The 150th Birthday of a Musical Revolutionary: Arnold Schoenberg’s Journey to Atonality and Why It Matters

(Those who are receiving this article by email or viewing it on Substack: please note that the voiceover includes all the musical excerpts, cut to the right length [and believe me, that’s particularly important for THIS composer], and so will doubtless prove a more enjoyable way of engaging with this content! — PAK)

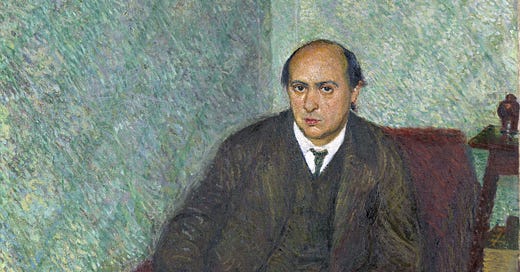

September 2024 is marked by two major anniversaries of two influential Austrian composers. Earlier this month fell the 200th birthday of Anton Bruckner, about which I wrote here. Just a few days ago — Friday, September 13 — fell the 150th anniversary of the birth of Arnold Schoenberg, in Leopoldstadt (the second district of Vienna) in 1874.1

More than any other figure, he was responsible for winning converts to the peculiar form of musical rationalism known as dodecaphonic atonality, which — strange as it seems today, when new music for the concert hall is overwhelmingly tonal — dominated art music for about seventy years.2 “Ich liebe meinen Gedanken und lebe für ihn!” (“I love my thought and live for it.”) These words are sung by the character of Moses in Schoenberg’s opera Moses und Aron, libretto by the composer. The opera is an inverted allegory in which Moses, the law-giver, represents the modern composer who, rather than receiving a law from nature or God, creates his own law and tries to impose it on the people — but ultimately without success.

Whenever I taught music to college students, they always cringed and groaned when I played atonal music to them, but I told them it was good for them to know how even the most unnatural and ugly things can become established by intellectual fashion and enforced by the systems of patronage and prestige. Plus, it was a lot of fun to see their reactions! Most of you will undoubtedly react in the same way. I will subject you to only a minute or two of the worst pieces — just enough to offer a suitable example of whatever is being discussed. Persevere: I promise that this article has a lot to offer in regard to the philosophy and theology of music.

Youthful romantic works

Early in his career, Schoenberg wrote lovely music. For instance, his string quartet in D major (1899), hints at the grace and playfulness of Schubert, and a very famous string sextet Verklärte Nacht [Transfigured Night], Op. 4 (also 1899), has moments of exquisite lyricism that earned it a place in the repertoire. Here’s a Notturno for Strings and Harp from 1895–96:

The early works of Schoenberg’s disciples Alban Berg and Anton Webern were not dissimilar.3 Berg composed Lieder in the style of Strauss’s Four Last Songs and a piano sonata whose intricate lines evidence a high degree of contrapuntal skill. Webern composed a set of Lieder not unworthy of Hugo Wolf, a quartet movement bursting with Wagnerian pathos, and a Passacaglia which could have been Busoni’s or Reger’s. In high school, I gave a Lieder recital in which I sang Sommerabend from Webern’s Eight Early Songs for voice and piano (1901–04), performed here by a contralto:

One can understand why Gustav Mahler initially supported the endeavors of Schoenberg and his circle. Later on, however, Mahler, who remained committed to the Romantic tradition even as he bade it a pained farewell, was to find it impossible to come to terms with the musical language of the works Schoenberg published shortly before Mahler’s death in 1911.

Extreme chromaticism

What happened between 1899 and 1911? The answer has its roots in the quintessential high romantic opera, Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, completed in 1860 and premiered in 1865. To depict every shade of sensual love and touch every emotion from the tenderest to the most passionate, Wagner employed a style more fluid, more chromatic, than any composer had ever done, using murky dissonance and the urge for its resolution in a ceaselessly spiraling pattern to build up tension and induce an hypnotic atmosphere of yearning.4 Postponement of harmonic resolution, a poignant symbol of frustrated love, is carried to enormous lengths; tonality hangs on the brink, ready to collapse into chaos.

In the operas that followed, Wagner stepped back somewhat from the harmonic experimentation of Tristan in order to concentrate his attention on refining other elements of music drama, such as maximizing the variety and variability of leitmotifs, incorporating “academic” counterpoint, and employing diatonic melodies orchestrated with unexpected economy. In his last opera, Parsifal (completed in 1882), are found passages of a simplicity and tonal clarity far removed from the dense fog, provocative sensualism, and mental agony of Tristan.

Yet it was not from Parsifal’s reassertion of triad and chorale but from Tristan’s amorphous opulence that Schoenberg took his stylistic point of departure. The chromaticism and formal experimentation of his early works went beyond the already remote Wagnerian boundaries, as can be heard in his String Quartet No. 1 in D minor, Op. 7 (1905), a tone-poem full of disjointed phrases, nervous twitches, and a dizzying loss of tonal centeredness:

The birth of “free tonality” is often presented as a breakthrough that occurred at the level of cerebral problems and solutions, but more was involved in the genesis of this quartet than intellectual free play. Jottings in the composer’s 1904/05 sketchbook concerning the emergent Quartet No. 1—“rebellion, defiance, longing, enthusiasm; feeling of oppression, despair; fear of being engulfed . . . extreme sensual intoxication” and so forth5—suggest that the style of this work was, in addition, the outcome of psychological and moral crisis in Schoenberg’s private life. This was in fact the case, not only for this quartet, but for many later works as well.6

Expressionism

In 1907, Schoenberg experienced a sort of musical nervous breakdown, becoming convinced that the romantic style had been exhausted. If music was to move beyond hackneyed conventions, a totally different path had to be staked out. Schoenberg asked himself: Why should dissonances be resolved at all? Why not let music wander in and out of tonality, like a dream in which events have no particular order or logic? Wouldn’t this allow the composer to express his immediate thoughts and feelings, whether they are coherent and beautiful or not? This artistic attitude is appropriately called “expressionism.” In such music, the use of key signatures and their inherent hierarchy of tones would be superfluous.

