The Heady Sport of Violating the Principle of Non-Contradiction

Though popular across the whole terrain of modernity, it found its most dedicated players in the liturgical reform

“Who will stop me?”

Ever since Hegel, the death-defying sport of openly violating the principle of non-contradiction—namely, that a thing cannot both be and not be at the same time and in the same respect—has grown in popularity. Hegel, for his part, postulated a historic-logico-metaphysical process by which the clash between thesis and antithesis would inevitably yield a higher synthesis. Nowadays, however, people seem quite content to grab the thesis and the antithesis and sit down cozily with both of them, making no attempt at synthesis; indeed, one wonders if they even notice the conflict.

In his masterpiece On the Primacy of the Common Good, the eminent Canadian Thomist Charles De Koninck noted that contradiction is unthinkable but not unspeakable: one cannot truly think that I am both here in this place and not here in this place at the same moment, but I can say ”I am here in this place and not here in this place at this moment.” That, in fact, is the definition of nonsense, literally, lack of sense, since what has been signified is impossible either in the order of being or in the order of thought; the words correspond to nothing in reality. Here is the exact passage from De Koninck:

One can say and write things that one cannot think. One can say, “It is possible to be and not to be at the same time and in the same respect”; “the part is greater than the whole,” though one cannot think such things. But yet, they are grammatically correct phrases. Transcendent power of language: one can say both the thinkable and the unthinkable. . . . I can say: “I do not exist.” And with that, I can found “I exist” on pure non-being. I say it! Who will stop me?1

We see this kind of thing all the time nowadays: a man saying “I am married to a man” or “I am a woman.”2 I’m sure readers can think of their own favorite examples of a sheer contradiction in words that has no corresponding thought, let alone reality, behind it—where the human power to speak inanity, a sign of our extreme debility in the metaphysical scale (no angel, let alone God, could be so feeble), is foolishly believed to be a power that dominates and shapes the world unto itself. What really happens, as we see all around us, is the cortège macabre of lives broken by self-sabotage, hearts polluted with the trash of rotten desires, souls screaming to their dumb idols for deliverance.

Now, it so happens there is one arena in which this sport has become particularly refined: the arena of liturgical reform. Here, it seems, contradictions abound like uncollected garbage on the streets of Rome. If they were gleefully asserted as such, they might make for a kingly entertainment, but since they are rarely said outright, the comic element is sadly lacking. Let’s look at a few today.

Respect for antiquity

The new rite preserves all the elements of the Roman Rite by abolishing lots of them and making most of the others optional.

The new rite preserves the authentic prayers of the preceding Roman Rite by keeping only 13% of them intact.

The liturgical reform successfully recovered lost elements from antiquity by removing many ancient elements, redacting every text it took from historical sources, and mixing in purely modern material.

Ancient elements are honored and preserved by being stripped away, revised according to modern cultural or moral sensibilities, and fused with texts and ceremonies created out of whole cloth.

The reform brought back the oldest Eucharistic anaphora in Rome, that of Hippolytus, by introducing into the missal a text that was never actually used as an anaphora, was not actually written by Hippolytus, and almost certainly did not come from Rome.3

Looking backwards is a sin—except for when members of the Consilium are looking backwards to a (fictitious) past of the Roman liturgy and pretending to restore ancient customs.

Fidelity to the Council

Latin is “preserved in the Roman rite” as John XXIII solemnly demanded in Veterum Sapientia (1962) and as the Council Fathers ordered (SC 36.1) by being declared an impediment to modern man and vanishing nearly completely from the Church of the so-called “Latin rite.”

The Council’s instruction that “steps should be taken so that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them” (SC 54) is best implemented by dropping all education in Latin, giving the people awful music that few of them ever want to sing, and ensuring they remain so ignorant that the phrase “Ordinary of the Mass” would mean next to nothing.

Gregorian chant is given “chief place in liturgical ceremonies” (SC 116) by being surrendered as anti-apostolic and disappearing from 99% of Catholic liturgies.

The reform perfectly fulfilled the Second Vatican Council’s desiderata by flagrantly contradicting some of them and grossly exaggerating others. The Spirit showed forth the vitality of this august synod by dumping the wishes expressed by the vast majority of the Council Fathers into the rubbish bin.

Holy Mother Church, “in faithful obedience to tradition…holds all lawfully acknowledged rites to be of equal right and dignity [and] wishes to preserve them in the future and to foster them in every way” (SC 4); this she does most effectively by unfaithfully disobeying tradition, holding rites approved and received for centuries to be of inferior dignity and giving them second-class legal status, and wishing to cancel them in every way that the Roman authorities can think of.

Active participation

The new rite fosters more active participation by removing substantial portions of the liturgy in which to participate and by abolishing many of the customs that reminded clergy and faithful alike of the meaning of what they are doing (frequent signs of the cross, bows, genuflections, etc.).

