“The Catholics” (1973): A Trad Film Ahead of Its Time

A minor “cult classic,” this work evocatively dramatizes our present conflicts

A modernist Vatican in pursuit of ecumenism and worldly ideology, determined to stamp out the Latin Mass. The peremptory order to adopt a new Mass in English, facing the people, in the name of “obedience.” Faithful priests and laity resisting and drawing Rome’s ire. Wolves in sheep’s clothing.

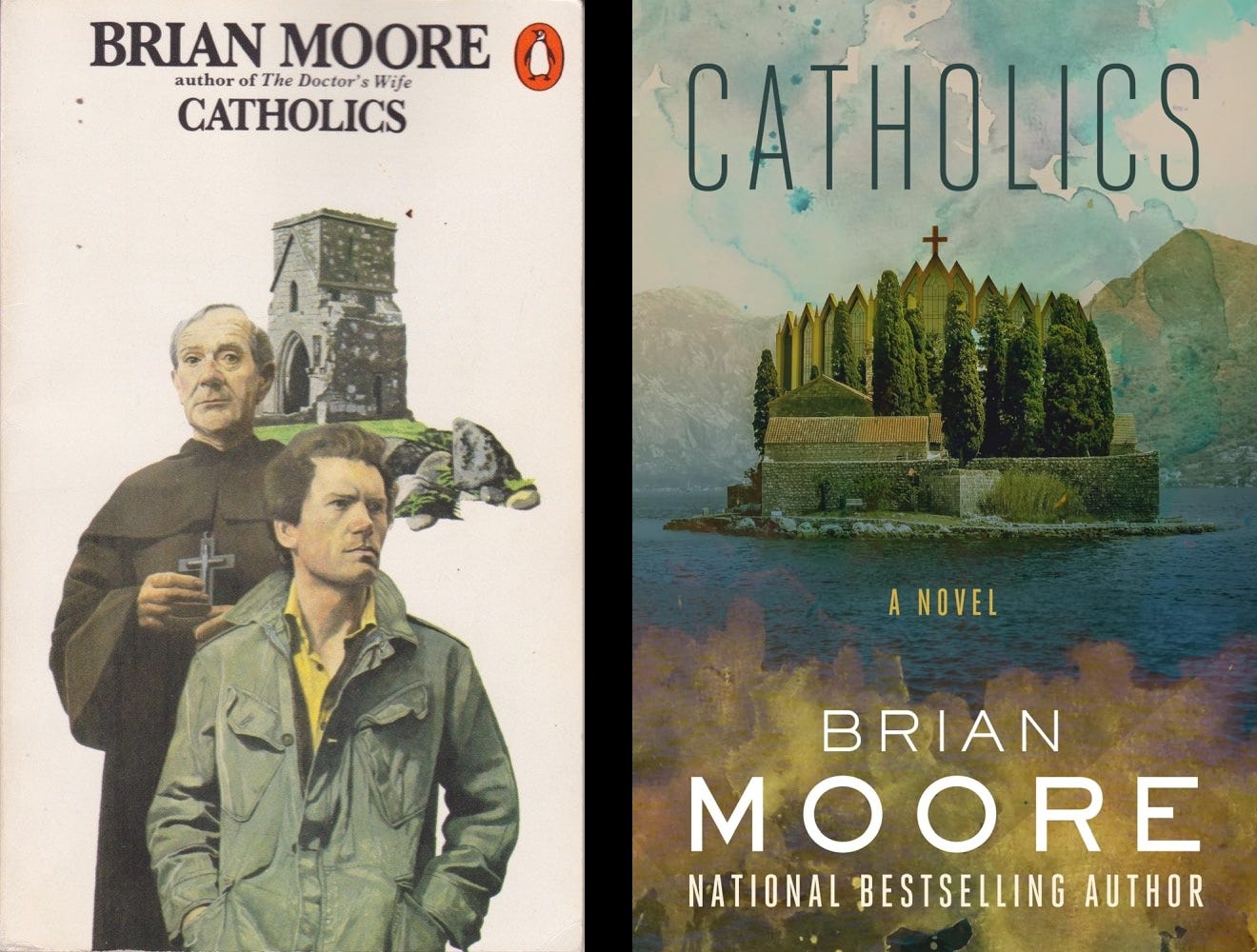

As similar as this may sound to the current situation in the Church, I am actually referring to the plot of the 1973 TV film The Catholics, directed by Jack Gold and starring Trevor Howard and Martin Sheen. Based on the novel Catholics written by Brian Moore a year earlier, the film (which is in the public domain and viewable in its entirety here) depicts the inevitable clash between Tradition and Modernism which has come to characterize the Church since the Second Vatican Council. While intended to be fictional, the storyline is eerily prophetic of today’s post-Traditionis Custodes landscape, which has so much in common with the post-Vatican II chaos familiar to the film’s first audiences.

Despite being laden with themes and imagery that will resonate deeply in every tradition-loving heart, The Catholics has elicited astonishingly little commentary amongst traditionalists to date. With this movie review, I hope to encourage a wider rediscovery of this film and a deeper reflection upon the motifs it explores, now even more relevant fifty years later.