Thus, in the final movement of the String Quartet No. 2 in F# minor, Op. 10 (1908), Schoenberg omits a key signature, writes music with no reference to key, and introduces a soprano soloist who makes her entrance with words well suited to the nebulous, disoriented sound-world: “I feel the air of another planet. The friendly faces that were turned towards me even lately, are now fading into darkness. The trees and paths I knew and loved so well are barely visible. . . .” The poem closes: “I am afloat upon a sea of crystal splendor, I am only a sparkle of the holy fire, I am only a roaring of the holy voice.”7

Music’s “emancipation” from tonality was, so Schoenberg felt, the sole path open to a solitary creator facing the bankruptcy of late Romanticism. This idea could only have been entertained by one who believed that tonality is conventional, subjective and relative, not objective and absolute—in other words, that music is pure artifice, a work of mind and mind alone. If this were true, the composer confronted with blank paper would seem to have the frightening task of creating his work, his sound world, ex nihilo—a task doomed to failure from the start. With art no less than nature, ex nihilo, nihil fit. No creature can create, in the strict sense of the word. The gift of being, pure and simple, no less than the natures which receive being, are the work of the Divine Artist alone; the human artist can only make things, employing forms and materials from the world around him and within him.8

However, human artistry includes not only the godlike power to inform with a new order and reform an existent order, but the demonic power to deform and disfigure. In a letter written to a critic, Tolkien observed that in his fictional world, as in our real world, the forces of evil cannot create, they can only maim what has already been made, citing Frodo’s words to Sam: “The Shadow that bred them can only mock, it cannot make real new things of its own. I don’t think it gave life to the Orcs, it only ruined them and twisted them.”9

If we exclude certain pranks of John Cage, no composer has yet succeeded in writing a piece that altogether dispenses with the ingredients of rhythm or pitch; a composer is already fundamentally limited by his materials and their intrinsic potentialities. The only question is whether he will use them well or poorly. It is for the same reason that no painter has yet invented an image whose elements bear no resemblance whatsoever to elements encountered in the world.

As time was to prove, Schoenberg’s newly-discovered planet, though it has plenty of space for explorers, is inhospitable to normal human life.

“Free atonality”

The earliest “free atonal” works not only sound alien but take alienation as their theme. The monodrama Erwartung, Op. 17 (1909) depicts a lone woman wandering in a forest, madly searching for her lover, whom she finds dead near the house of the woman who stole him from her:

Donald Jay Grout defines the subject matter of atonal expressionism to be

man as he exists in the modern world and is described by twentieth-century psychology: isolated, helpless in the grip of forces he does not understand, prey to inner conflict, tension, anxiety, fear, and all the elemental irrational drives of the subconscious, and in irritated rebellion against established order and accepted forms.10

The compositions of 1909 “show Schoenberg struggling to break free from the functions and hierarchies of the tonal system and the extended, balanced forms it implied, and seeking an inner language, where all certainty is lost and the ego enters into crisis.”11 Pierrot lunaire, Op. 21 (1912), the best known of Schoenberg’s pre-dodecaphonic works, has been described as “the bizarre stories, melancholia and jokes of a disintegrating personality.”12

The technique of half-singing, half-speaking, called Sprechstimme, was to become a favorite device of the musical modernists.

Schoenberg, Kant, and Descartes

Many are the parallels between Schoenberg’s eventual aesthetic theory and Kant’s subjectivist account of the beautiful and, more fundamentally, that strain of phenomenalism or idealism traceable to Kant, who writes:

A judgment of taste is an aesthetic judgment, i.e., a judgment that rests on subjective bases… in thinking of beauty, a formal subjective purposiveness, we are not at all thinking of a perfection in the object.13

When we speak of “the beautiful” as if it were objective, we are merely voicing how we are affected by the presentation; the mind “feels its own state,” it issues a reflexive statement about itself, it remains wholly indifferent to the object’s existence.14 The Kantian divide between the world in itself and the world as we experience it—between an unknowable thing and a knowledge believed, with a kind of faith, to be still a knowledge of things (thus allowing one to grant legitimacy to the natural sciences)—deepens further the Cartesian dichotomy of soul and body, consciousness and a res extensa not reducible to consciousness.

This basic dichotomy in place, there is no end to the process of divorce: concept and emotion, knowledge and feeling, law and spontaneity, all are placed at odds, without possibility of reconciliation. A false anthropology can never bring these spheres together. The one or the other tends to be enthroned as “real,” the contrary being held to be reducible to the one so favored: the really real is the bodily, the res extensa, while consciousness or thought is an epiphenomenon of matter (Cartesian dualism’s atheistic-positivistic side); or the really real is consciousness, the self-defining self-enclosed world of thought, while matter, and everything having to do with bodies and my body, is projected by consciousness (Cartesian dualism’s phenomenological-idealist side). From the latter perspective, it begins to seem as though emotion or feeling were nothing other than a dim echo of intellection, burdened by a vulgar attachment to the here and now. Things like whistling and dancing are entirely here-and-now events having no other purpose than delight, which makes them very suspicious to an earnest rationalist.

