The Leonine Prayers after Mass (Part 1)

For a better understanding of a small but powerful devotional treasure

Today begins a three-part series about the beloved prayers we recite after Low Mass.

How the prayers originated

For a period of about eighty years (1885–1964), it was customary for Catholics throughout the world to recite a set of prayers at the end of low Mass, in company with the priest kneeling at the steps of the altar. Sometimes referred to simply as “the prayers after Mass,” they are more usually called “the Leonine Prayers,” since it was the great Pope Leo XIII who, towards the end of the nineteenth century, gave them their nearly-final form.

During the whole period when they were in universal use, they were prescribed only for low Masses of a private or non-solemn character, when no further devotion followed after the Last Gospel. This means that any time Mass was sung (whether a Missa cantata with a priest or a Solemn High Mass with priest, deacon, and subdeacon), these prayers were omitted, as they were, too, whenever Mass was followed by Eucharistic adoration, public recitation of the Rosary, or any other such devotion.1

The original instigator of collective prayer after Low Mass had been Pope Pius IX who, in 1859, asked Catholics in the Papal States to recite three Ave Marias, the Salve Regina, and four collects from the Roman Missal. In 1884, Leo XIII replaced these four Collects with a single Collect, then in 1886 substituted a new Collect and added the St. Michael Prayer, this time extending the recitation of the prayers to the entire Church around the world, for reasons I will go into later (in part 3). The threefold invocation of the Sacred Heart was added by St. Pius X in 1904, and with that addition, the set was complete.2

The rage for simplification

The decree Inter Oecumenici of September 26, 1964, which implemented a first raft of liturgical changes even while the Second Vatican Council was in progress, stated bluntly: “The Leonine Prayers are suppressed.” No explanation given, but it’s highly likely that an abbreviating chop-chop mentality was at work: the shorter, the better (except for the lectionary).

This decree came into force on March 7, 1965 — a day burdened with infamy, on which Paul VI, at the Parrocchia di Ognissanti in Rome, became the first pope in history to celebrate Mass predominantly in a modern vernacular language and versus populum (for more on this event, see here and here). In this way, he departed from the constant tradition of the Roman Church. Nor did the people welcome this innovation. The plaque that was placed in the vestibule of the church to commemorate the occasion was vandalized twice until finally it was put in a spot that could not be reached.

Allow me a momentary digression: as Klaus Gamber, Joseph Ratzinger, Uwe Michael Lang, Stefan Heid, and others have demonstrated, the popes who supposedly celebrated “toward the people” at St. Peter’s were in fact celebrating ad orientem because of the unusual situation of those buildings; the location of the people was irrelevant to that primary consideration. Similarly, when worship shifted from Greek to Latin in the fourth century in Rome, the Latin employed for the liturgy was not the everyday street language, as Christine Mohrmann showed in her important lectures published as Liturgical Latin: Its Origins and Character. For those who are interested in a short summary of her findings, see my article “Was Liturgical Latin Introduced As (and Because It Was) the “Common Tongue”?”

Returning now to the Leonine prayers. Although they were officially “suppressed” in 1964, one could just as well say they were made optional, since no attempt was made to prohibit their recitation. Any prayers that carry the Church’s approval for public recitation, such as the Litany of the Saints or the Litany of the Sacred Heart, can be prayed in common in Church after a Mass, provided that no liturgical rubrics are violated. For example, a priest after Mass could emerge from the sacristy, expose the Blessed Sacrament for adoration, and recite one of these litanies with the congregation. The same could be done with the Leonine Prayers.

The prayers after Mass were always precisely that: an addendum, not part of the Order of Mass. They were never printed in the altar missal, though of course they found their way into hand missals for the use of the laity, and the “sacristy manuals” for the use of the clergy had them printed in case of need.

It is comforting to think that traditional Catholics, in communion with all their forebears back to 1859, under the prompting of four distinguished successors of Peter (Pius IX, Leo XIII, Pius X, and Pius XI), have never ceased to pray vocally together after Low Mass in some manner for 165 years and counting.