The story centers upon a fictitious group of monks from an island monastery off the coast of Ireland who have drawn international attention by continuing to celebrate the old Latin Mass in defiance of a futuristic Vatican that, even by today’s standards, has gone far off the rails. At the time in which the film is set, Vatican IV (!) has occurred, individual Confession is now banned, priests don’t wear clericals but do espouse Liberation Theology, the Mass is declared to be only symbolic, and a Catholic-Buddhist rapprochement is imminent. (Some of this, sadly, doesn’t sound far-fetched today; the film’s producers clearly intended to depict a mainstream Church that had only continued in the progressivist direction of Vatican II itself.) Meanwhile, the tradition-retaining monks have been journeying to the Irish mainland to continue ministering to Catholics according to the “old ways,” soon drawing devotees and pilgrimages from all over the world—and fueling Vatican fears of a “Counter-Revolution” that could jeopardize the ecumenical progress of the new “revolutionary” Church.

The film’s opening scene will no doubt give every traditionalist goosebumps. A “forbidden” Latin Mass is being celebrated on the cliffs of the Irish coastline, harking back to the long history of persecution of Catholics in that country. Flanked by two acolytes, an elderly priest approaches a stone altar akin to the “Mass rocks” of Penal Times and intones the timeless words of Psalm 42: “Introibo ad altare Dei.” Behind him kneels a throng of pious souls, assisting at the Low Mass with great devotion. As the camera pans throughout the crowd, we see worshippers from every background and age; some carry signs that say, in various languages, “Bring Back Latin Mass” and “We Want Our Mass in Latin.” It is as if, even in 1973, less than a decade after the widespread introduction of the vernacular, the film’s producers anticipated the worldwide appeal of the timeless Roman Rite—and the various popular demonstrations that would be held in its defense.

Only one figure is not kneeling. Standing and watching the Mass from a distance is a man we will later come to know as the modernist priest, Fr. James Kinsella (Sheen), sent by the Vatican to suppress the monks’ traditional ways. A widely deleted scene, preserved in the video linked above, shows Kinsella receiving his marching orders from the monks’ own Father General in Rome. The conversation between them likely does not differ much from what one might overhear in the Vatican halls today:

Father General. So you have some idea of what’s in store for you. Fanatic monks. What sort of dialogue can one possibly have with men like that?

Kinsella. Well, we do have some things in common, sir.

Father General. What, for instance?

Kinsella. Well, we’re priests. And we’re all members of the same monastic order.

Father General. I wonder, does this Abbot believe that?

Kinsella. What do you mean, sir?

Father General. I mean that the Church today is like the early Christian Church—revolutionary! And this Abbot belongs to the Church we have left behind.

Landing by helicopter on the island where the monks live, Kinsella soon meets the Father Abbot (Howard), who politely and diplomatically welcomes him to the monastery. Clearly aware of the reason for his visit, the other monks attempt a more confrontational approach. In a heartfelt monologue that could have originated at OnePeterFive or Rorate Caeli, the simple and sincere Father Manus explains to Kinsella his attachment to the ancient rite:

You see, God sent His son on this earth and he died for us. He died for our sins. And that’s what the Mass is all about, you see. I mean, it’s just that—a commemoration of His death. And it was always in Latin. Because Latin is the language of the Church, and the Church is universal. I mean, a fellow could drop into a church anywhere in the world, anywhere, and hear the very same Mass—the Latin Mass, the only Mass there ever was—and the fact that it was in Latin, well, that was part of the mystery. Because you weren’t just talking to your neighbor, you were talking to Almighty God, you see. Anyway, that’s the way we’ve been doing it for the past 2,000 years… Oh, it’s a mystery, of course it’s a mystery.

No doubt, the traditionalist viewer will find it hard to refrain from cheering in the background (even if he might offer a slight precision and say “for the past 1,700 years”). Yet in the movie, the modernist Kinsella says nothing in reply. Even the Father Abbot, looking embarrassed at this unfiltered candor, says, a bit mysteriously, “I wish I had all that conviction.”

Kinsella is later confronted in the dining hall by the even more outspoken master of novices, Fr. Matthew, and by Fr. Kevin, who has helped organize an all-night prayer vigil “for the preservation of the Mass.” In an unforgettable conversation, the latter clashes with Kinsella on the very nature of the priesthood:

Fr. Kevin. Do priests from Rome not dress like priests anymore?

Kinsella. No, only on special occasions.

Fr. Kevin. You’re one of those “new priests,” aren’t you? The revolutionaries.

Kinsella. Are you interested in that?

Fr. Kevin. Tell me, is it true, in South America some priests are overthrowing the government?

Kinsella. Yes, they are.

Fr. Kevin. How can they be doing the likes of that?

Kinsella. Why not? The early Christians were revolutionaries, remember?

Fr. Kevin. What has that got to do with saving souls for God?

In the same dialogue we hear an exchange that will resonate with all families who have searched (sometimes for years) to find authentic Catholic worship:

Fr. Kevin. Look at the people over there on the mainland. They don’t want your social justice. They want the old Mass. They want to believe in something. Something more than this world can offer them. What do you offer, Father?