The legend that an ironic Queen of Sweden charged Descartes with the task of composing verses for a court ballet (La naissance de la paix, performed in Stockholm, December 1649) because he himself refused to take part in the dance is something one wishes could be true, since, in a way, it encapsulates the fundamental problem of Cartesianism. Dancing is done in company, with music, and the whole body is involved; penning a text, like solving an equation, is the detached occupation of an intellectual sitting at his desk.15

Schoenberg took his stand first on one side of the Cartesian divide, then on the other, thereby demonstrating their hidden kinship, a false extreme’s uncanny ability to flip into its contrary. In the large-scale works of his ‘romantic’ period—the tone-poem Pelleas und Melisande (1902–03), the cantata Gurrelieder (1900–1911)—the style is hyper-emotional and self-indulgent, the music heaves and lurches, a barely-controlled outpouring of sound. One misses a luminous architecture, a sense of underlying gravity, an informing soul-principle. A composer who keeps going in this direction might end up thinking tonal music itself is somehow at fault and has to be deconstructed or denied, much as a man of loose morals can easily turn misogynistic, though the fault is in him, not in woman.

Here's a snippet of the Gurrelieder conducted by Sir Simon Rattle:

The spirit that denies

An eccentric modern composer, Kaikhorsu Sorabji, on the last page of a gigantic work called Opus Clavicebalisticum, scribbled “The spirit that denies!” underneath an excruciating chord combining all twelve tones of the scale played fffff [fortississississimo]. This motto could be taken as archetypal of music that scorns tonality: it is spirit denying flesh, at the expense of its own fullness of being, for although one might think that a chord comprising all twelve tones would say more than a chord comprising three or four, the exact opposite is true: the triad in its clarity, or any chord in which the inner relationships of the scale are respected, can speak of infinitely many things, whereas all the notes played at once speak only of mud and noise. The same mistake can be seen in the naïve child who thinks that if blue and yellow mixed together make so beautiful a color as green, then all the colors mixed together will make the most beautiful color of all.

Contrast this with the grinding polytonal chord at the climax of the third movement of Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony. Here we have dissonance, but placed in context, for a lofty and intelligible reason: the anguish is taken into the innermost heart, borne heroically, and finally answered in the still, small voice of God. There is exhaustion, but also liberation; defiance, but also submission. (If you want to hear that amazing minute from the 9th’s Adagio, I’ve cued it up here.)

The spirit of denial invoked explicitly by Sorabji and implicitly by many a modern composer is another name for the devil, whom St. Ignatius of Loyola described as “the enemy of human nature.” Ignatius here spoke with the instinct of Catholic tradition, which cherishes the legend that Lucifer’s revolt was directed at God’s eternal decree to take on flesh for the salvation of subangelic creatures. The devil revolts against the human nature so loved by God that He sent His only Son to dwell among us, to sing the Hebrew psalms and dance at the wedding feast.16 The devil has no feast because he is not humble enough to sit at the table as an invited guest, like the composer who sits humbly before the tonal scales and their primacy; he has no melody to sing because a melody, being determinate, binds its singer to a structure that does not depend on his will; he has no wedding to dance at, because a person who will not dance at a wedding should not come—I am speaking, of course, of a real dance, and of a guest with the talent to do it. Dancing demands laying aside one’s idiomatic steps to adopt the spirit and form of the dance.

Schoenberg, as we have seen, became convinced that the tonal system itself was to blame for the crisis of expression and had to be scrapped in favor of a “new music” that would have the democratic simplicity of letting every tone be free and equal—in his own phrase, the “emancipation of the dissonance.” At the premiere of his song cycle Das Buch der hängenden Gärten on January 15, 1910, Schoenberg announced that he was conscious of “having broken through all boundaries of a by-gone aesthetic.” In championing such a project, he was thoroughly a child of that fin de siècle Vienna which produced the motto emblazoned on the futuristic Sezession hall: “To each age, its art; to art, its freedom.”17 Absolute freedom in music and absolute equality of tones is, however, as destructive as absolute freedom in politics and absolute individualism, and for much the same reason.