The richness and beauty of the prayers

We should pause to consider the richness and beauty of these Leonine Prayers, which may be divided into four parts: (I) the prayers to our Lady, consisting of three Ave Maria’s and the Salve Regina; (II) the prayer to God invoking Our Lady, St. Joseph, Sts. Peter and Paul, and all the saints on behalf of sinners and of Holy Mother Church; (III) the prayer to St. Michael asking for his help in our battle against the demons; and (IV) the final threefold invocation to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, beseeching His mercy.

(I)

V. Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

R. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen. (three times)

Hail, holy Queen, Mother of mercy, our life, our sweetness, and our hope! To thee do we cry, poor banished children of Eve, to thee do we send up our sighs, mourning and weeping in this valley of tears. Turn then, most gracious Advocate, thine eyes of mercy towards us, and after this our exile show unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb, Jesus. O clement, O loving, O sweet virgin Mary.

V. Pray for us, O holy Mother of God,

R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ.

(II)

Let us pray. O God, our refuge and our strength, look down with favor upon Thy people who cry out to Thee; and through the intercession of the glorious and immaculate Virgin Mary, Mother of God, of blessed Joseph her spouse, of Thy holy Apostles Peter and Paul, and of all the saints, do Thou mercifully and graciously hear the prayers which we pour forth to Thee, for the conversion of sinners and for the freedom and exaltation of Holy Mother Church. Through the same Christ our Lord, Amen.

(III)

St. Michael the Archangel, defend us in battle. Be our protection against the wickedness and snares of the devil. May God rebuke him, we humbly pray, and do thou, O prince of the heavenly host, by the power of God, cast into hell Satan and all the evil spirits who prowl about the world seeking the ruin of souls. Amen.

(IV)