Kinsella. Well, perhaps a better life, Father! Not pie in the sky.

Fr. Kevin. But you’re a priest. That’s not your job. They want you to forgive them their sins. To baptize them, marry them, bury them, show them there’s a God above them, a God who cares about them. The old parish priests knew that. You don’t.

Despite the modernist drift of the “new clergy” represented by Kinsella, despite the emasculation of the priesthood and the evisceration of Christian dogma, there is one traditional concept that even the post-Vatican-IV Church depicted in The Catholics has retained—that of obedience! Not unlike what we see in our own days, the word “obedience” is constantly used as a weapon by those in authority, creating for the monks a genuine crisis of conscience between fulfilling their third vow and doing what they know is right. And while the new ecumenical Church no longer wishes to define heresy, Kinsella remains absolutely firm—one might even say “rigid”—on the necessity of unconditional obedience to superiors. Quipping that “yesterday’s orthodoxy is today’s heresy,” the Father Abbot pushes back:

Father Abbot. Did you know Ireland was the only country in the world where, once upon a time, every Catholic went to Mass on Sunday? Every one, even the men…

Kinsella. That’s impressive.

Father Abbot. …until the time of Pope John [sic], when the new Mass came in. Well, we were like everybody else. We obeyed orders, went over to the mainland, said the new Mass in English. And the people stopped coming to church. Oh, some women [came]. But the men and the boys stood outside smoking. So I was worried, I said to the monks: What on earth are we doing if we cannot persuade the people to come back into the church? It’s the priests’ job to keep their faith in Almighty God and I don’t want to tamper with their faith, so I decided: we go back to say the old Mass in the old way! And, well, that’s the whole story.

Yet, as we learn, this is not the whole story. The Father Abbot, too, is not afraid to wield the sword of “obedience” to justify the raw exercise of his authority over the other monks. Discovering the all-night prayer vigil, he orders the monks back to bed and—in an accusation that will sound all too familiar to traditionalist ears—harshly admonishes Fr. Matthew for his “insolence and insubordination.”

As is so often the case in real life, the monks’ fate lies in the hands of their superiors. There on the fictional island monastery, as today in our communities, competing ecclesiologies clash because they are ultimately irreconcilable. In the film’s closing scenes, a crisis of faith stuns even the modernist Kinsella. I suspect this crisis will be less of a shock to the traditionalist viewer who has, unfortunately, seen the same script play out time and time again in reality.

To me, the ending is unsatisfactory. I will not spoil it by giving too much detail, but suffice it to say that it seems to me that the storyteller, seeking a resolution to the story, found it in a submission or surrender that returns to spiritual “basics”—as if it would be found in a kernel of “mere Christianity” beneath all the debates. In reality, what is needed is that the island monks would send the modernist heretic packing while they remain faithful to their way of life until the storm passes. What would be needed is something like a Tolstoyan novel of multiple generations showing how a resistance like that pays off in the end. This is perhaps far too much to ask of a TV film, or a novella, for that matter!

Other viewers find the ending deliberately ambiguous and ambivalent, in keeping with the confusion of the period in which it was made.

In any case, the film offers lessons for real-world traditionalist resistance to abuses of authority and reminds us that preserving the Catholic Faith intact is our primary obligation, prior to any obligation we may have to singular church authorities.

In terms of a real-world comparison, my friend Alex Begin wrote a brief column pointing out several striking parallels between the monks of The Catholics and the Sons of the Most Holy Redeemer (a.k.a. Transalpine Redemptorists) founded in 1988, fifteen years after the movie was made. These Redemptorists are living on a remote island, in fidelity to a centuries-old rule of life. They offer exclusively the traditional Mass. They bring this Mass (and all that goes with it) to scattered communities of the faithful. The scenario of the film is surpassed by the reality of this community animated by the traditional Catholic Faith.

There is so much more that could be said about this film The Catholics. Yet it seems best to bring this article to a close and encourage readers to watch it for themselves and form their own opinions. I would be genuinely delighted to hear your reactions in the comments here. Watch, ponder, and discuss this prophetic 1973 film, which anticipated the situation we ourselves now face in our own fight to preserve the liturgical and spiritual riches of Holy Mother Church.

As things has been developing in the hierarchy, the more I am convinced that the “towards the people” mass is initial metaphorical step of the hierarchy’s attitude towards God.

Seen from the context of the sanctuary where the Holy Eucharist was at the centre, it does appear the turning of the hierarchy’s back towards God to make the people the priority.

The mass has become about the people. This is in contradiction to what Jesus did. The sacrifice was first and foremost about God not about people.

Yes, secondarily. It was about people Jesus offered himself to appease the wrath of God against humanity. The mass was to God, although the mass is of the people in the person of Christ.

The problem with this modernist mass is has inverted the hierarchy of priority. Thus. emptying the meaning for the people. It becomes for the people, of the people and by the people. God has been excluded in the celebration of Son’s sacrifice.

For me, this is how it boils down to.

I remember this film from years ago and it still resonates. My recollection is that in the end, obedience supplanted faith - it is all that can last. Prescient too, the progressive church of today is also enforcing obedience in place of faith.