Visual parallels

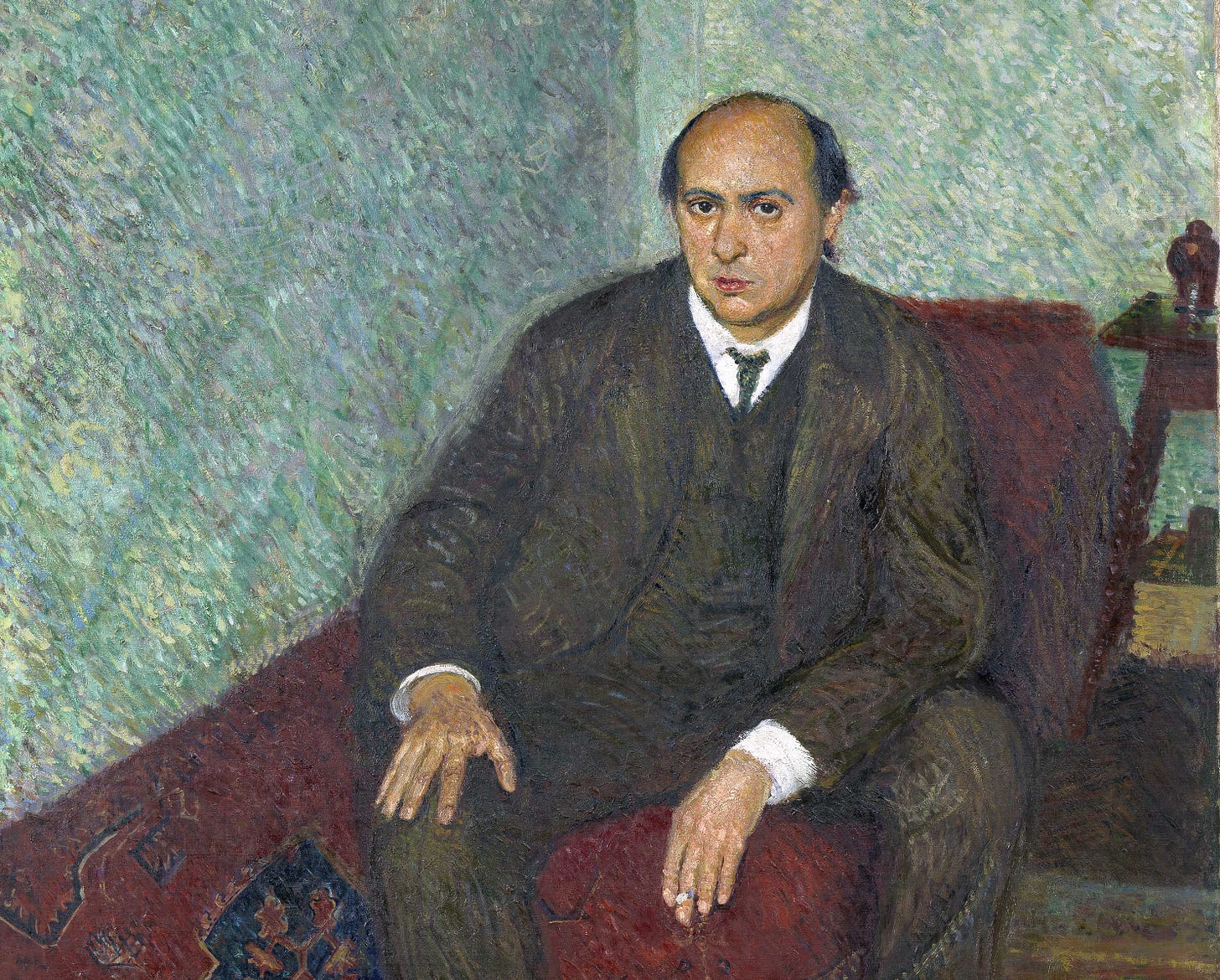

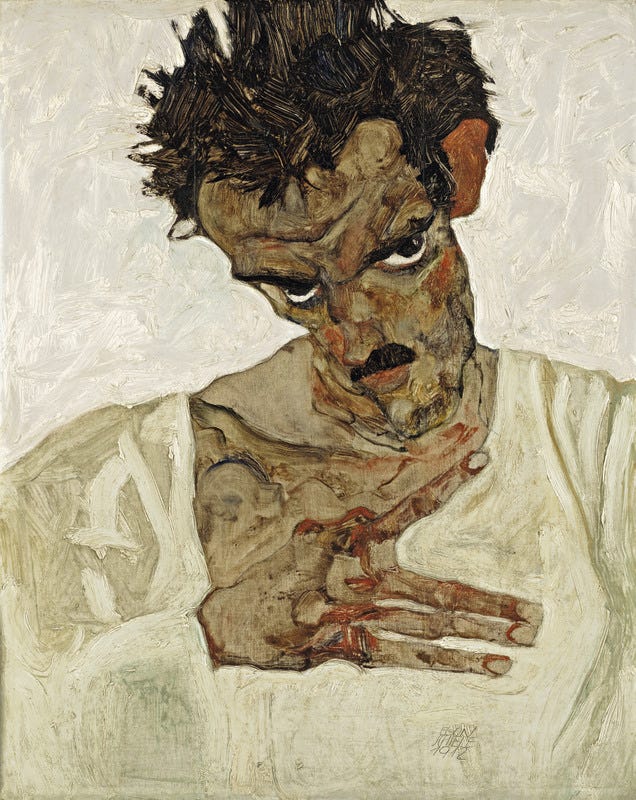

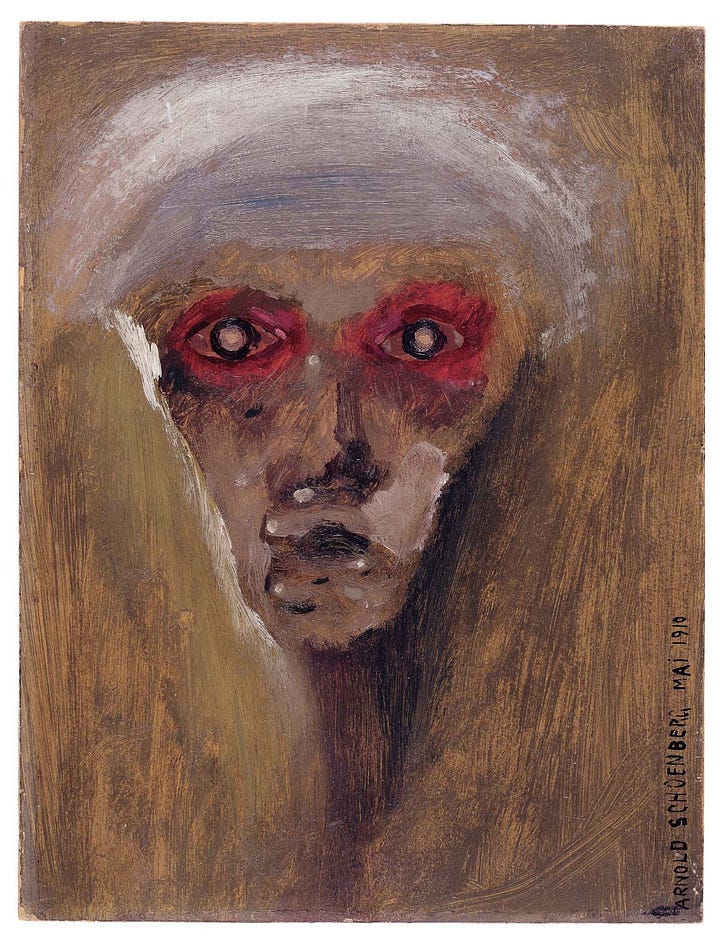

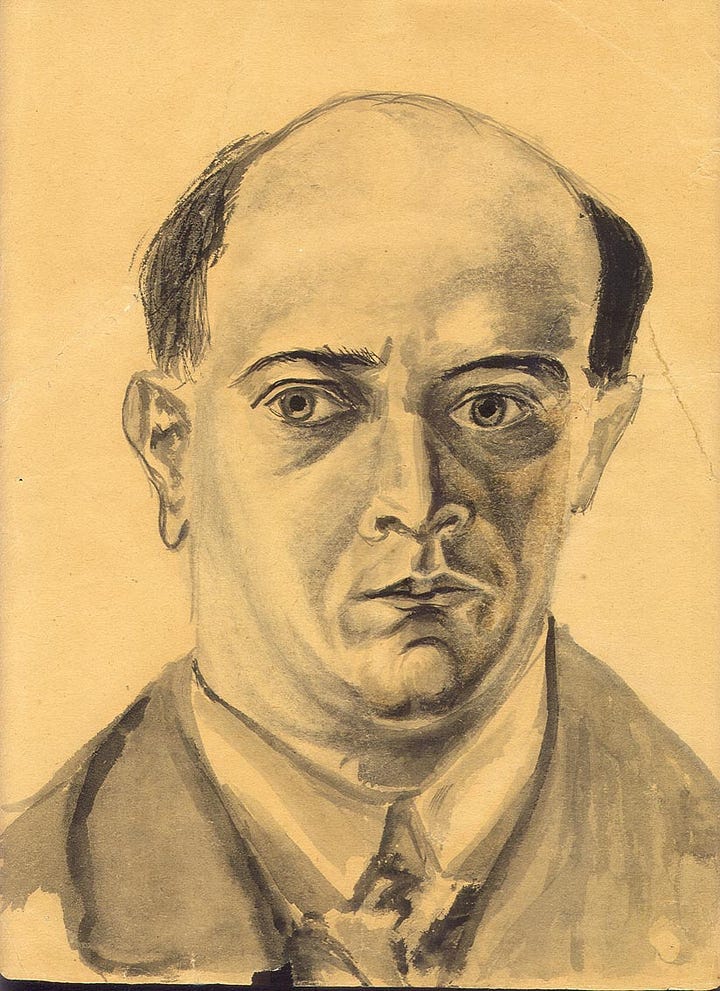

At this time, Schoenberg’s friend Kandinsky, who began his career as a painter with an impressionistic style not far from Pissarro’s or Monet’s, unveiled his first experiments with abstractionism, the dismantling of natural forms and their arbitrary geometrical reconfiguration. Schoenberg’s friends and contemporaries Klimt, Kokoschka, and Schiele also had painterly