V. Most Sacred Heart of Jesus,

R. Have mercy on us! (three times)

Intercession of the Saints

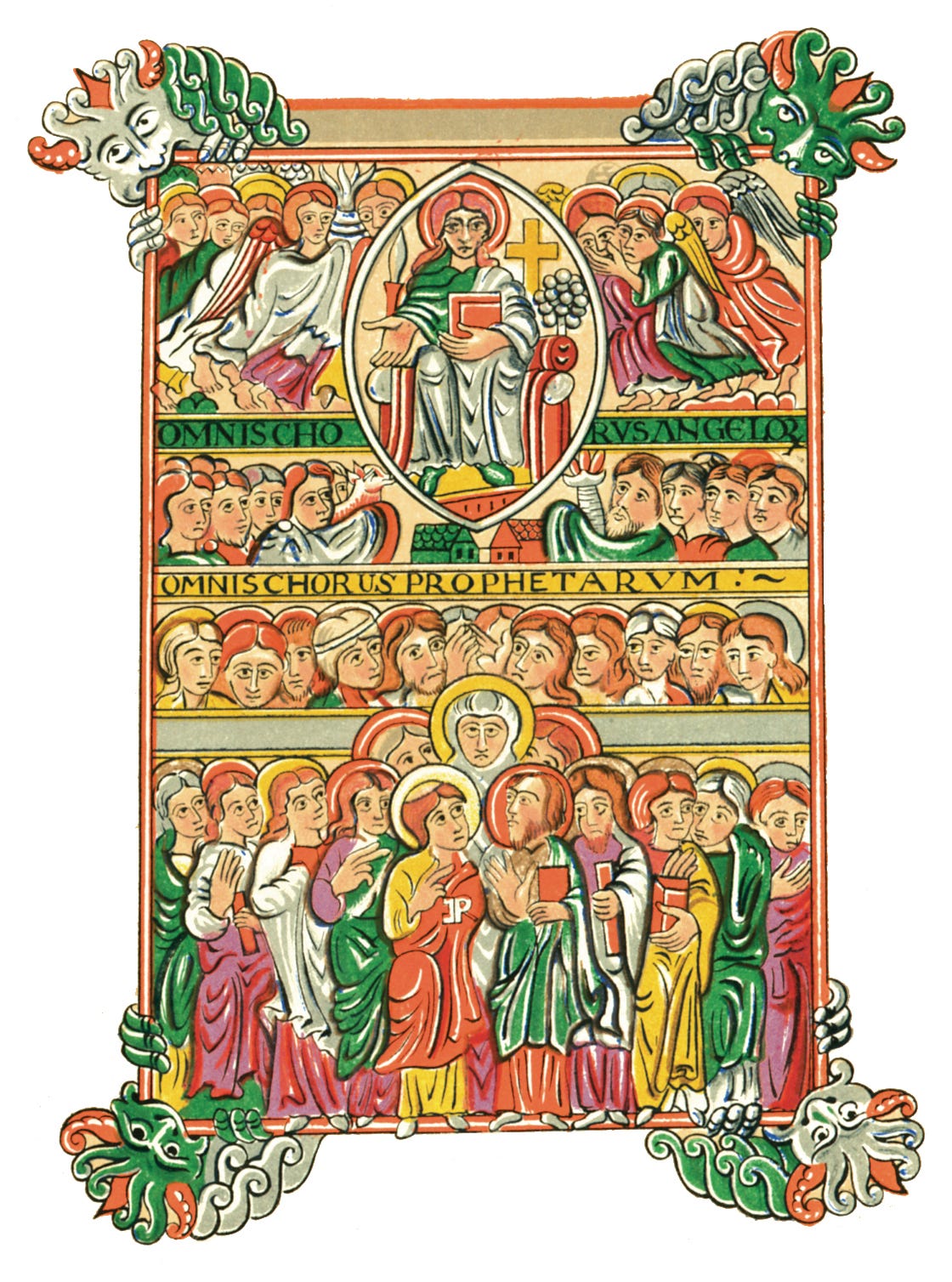

The first thing to notice about these prayers as a set is the strong emphasis on the intercession of the Saints, above all the great Mother of God, Mediatrix of all grace, whose prayers are fervently sought with childlike insistence. Her exalted spouse follows, then the great pillars of the Church of Rome, Peter and Paul, and all the saints, with a special prayer raised up to the prince of the angelic army, Michael (and implicitly, to all the angels of which he is, by God’s grace, the commander).

Every one of us is in constant need of the active help of Mary and Joseph, Peter and Paul, Michael and his soldiers, and all the holy ones of God, for the powers we are fighting against are not powers of flesh and blood but mighty invisible spirits in the high places (Eph. 6:12), forces of evil whose combined power is far too great for any mortals to resist by themselves. Foreign to these prayers is the presumption that we who are God’s children washed in baptism and fed at His table do not stand in need of the continual help of God’s angels and saints. Someone might even quote the verse: “If God is for us, who can be against us?” (Rom. 8:31).

Indeed, it is always enough to have God on one’s side — there is no one stronger! But how does God fight for us, how does He choose to help us? Through His saints and angels, through His servants and ministers, through His faithful ones. This is not a sign of His weakness but an expression of His generosity and power: He makes His whole Church participate in the battle and in the victory. Every member of Christ from lowest to highest has his part to play in the work of redemption, the triumph of good over evil, the conquest of the kingdom of darkness by the kingdom of light. In this way, too, God teaches us humility, dependency, obedience; He teaches us not to rely on our own strength, not to trust our own prayers as though we were already holy and blameless, and not to go into battle without taking our place as a lowly soldier in the vast army of the servants of God.

These are truths we always need to be reminded of, since our fallen tendency is towards the false individualism that entered the hearts of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden. No, we shall not be saved by ourselves, even with God “on our side”; we shall not triumph over evil by ourselves, even if “God is for us.” Because Christ is on our side, we shall be saved by belonging to His Mystical Body; because Christ is for us, we will triumph in the company of all who belong to His Body, and through their help.

By means of the Leonine Prayers, Our Lord never lets us forget the truth that without the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Patriarch Joseph, there would be no Holy Family, no family of God whether in heaven or on earth. Without St. Peter and St. Paul there would be no Church, for the Church is founded upon the Apostles, with Peter at their head; she and her members withstand the gates of hell only when all remain standing upon this hierarchical foundation. Without St. Michael and his soldiers, possessed of intellects far keener than ours and weapons far more damaging to the demons, we could never gain victory in our ongoing warfare against powers as devious and formidable as the ones arrayed against us.