The new rite emphasizes the Sign of the Cross by significantly reducing the number of times it is used, both by the priest and by the people.

The liturgical reform led the way to a much greater participation of Catholics in the Mass because a much smaller percentage of the baptized come to Mass, and the majority of those who do come don’t believe that what makes the Mass the Mass—namely, transubstantiation—actually happens.

The new rite intensifies faith in the risen Christ and His presence among us because many who attend no longer believe in the Real Presence owing to the way the Eucharist is treated and handled.

The dignity of baptism, confirmation, and marriage is more emphasized by moving their conferral from the place of priority and honor it had enjoyed at the start of the service to a place sandwiched between the homily and the offertory.

Calendar & Scripture

The Catholic Church shows its relationship with and inheritance from our older Jewish brethren by obliterating the profound influences of the Hebrew calendar on the Mass, such as the four sets of Ember Days that hark back to the four periods of Jewish fasting, the links between Shavuot and the traditional Pentecost propers, and the long sequence of (pre-55) readings at the Easter Vigil that go back to the earliest centuries; and, moreover, we show our esteem for the people into whom Christ entered by canceling out the strong textual, gestural, and architectural links between Temple worship and the Eucharistic sacrifice.

The new rite gives greater prominence to the Temporal cycle than the old rite does by allowing parts of it—such as the season of Epiphany, the season of Septuagesima, Passiontide, and the season after Pentecost—to disappear that were never allowed to disappear in the old rite.

The new rite emphasizes seasonal periods of prayer and penance by eliminating Ember and Rogation days and omitting the pre-Lenten season of thinking ahead to Lent. By not preparing for a penitential season, we are actually more prepared. By not doing penances, we are actually more penitential.

The new rite emphasizes the importance of Lent by almost totally eliminating obligatory fasting and nearly all references to fasting. By reducing required fasting and abstinence to a bare minimum, today’s Catholics will be inspired to do even more penance on their own.

The new rite shares a richer banquet of the Word by excluding readings that had been used by the Roman Church for over a millennium and silently suppressing difficult verses of Scripture as well as entire psalms.

The new rite better familiarizes Catholics with the Word of God by so multiplying readings and avoiding repetition that almost no one can remember anything after two or three years.

By removing from the Order of Mass the verses recited from Psalms 17, 25, 42, 50, 84, 101, 115, 123, and 140 as well as the Prologue of St. John’s Gospel, the faithful will better acquire the spirit of Scripture and understand how the Mass is the realization of what it teaches us.

Ecumenism

The Western Church more strongly emphasizes its historical connection to the Eastern Churches by removing nearly every element they had in common—e.g., a one-year lectionary, ad orientem stance, barriers between the sanctuary and the nave, many days of fasting and abstinence, a calendar overflowing with saints, communion directly into the mouth—and by artificially importing into its liturgy Eastern practices that had never existed in the West (e.g., the consecratory epiklesis).

The Western Church aligned itself more closely with Byzantine practice by abolishing the subdiaconate (which Byzantines still have), introducing female ministers (which they officially do not have), and making the use of chant optional and, in practice, nonexistent (when officially all Byzantine liturgies are only chanted).

The Roman rite becomes more itself by divesting itself of what is most distinctively Roman and adopting a medley of Eastern elements—appropriately stripped of their sharp edges and combined with sheer novelties.