gifts, but each followed the winding path of subjectivism—Klimt, the most talented, in the direction of looser form and a preoccupation with eroticism, Schiele in the direction of misanthropy and sexual obsessions that can make his work nauseating to behold, Kokoschka in the direction of spatially dislocated fantasy.

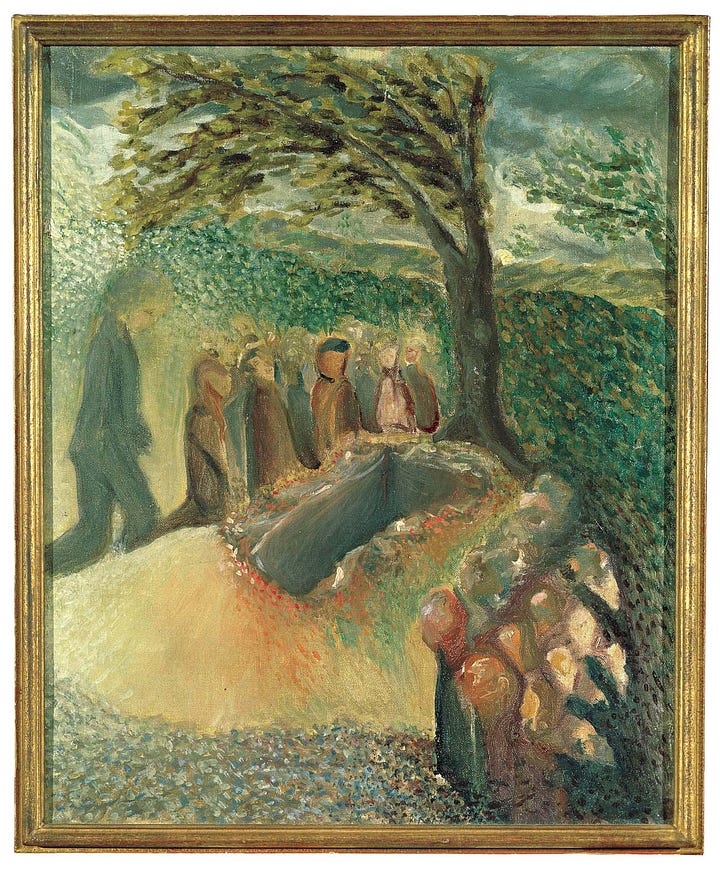

In his spare time Schoenberg himself tried his hand at visual art, producing Edvard Munch-like portraits and ethereal landscapes that might well serve as visualizations of the early atonal works.