How God Works

The Church rightly emphasizes the countless ways in which God wills that our salvation be worked out hierarchically, all the ways He defends us and sanctifies us through His ministers and brings about our salvation in communion with others and in reliance upon them. At the same time, there is not, nor could there ever be, any conflict between such a cosmic vision and the immediacy of the soul’s intimate union with the Lord. Everything that God does for the soul by means of outward agents, by means of saints and angels, He is also always doing within her.

God alone acts through others in such a way that He is also acting right inside of those He assists by the hands and voices of His ministers. When the Apostles preached the faith throughout the world, it was Jesus Christ preaching in them by the power of the Holy Spirit, and when a pagan took the word into his heart and embraced it, the birth of faith was prompted no less by the Spirit than by the sermon; nay, the sermon had its efficacy from the Spirit, while the Spirit chose to work by means of the sermon.

So, too, when the saints pray for us, their prayer is the Holy Spirit groaning within them on behalf of those for whom they pray, it is the one God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, who mercifully hears the groanings of the saints and grants their prayers for the salvation of the faithful. God is the beginning and the end of the salvation that we, sustained by His grace, work out in fear and trembling (Phil. 2:12)—the salvation strengthened all the while by the saints’ prayers and defended by the angels’ spiritual swords.

In Part 2, I will offer a theological interpretation of the prayers, beginning with their Christocentrism, the centrality of Our Lady, and the rationale behind the specific saints mentioned.

In fact, the full list of times when they are omitted is as follows (from the classic handbook Matters Liturgical):

The [Leonine] prayers are never said after a sung Mass. They are also omitted after the following Masses, when celebrated without chant:

After a conventual Mass (S.R.C. 3697, VII; 4177, II).

After a funeral Mass.

After the privileged Mass of the Sacred Heart and the privileged Mass of our Lord Supreme and Eternal Priest, celebrated on the first Friday and the first Thursday (Saturday) respectively of the month (S.R.C. 4271, II).

After a Mass celebrated with some external solemnity on the occasion e.g. of a First Communion , of a General Communion, of a Confirmation, of an Ordination, of a Wedding, of a religious investiture or profession, of a Jubilee (S.R.C. 4305).

After the first Mass of a priest (see S.R.C 3515, VII)

After a Mass which is immediately followed by some other function or pious exercise, such e.g. as Exposition or Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, an instruction or a sermon, a public Act of Consecration, and the like. It is here supposed that the exercise or function is performed by the celebrant of the Mass and that he does not first retire to the sacristy. If vestments must be removed or changed, this shall be done at the bench (S.R.C. 4305; Eph. Lit.: XLV, p. 303)

After a Mass immediately following the Blessing of Candles, Ashes, or Palms. It is to be noted that such a Mass and the preceding function cannot be celebrated without chant, unless the Memoriale may be used (Eph. Lit.: XLV, p. 303; LV, p. 60; N. 27 D-E)

After a Low Mass on All Souls’ day or Christmas, if the celebrant sings another Mass after it and without first retiring to the sacristy (S.R.C 2926, I).

I remember in my neophyte years attending Mass at the local campus ministry chapel, run by Claretians. The older Claretian priest serving as chaplain there at the time went out of his way to tell the student body not to pray the St. Michael prayer aloud/corporately after Mass concluded. He told everyone that "I'm a big fan of Vatican II" and that the since Vatican II suppressed the Leonine prayers, to not pray the St. Michael prayer. He said one could pray it devotionally after Mass but it seemed that wanted to discourage it corporately.

Also, that same priest kicked out the FOCUS missionaries at the campus chapel because they were orthodox on the "same-sex attraction" issues. He made it seem in his homily announcement that the FOCUS missionaries weren't allowing SSA folks to be apart of the student community (I highly doubt that) and so he was going to get a different group. He was definitely a progressive fellow.

Another interesting historical note is the intention for which the Leonine prayers were prayed. Initially Leo XIII had them being prayed for the liberation of the Church after the Masonic takeover of Rome in 1870 and later after the Lateran Treaty Pius XI retained them for the conversion of communist Russia.