we’ll let that pass.)

In the concert below, “Pastime with Good Company” recurs in between other music likely heard at Henry’s court:

Henry’s daughter by Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth I, also played the lute. During her reign the High Renaissance in England was in full swing: from Shakespeare to Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes, the island of England was teeming with great minds — and fine musicians. Many compositions were written to flatter her, and she was graced with numerous literary allusions — often referenced as one or another Greek goddess (good insurance at a time when monarchs were very much inclined to send anyone who displeased them to the gallows).

In this hilarious madrigal by Thomas Wilkes, the lyrics speak of Vesta, the Roman goddess of the hearth, meeting the maiden queen “fair Oriana” (wink for Elizabeth, the so-called “virgin queen”) along with a company of Diana’s nymphs and shepherds.

As Vesta was from Latmos hill descending,

She spied a maiden Queen the same ascending,

Attended on by all the shepherds' swain,

To whom Diana's darlings came running down amain,

First two by two, then three by three together,

Leaving their goddess all alone hasted thither;

And mingling with the shepherds of her train,

With mirthful tunes her presence entertain.

Then sang the shepherds and nymphs of Diana,

Long live fair Oriana!

The madrigal includes numerous instances of “word painting,” where the music somehow mimics what the lyrics are speaking of. For example, when Vesta descends, the tunes flow downward; when the characters ascend, so does the music. Even more clearly, on “first two by two,” only two voices sing: “then three by three” is a trio, and when they leave “their goddess all alone,” the soprano sings it…all alone. Voces8 sings it here from memory with lots of hammed up rhetorical gestures!

Rounds of Canons

Back now to the avian songster. Byrd excelled in compositions of great complexity, from polyphonic Masses to instrumental fantasias to keyboard dances. His musical genius also allowed him to do something deceptively simple: com pose excellent rounds.

A round or canon is a composition in which a single melody, sung by people entering at different times, lines up in a way that harmonizes. The melody of a round is composed having in mind how it will overlap on itself, so that contemporaneous notes in later measures will correspond well with the earlier measures they are sung on top of.

Byrd did not invent rounds: they are very ancient, and in fact the earliest extant piece of music in English is a form of round—“Sumer is icumin in,” pictured as the background in the header to this article (listen to it here). Perhaps the best-known round to English-speakers is “Row, row, row your boat.”

“Non Nobis, Domine” is a round sometimes attributed to Byrd. I include it here since it’s very simple to grasp: below you can see that the 1st and 3rd voices sing the same melody, at the same pitch, six beats apart, while the middle voice sings the melody transposed down a fourth but otherwise unchanged, starting two beats after the first.

Here it is, sung with the score:

Rounds or canons don’t need to be as simp le as that, however: they can be combined with other elements to yield a more complex whole. In “Miserere mihi Domine,” a Compline antiphon, Byrd hides a canon and a cantus firmus among other polyphonic voices which are neither.

In yet another virtuosic piece of part-music, Byrd includes a quotation from Greensleeves, a galliard (triple-time dance) section, and segments of a canon. The imitative entrance at the beginning is clear in the 1st and 4th lines:

The canon isn’t strict in this piece, but there are many instances of canon-fragments being worked into the texture to enrich the piece:

This recording, however, is my favorite: with extra instruments added to the consort, the sound is especially full.

Groovy Grounds with Henry Purcell (17th Century)

A “ground” is a composition built upon a repeating bass line, over which the composer cleverly writes changing upper lines, defying the repetition of the bass with his inventiveness in the vocal line and sometimes tricking the expectation of the listener by making the natural cadence of the “ground” occur in the middle of a phrase in the melody.

A visualization will help. In Henry Purcell’s aria “Dido’s Lament,” the “ground bass” is ten notes long: G, F sharp, F, E, E flat, D, B, C, D, G. (Sometimes Purcell will break the penultimate D and drop it an octave, but that doesn’t really change the harmony). The yellow highlight is the ground’s first appearance, the green it’s second iteration, the blue its third repeat, and so forth.

You can see that the voice comes in with the beginning of the bass in measure 14, but it starts over again in the middle of the same sentence in measure 19.

This aria is from Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas, based on Book IV of Virgil’s Aeneid. A tragedy, the story deals with the love of Dido, the Queen of Carthage, and her despair when her lover, the Trojan hero Aeneas, abandons her to go and found Rome. It is Dido’s last aria, in which she speaks of her imminent death through heartbreak: in the proceeding “recitative” (music sung quickly, like speech, in an opera), she says to her servant Belinda that death is a welcome guest, before launching into the aria where she asks to be remembered but her fate forgotten (at that point the ground bass starts):

Recitative Thy hand, Belinda, darkness shades me, On thy bosom let me rest, More I would, but Death invades me; Death is now a welcome guest. Aria When I am laid in earth May my wrongs create No trouble in thy breast; Remember me, but ah! forget my fate, Remember me, but ah! forget my fate.