In these artists and their work, one can see the imprint of multiple dualisms: woman against man, individual against society, convention against nature, tradition against freedom, and at bottom, spirit, mind, will, against flesh, bodiliness, incarnation. Like the contemporaneous revolutions in painting and architecture, Schoenberg’s revolution in music was a new brand of Cartesian intellectualism built upon a dualistic anthropology.

Disembodied Cartesian consciousness

An admiring music historian hears in Schoenberg’s Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19 (1911) “the urge to total introversion”; the composer seems “intent on attaining a chill abstraction” and the music, in most instances, “takes on a chill, severe” aspect.18 The first piece “avoid[s] any unifying elements”; in another, we hear “the stubborn but irregular repetition of a major third, which fragments of melody interrupt only to be sucked back into the trance-like reiteration”; in the final piece of the set, “motionless planes of sound set against one another create a chill, insubstantial timbre which hovers on the edge of silence.”

The music of the second of the Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23 (1920–23) “erupts in violent gestures” and closes with a dodecaphonic waltz, an undanceable dance. (I should define dodecaphonic: it is a coined term that refers to the new law Schoenberg handed down after a certain point, namely, that a “series” or “row” should be devised that utilizes all twelve chromatic pitches of the Western scale, and that this row should then be taken, in its various permutations, as the basis of all the musical development. This is no longer free atonality but regimented twelve-tone composition.)

Regarding the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 (1921–23), with its traditionally-rhythmed yet atonal movements, the critic accurately observes: “The effect is to produce a disturbing sense of alienation, since these 18th century forms produce tonal expectations which the music systematically denies.” What are these tonal expectations? One could give textbook definitions, but finally they are something one feels in the gut, one knows to be right.19

Atonal music, particularly after Schoenberg’s unveiling of the twelve-tone system in 1923, is the work of disembodied Cartesian consciousness. To the satisfaction of it adherents, here at last is music born of that “pure reason” over which man enjoys apparent sovereignty.20 In reality, it is music of alienation, of separation from oneself, the supreme artistic testament to uncompromising spiritualism. It is disturbing because it is disincarnate, frozen, at cross purposes to the fires of life, the embers of affection. It shares the ateleological immateriality and immobility of mathematics. Once again, we cannot fail to be reminded of Descartes’s resolution to banish from natural philosophy all traces of formal and final causality, leaving only raw matter and mechanical agency. But good music is as teleological, as dependent on form and goal, as nature herself, whereas bad music is like Aristotle’s “misbegotten monsters” which at times occur when something goes wrong in the process of generation.

In 1917, Schoenberg began to write an oratorio on the subject of Jacob’s ladder—Die Jakobsleiter, characterized by its author as “the union of sober, skeptical awareness of reality with faith.”21 He could not complete it; much of the project remained in sketch form. This might be viewed as poetic justice. One can climb up to heaven on a Jacob’s ladder of beauty; there is no ladder of ugliness, or if there is, it leads downward. Schoenberg later attempted another large-scale religious work, the opera Moses und Aron (1930–32).

Here is the musical depiction of the golden calf, which I actually find quite compelling in its brutality:

Once again, he could not bring this work to completion; Act III was left a fragment at the time of his death. The opera’s doom was sealed (claimed the composer) by the impossibility of working around “some almost incomprehensible contradictions in the Bible.”22 Spoken like a true higher critic!

Perhaps the difficulty stemmed rather from the aesthetic problem he inaugurated, which the opera’s anti-lyricism and fragmentary fate symbolize with eerie accuracy. Moses is afraid to undertake the divine commission because he cannot speak well. By the providence of God, he finds in Aaron a man who can be his interpreter. Faced with a crisis of communication, Schoenberg, unlike Moses, finds no one who can understand the music he feels commanded to produce,23 for it is no longer a language fraught with intrinsic meaning, but the clash and clang of bare notes, like a group of letters thrown together at random.

Music without hope

“Everything I have written has a certain inward similarity to myself,” he once remarked.24 As a baffled believer, the Schoenberg of Die Jakobsleiter and Moses und Aron was trying to express his faith in a transcendent God—yet by means of music incapable of expressing anything but incoherence and confusion, despairing of the “ancient beauty ever new.” When music abuses the inner nature of its forms and materials, it can only unsettle and disquiet the soul of the listener. Such feelings do not betoken good art; they rather signify psychological disorder, the flight from truth. In fact, they may signify above all the stance of despair, as a musician-critic opines:

It is entirely possible that Schoenberg invented atonal music because it is music that gets rid of all “hope”, whereas tonal music, no matter how somber, by its very nature always has “hope” (the consolation of tonality). Atonal music is music without consolation, and thus exactly expresses the hopelessness and despair that so many people felt in the 20th century. No other music does this.25

Atonality is the music of a nightmare world where no loving Father shares His joy, no Savior shows the way, no Spirit seals the promise—a world without certainty of truth, promise of life, hope of resurrection. Tonality is the musical analogue to eternal law, the origin of all reason and revelation. In the words of the great conductor Furtwängler: “For all its excitement (which can be carried to the limits of human understanding) every masterpiece of tonal music radiates a profound, unshakeable, penetrating peace.”26 Atonality, then, would be the musical analogue to chaos, night, the absence of God, the nihil.

