The Reign of Novelty and the Sins of the Times: Why the Novus Ordo Is Solely Modern in Content (Part 3)

In the second part, we saw that a mature liturgy is the fruit of an entire civilization, and that neither a high civilization nor the refined liturgy developed within it can be the product of a particular moment in time or of a narrow clique. Moreover, established liturgy bears within it principles and contents that each generation is obliged to receive with homage and pass on with fidelity, in order not to distort or defile the inheritance with the preoccupations or enthusiasms of any given moment.

Ancient — or ultramodern?

Surely it has not escaped your attention that apologists for the Novus Ordo lean heavily into a certain “selling point” that they repeat ad nauseam, namely, that Paul VI’s rite is better because it has, or restores, so much “ancient content,” and is so much closer to the primitive rite we read about in an author like St. Justin Martyr. This argument, which encapsulates the error known as antiquarianism, can be refuted in two ways.

First, the antiquarians never actually want to restore all of antiquity, but only that part that chimes in with their fancy (exactly the point Shaw made). So they do not want the ancient rules of fasting and abstinence, but when it comes to simplifying rites to make them less demanding, why then they become devotees of antiquity! The same antiquarians actively abolished truly ancient elements already present in the liturgy, such as the Ember Days and Septuagesima (to give only two of many examples), so we know that this appeal of theirs is a smokescreen, a rationalization that they expect ignorant Catholics to swallow without questioning.

Second, the antiquarian position denies the truth of the Church as the living body of Christ that assimilates, grows, and matures into fullness, as the parables of Christ about the kingdom of God imply that it will, and as St Vincent of Lérins demonstrates that it does and should. The claim that we must leapfrog over most of Church history to reach a putative “pure original form” is equivalent to Protestantism’s denial that the Church is governed by the Holy Spirit who leads her into the fullness of truth in all domains. John Henry Newman, after all, argued that good development occurs both in doctrine and in ritual, that it is rightly to be expected and to be welcomed.1 Of course, Newman is emphatic that development is cumulative and continuous — a radical break can only be a sign of error, of “mutation” in the Vincentian sense.

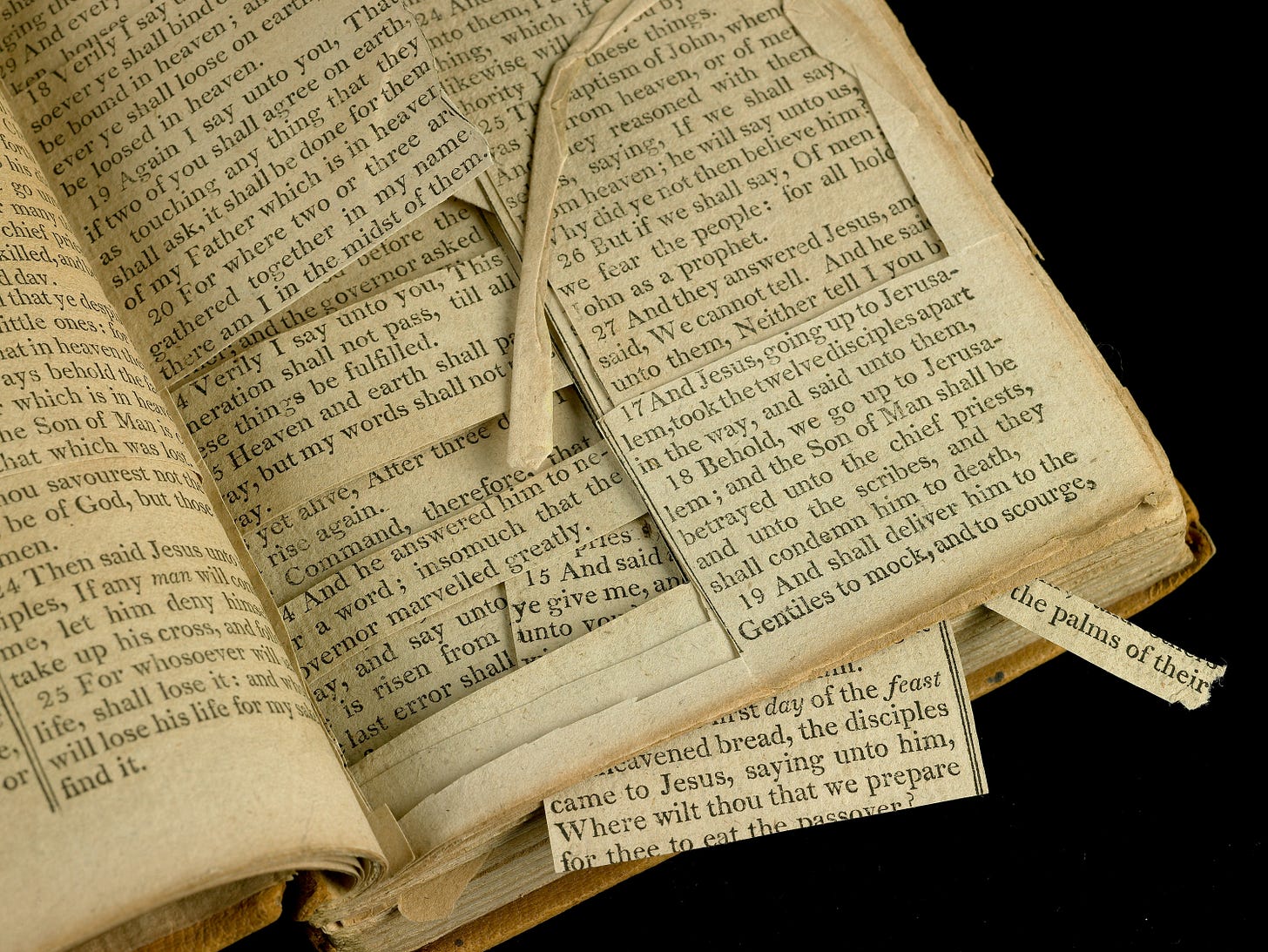

In point of fact, due to its underlying principles, the liturgical reform as it played out could not avoid being a toxic mixture of antiquarianism and modernism. It was antiquarian in that it tried to take pieces that belonged to a less mature phase and reintroduce them later, as if the arms and legs of a child could be reattached to a full-grown man; it was modernist in that it confused profectus or growth with permutatio or mutation, and saw sweeping change as not only possible but also desirable on account of the essentially different worldview of Modern Man, baked in the triple furnace of the Scientific, Industrial, and French Revolutions. Let it not be forgotten that scarcely any ancient text taken up by the reformers was allowed to stand in its original form; nearly every one of them was “redacted,” to use the fancy term, or, in plain English, rewritten according to modern sensibilities. Yet anthropologically speaking, modernism is not a necessity but a choice; a bad choice, at that.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.