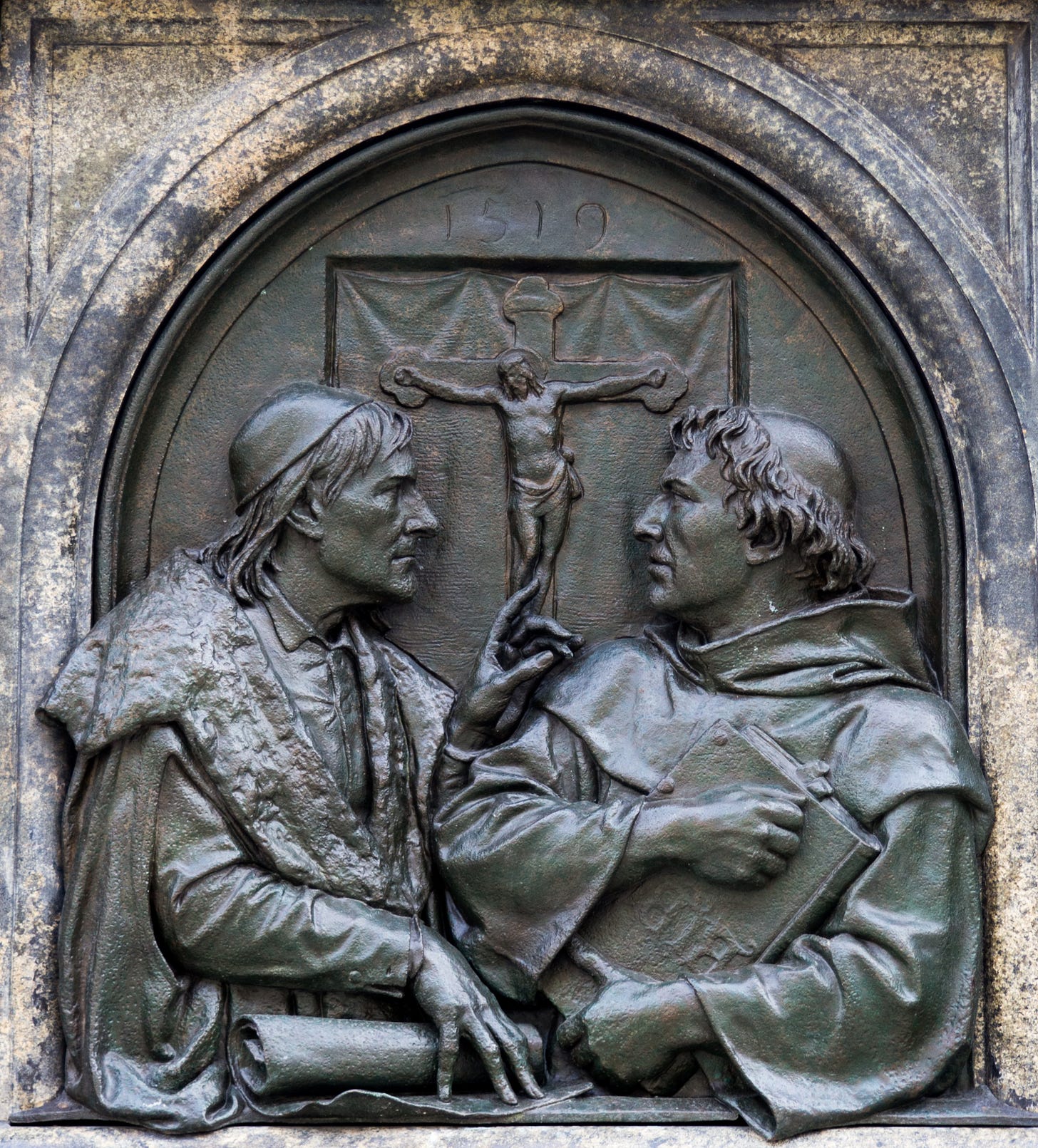

John XXIII’s description of the purpose of the Second Vatican Council in his opening address—that “the whole of Christian doctrine, with no part of it lost, be received in our times by all with a new fervor, in serenity and peace, in that traditional and precise conceptuality and expression which is especially displayed in the acts of the Councils of Trent and Vatican I”—is best fulfilled in liturgy by downplaying the dogmas most emphasized by Trent and adopting ideas and practices characteristic of Protestantism and Jansenism.

The new rite is more Trinitarian because it refers to the Trinity far less often than the old rite does.

The Mass is better understood by everyone as the sacrifice of the Mystical Body, Head and Members, due to the removal of language and actions indicating that the Mass is a true and proper sacrifice.

Envoi

These sorts of statements can be multiplied almost endlessly, once one begins to compare closely the old and new rites of anything—the Holy Mass, the other six sacraments, the Divine Office, the sacramentals, the pontifical ceremonies…

To the aforementioned splendid exhibitions of intellectual debility may be added a host of new contradictions ushered in by Pope Francis and his court, who are bent on outdoing earlier practitioners of the Hegelian sport. We are indebted to Gregory DiPippo for highlighting its truly Olympian dimensions: see “New Liturgical Anathemas for the Post-Conciliar Rite,” also included as an Epilogue in Illusions of Reform.

After a while, one cannot help wondering if partisans of the postconciliar reform have abandoned not only respect for tradition, but even classical logic and metaphysics. Has ideology addled their brains? I suppose there is a far worse possibility—one recalls Cardinal Stickler’s admission to Dom Alcuin Reid that Bugnini was not a Freemason, “but something far worse,” left agonizingly unspecified4—but rather than “going there,” I will lower a veil of dissembling silence.

Readers who would like to join in the game may share their favorite violations of the principle of non-contradiction in the comments!

The Aquinas Review 4 (1997), 86–87.

For reasons I explain in detail in this book, the habit of churchmen of saying “X is the Roman Rite” when X is very definitely and obviously not the Roman Rite is the liturgical analogy to the nominalism and voluntarism we see playing out in the LGBTQ+ movement. “Everything is connected,” as Pope Francis rightly observes; one merely needs to see where the analogies are.

See the Foreword to Yves Chiron’s biography of Bugnini.

Let us make the Church more Catholic by jettisoning all that is truly Catholic and make it Protestant.

Like many of the saints of old, thanks be to God for those rigid in their faith