A contemporary composer from England, Frederick Stocken, observes:

It always amazes me how such disparate musical styles as baroque, classic, and romantic (in fact all music from Josquin to Bruckner) have far more that unite them than separated them. In this period of some five hundred years, in a period in which music retained faith in its musical laws, the supremacy of the so-called musical triad (otherwise known as the common chord) remained involved, the key system was expanded though never changed, and the hierarchy of chordal relationships within keys remained constant. In terms of basic musical structures, the form and chordal procedure of a Josquin motet work in a surprisingly similar way as [those] in a Bruckner symphony [do]. True—and astonishing.

But what happened when music entered the twentieth century? Those laws…were rejected. Is it mere coincidence that in the very year, 1907, that Schoenberg began ripping the intestines out of music in his first atonal compositions, Pope St. Pius X was issuing his encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis, against Modernism? To the casual historical observer the activities of an atonal composer and a Pope shoring up the theological purity of the Catholic Faith would seem entirely separate. But…it is only too easy to see that there may be a link, a spiritual causal relationship between the decline in Catholic, and indeed all Christian, belief in the West, and the collapse of music.27

In my opinion, the rise of twentieth-century popular music can be understood as, at least in part, the (more or less conscious) reaction of natural musical instincts against the icy intellectualism and emotional contraception of atonal modernism. Like most reactions, it veered too far in the opposite direction, that of the flesh unelevated by spirit. The pulsating rhythms, limited repetitious chords, and simplistic melodies were well suited to sensual stupefaction, a musical “intoxication” analogous to states produced by drugs or alcohol. Jazz, rock, and their various offshoots fed the carnal appetites of an increasingly materialistic and hedonistic West in a feedback loop.

I cannot go further into this topic here, but suffice it to say that atonality as ushered in primarily by Schoenberg not only caused the near-death of art music but also prompted the carnalization of popular music. Here is an artist-revolutionary who, like other revolutionaries in history, has much to answer for.

Tonality is the musical equivalent of the gift of being: it is there, in reality, before we awaken to it, without our choosing it, and it imposes a “natural law” upon us — the law of receiving the gift with gratitude, letting it germinate and fructify in the heart, and then casting its seeds into the world, to reproduce there the image of the love that was first and is always given.

Tonality is thus, for those whose ears are attuned to its message, a symbol of all that is given in the bodily creation and its resplendent recreation in Christ, the Word made flesh, soundless light made audible and opaque. Within this orderly cosmos of the gift is limitless room for the exercise of a grateful freedom. Within the gift of hierarchical harmony is a gentle but insistent invitation to make music that will last, even in the memory of the new heavens and the new earth.

It is only in the ultimate vision of God, when, according to Hippolytus, the Logos is “the holy leader of the dance,” that man redeemed will join in the easy rhythms of truth and that, as we are told in the epitaph of Niketoras, we shall “dance with the choirs of the saints.”28

Let’s cleanse and refresh our ears with the glorious polyphony of “Libera nos, salva nos” by English composer John Sheppard, who lived c. 1515 to 1558, performed by the Gesualdo Six:

This post, with the voiceover, took DAYS to put together. Extra donations would be welcome to fund more cultural explorations at this level:

My friend Massimo Scapin also commemorated this anniversary, with an article over at OnePeterFive. I had written and scheduled mine one before seeing his.

Seventy years, quite apart from its biblical resonance, seems to be about the maximum length of time that a gross error can possess an entire society, before collapsing under its own weight. The Soviet Union furnishes one example.

For a brief biography of all three men, see Harold C. Schonberg, The Lives of the Great Composers, rev. ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), 595–612. Documentation on Schoenberg’s life and works is available from the Arnold Schoenberg Center in Vienna (www.schoenberg.at), from which I have drawn many details.

This sentence adapts the description given in The Grove Concise Dictionary of Music, ed. Stanley Sadie, rev. ed. (London: Macmillan, 1994), s.v. Wagner.

See “Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, The String Quartets: A Documentary Study,” accompanying the complete quartets on 4 CDs (Deutsche Grammophon 419 994-2), pp. 236–37.

See the chapter on Schoenberg in E. Michael Jones, Dionysos Rising: The Birth of Cultural Revolution out of the Spirit of Music (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1994), 99–137.

“Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten. / Mir blassen durch das dunkel die gesichter / Die freundlich eben noch sich zu mir drehten. / Und bäum und wege die ich liebte fahlen / Dass ich sie kaum mehr kenne”; “In einem meer kristallnen glanzes schwimme—/ Ich bin ein funke nur vom heiligen feuer / Ich bin ein dröhnen nur der heiligen stimme” (from a poem by Stefan George, with capitalization as in the original). See “The String Quartets: A Documentary Study,” 48–49.

See Summa theologiae I, q. 45, aa. 1, 2, and 5.

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), 191.

Donald Jay Grout, A History of Western Music (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973), 206.

Paolo Petazzi, notes to Schoenberg: The Piano Music, Deutsche Grammophon 423 249-2.