The ground highlighted above is highly chromatic, giving a feeling of floating darkness. The commentary provided by the ensemble Voices of Music is enlightening:

The meter and lines of the opening recitative are striking: four fragmented lines of text with syllables of nine, seven, eight and seven are reinforced with mismatched words which do not easily form a meter, creating a metrical dissonance; the disintegration of the formal conventions of poetry mirrors the imminent destruction of Dido. The tension and dissonance of the conflicting meters and lines is only resolved in the last line of the aria, which is classical iambic pentameter: "Remember me, but ah! forget my fate." The repetition of the last line creates the impression, both musically and textually, of a heroic couplet, accentuating the closure of Dido's final scene.

Here is their striking performance:

With Dido, the dissolution is subtle. In another work by the same composer, a weirder tactic is adopted. In Purcell’s 1691 opera King Arthur, the spirit of winter appears and sings an aria in which he describes his frozen state, and asks why he has been awakened. As it turns out, it is Cupid who will melt him, and the winter spirit or “Cold Genius” (like genie) admits that he has been warmed by love. Before that, however, the cold spirit complains of being wakened:

What power art thou, who from below Hast made me rise unwillingly and slow From beds of everlasting snow? See'st thou not how stiff and wondrous old, Far unfit to bear the bitter cold, I can scarcely move or draw my breath? Let me, let me freeze again to death.

The vocal line is broken like someone panting, with the strings shivering an accompaniment both weird and awe-inspiring: here’s countertenor Andreas Scholl’s masterful rendition:

This cold song is also a ground. But let’s end on a more upbeat note (Purcell was quite capable of this!). Here’s a third ground, “Here the Deities approve,” describing a mythic paradise, a “great assembly of Apollo's race.”

Here the Deities approve,

The God of Musick and of Love,

All the Talents they have lent you,

All the Blessings they have sent you,

Pleas'd to see what they be-stow,

Live and thrive so well below.

Countertenor Reginald Mobley (a Grammy-nominated singer) does a superb job here with theorbist Brandon Acker:

Benjamin Britten (20th Century)

My next British composer leads in a funny way directly from Purcell: the main composition of his that we’ll look at here is based on a theme of Purcell’s. As a modern composer, he will provide some good variety among all this early music!