The Grove Concise Dictionary of Music, s.v. Schoenberg.

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1987), §6, p. 54; cf. §1, p. 44.

For all these points, see Critique of Judgment §1, p. 44; §58, p. 224; §5, p. 51; cf. §2, p. 46. I don’t think for a moment that Kant would personally have endorsed Schoenberg’s music; I believe he would have found it abhorrent in its departure from the “laws of nature” of which Enlightenment thinkers were so fond.

The attribution to Descartes appears to be no longer tenable; see Richard A. Watson, Descartes’s Ballet (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 2004).

For a beautiful meditation on dance as “sacral play” and metaphor of the spiritual life, see the chapter ‘The Heavenly Dance’ in Hugo Rahner, SJ, Man at Play, trans. Brian Battershaw and Edward Quinn (New York: Herder and Herder, 1967), 65–90.

For a vivid evocation of the period, see Carl Schorske, Fin-de-siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York: Vintage, 1981).

Petazzi, notes to Schoenberg: The Piano Music.

As the pagan philosophers had already realized through experiments with stringed instruments, there are laws of sound and of tonality that can be empirically discovered and mathematically formulated. These ancient insights into the objective nature of musical tones, melodies, and note combinations were refined and amplified by a long line of subsequent thinkers, including Augustine, Boethius, and the composer Rameau. More recently, the objective grounds for the subjective perception of rightness in music has been the focus of important, if little known, studies, such as Molly Gustin’s Tonality (New York: Philosophical Library, 1969) and two books by Victor Zuckerkandl, Sound and Symbol (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969) (see esp. 11–71) and The Sense of Music (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971) (see esp. 11–79).

Schoenberg’s atonal works to some extent emerge from and appeal to more than pure intellect, since music cannot exist except as sensibly perceived and experienced, and thus taken into the inner life of man where it is capable of eliciting a response of the whole person. A purely intellectual music would ipso facto be mathematics and nothing else. Nevertheless, atonal music is intelligible and communicative only to the extent that it is tonal, i.e., only so far as remnants, echoes, associations, expectations of tonality and regular rhythm are played upon. Indeed, in their cumulative effect on the listener, Schoenberg’s expressionist works (e.g., Erwartung, Die glückliche Hand, Pierrot lunaire) have a spiritual-sensual power comparable to that of traditional music—yet the effect produced in a sensitive listener is one of disorientation, dread, nausea. It is the sound of unsoundness, a musical representation of mental derangement.

Schoenberg had converted to Lutheranism in 1898, seemingly for cultural reasons, but returned to the practice of Judaism in 1933, upon his emigration from Berlin to the United States. At the time of his death in 1951, he left incomplete a set of religious poems, the last work to receive an opus number (50). The second in the set was Psalm 130, the ‘De profundis’, in Hebrew.

Quoted in H. Schonberg, Great Composers, 612.

This is no poetic turn of phrase; Schoenberg once wrote, speaking of his shift from tonality to atonality: “The Supreme Commander had ordered me on a higher road.” “I believe what I do and do only what I believe; and woe to anybody who lays hands on my faith.” “It is my historic duty to write what my destiny orders me to write” (Schonberg, Great Composers, 596, 602).

Quoted in ibid., 599. At the peak of the opera, Moses comes down the mountain and finds the people celebrating an erotic orgy, driven wild by human sacrifice and lust. Later, Moses exclaims: “I love my thought and live for it.” Jones comments: “Moses/Schoenberg’s deepest wish is not to proclaim the law of God, which in musical terms would have been analogous to the diatonic scale and, therefore, not ‘his’ idea. His deepest wish is rather to impose his ‘idea’ on reality in a purely arbitrary and violent way. . . . Schoenberg’s solution is to kill the dancing girls, kill harmony, reimpose the law, which is Moses/Schoenberg’s ‘thought’. Like Shylock, Schoenberg can say: ‘I crave the law.’ . . . It [this law] is not an attempt to discover an order in nature, because the experience of the past half-century had convinced the moderns that there was no order in nature. The only order in the universe is the one we impose” (Dionysos Rising, 134).

John Franklin, Thoughts and Visions (www.thoughtsandvisions.com/#thoughts), p. 50.

Cited in Derek Watson, Bruckner (New York: Schirmer, 1997), x.

Frederick Stocken, “The Christian Art of Music,” The Catholic Faith 6.4 (July/August 2000), 22.

H. Rahner, Man at Play, 66–67.

Not sure I can "like" this, nor can I listen to the music in case it gives me nightmares! I had to endure studying it many years ago and this, along with Shenkerian analysis, are the stuff of sleepless nights. But you make some good points here. For me, the atonal stuff of the 20th century embodies the spiritual desert of the modern world. Give me Gregorian chant any day.

I couldn't agree more. As a young composition student I never could quite understand what people saw in atonal (especially dodecaphonic) music. On the other hand, I have long wondered about the appeal of non-harmonic sounds, such as the overtones of bells, and especially the exquisite music of the Javanese gamelan, which I spent some years studying. Non only do most of the instruments, consisting of bronze gongs and slabs, produce non-harmonic overtones, each set of instruments (that is, each gamelan) has its own unique tuning. Tuning is an aesthetic variable. So here is a refined and sophisticated system of music in which you will rarely hear what we in the West call "consonance" and yet it is thoroughly human, full of soul, and, in my experience, is capable of providing access to something approximating the divine. I once had a recording playing when a roommate, a horn player, who had never heard Javanese music before, came in. His response: "It sounds like I've died and gone to heaven."