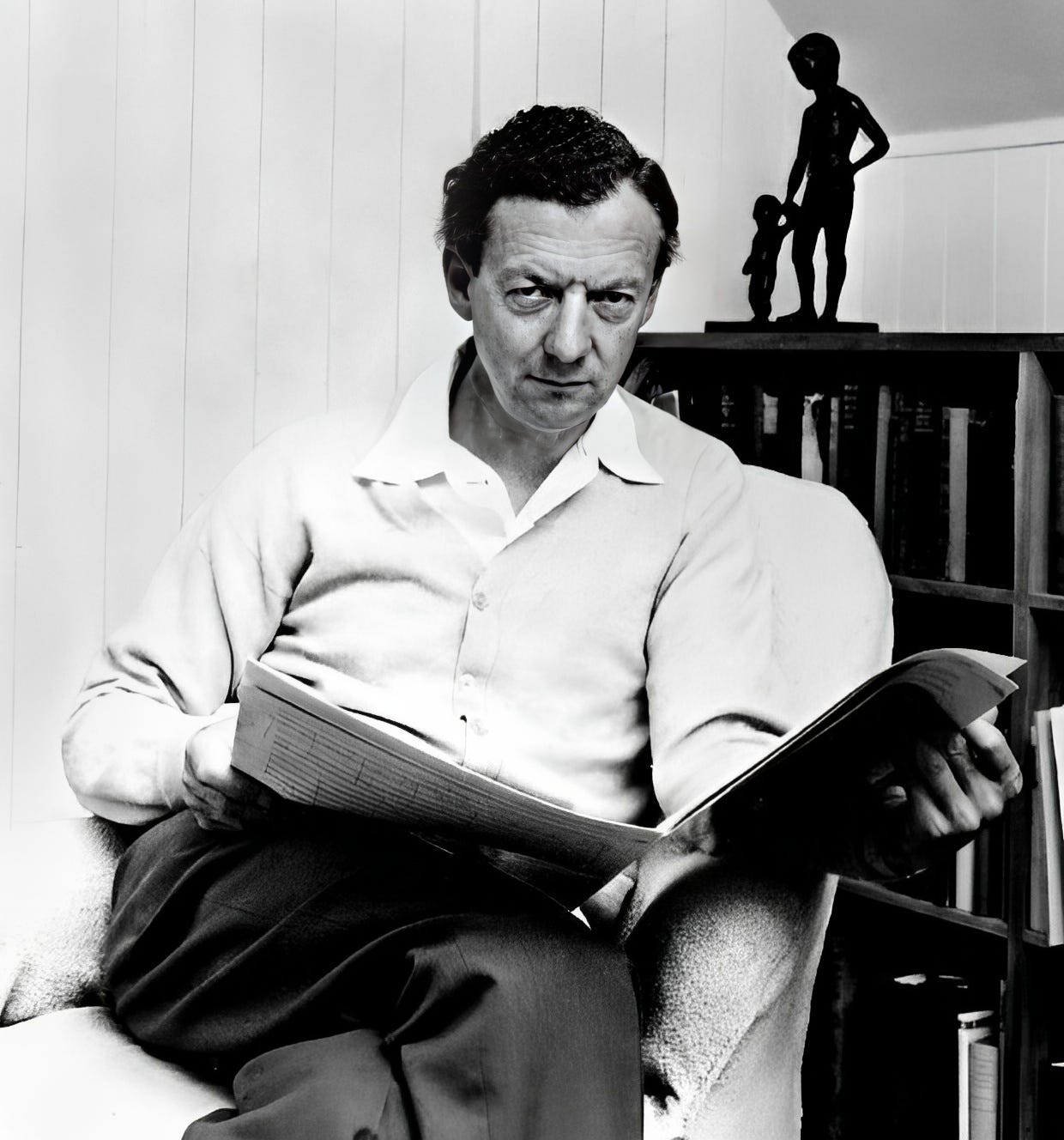

Benjamin Britten was born in Suffolk, England, in 1913. A fairly ordinary boy in the English school system, he was musical from an early age, studied at the Royal College of Music, and subsequently pursued a career which spanned America and England. A pacifist, he spent a large portion of World War II in America, but finally gained exemption from military service in England.

He composed operas, song cycles, symphonic works, and chamber works, and founded the Aldeburgh Festival, now a world -famous classical music gathering. His War Requiem was commissioned for the reconsecration of Coventry Cathedral, destroyed during World War II: it intersperses traditional Latin requiem texts with poems by the poet-soldier Wilfred Owen, killed in action just a week before the armistice of World War I. It’s not a work I’m very familiar with and one I’d like to study more. A video of Sir John Eliot Gardiner conducting it in 1993 can be found here. Gardiner is a brilliant musician who stumbled into conducting while studying history and subsequently was knighted for his achievements in that domain. The concert attire is very old school; the entire orchestra in tuxedos is hardly seen today.

Benjamin Britten often composed with particular musicians in mind, including Julian Bream, one of the early pioneers of playing the lute in modern times. Britten's father refused to have a gramophone or radio in their house, making our composer one of the last to be brought up exclusively on live music.

Theme and Variations

A longtime concert favorite, the title of Britten’s The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra tells you most of what you need to know about the piece.

With a subtitle “Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell,” Britten’s 1945 Op. 34 is a playful romp through the various instruments of the modern orchestra. Musically based on Purcell’s Rondeau from the Abdelazer Suite, the opening of Britten's work is a nearly e xact replication of the Baroque piece. It quickly descends into modulations that are unmistakably modern, before entering on a theme and variations cycle that moves through individual instrumental sections — winds, strings, harp, brass, percussion. The specific groupings of variations start with the higher instruments of a particular category and move to the lowest; thus, for the strings, he starts with the violins and ends with the double-basses.

This piece was originally commissioned for a film with the same goal as the title suggests, and you can listen to the music with the charmingly old-fashioned original narration here (read by none other than Sean Connery of James Bond fame). The performance version, without narration on top of it, is slightly different and, not surprisingly, more often performed in the concert hall.

The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra entered the musical imagination of modern times to the point that there have even been two Jazz “parodies” of it: one by Duncan Lamont and the other by Mike Westbrook. For those with an affinity to jazz, you can catch some of Lamont’s version here.

The final component of Britten’s effervescent work is known as a fugue. Similar to the round or canon, a fugue is a composition that involves multiple lines imitating each other with music based on the same melody — the fugal melody. Sometimes the repetitions overlap, sometimes they are transposed, sometimes they get modified. In Britten’s piece, the fugal melody is rather dizzying and quite different from the majesty of the Purcellian theme. With his usual musical brilliance, Britten then combines the two, overlapping the fugue on top of the theme.

I’ll have more on Britten in another piece, but for now you can become a child again if you need a refresher on your orchestral instruments!

Thanks for joining us on this romp through the musical fields of Merry England. Let us know in the comments what you think of the music and if the score illustrations were helpful and contributed to your enjoyment of the music.

In consideration of the work that went into this article, musical research, diagrams, and voiceover recording with samples, please consider putting $5, $15, or $25 in my tip jar:

A big thank you to those who have donated in the past—I truly feel that my writing has been seen and is appreciated!

Good job, from an MA in musicology.

Also recommend the late Jeff Buckley's 'cover' of Dido's Lament--a testament to the breadth and depth of his talent.

Reading a little late here, but I really enjoy these articles that focus on music. Thank you, Julian! Not only is it wonderful being introduced to different kinds of forgotten, good music, but it is interesting as well.