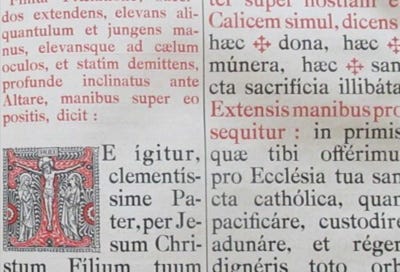

Of all the prayers with which the Roman Catholic Church offers the sacrifice of praise to Almighty God, the one that stands out the most as a touchstone of divine faith, a foundation of immovable rock, a treasure of ages, is the Roman Canon—the unique anaphora or Eucharistic prayer that the Catholic Church prayed in all Western rites and uses, from the misty centuries before the time of Pope St. Gregory the Great (d. 604) until the fateful end of the 1960s. The Roman Canon was, and was always seen as, an apostolic heritage to be lovingly received, jealously guarded, and diligently handed on. The Council of Trent took special pains to praise the Roman Canon: “Since it is fitting that holy things be administered in a holy manner, and of all things this sacrifice is the most holy, the Catholic Church, to the end that it might be worthily and reverently offered and received, instituted many centuries ago the holy canon, which is so free from error that it contains nothing that does not in the highest degree savor of holiness and piety and raise up to God the minds of those who offer. For it consists partly of the very words of the Lord, partly of the traditions of the Apostles, and also of pious regulations of holy pontiffs.” We may imagine it as a kind of sacred “baton” passed from one generation to the next, to insure the continuity of the race we are running in the footsteps of the Apostles Peter and Paul, as we strive to attain the heavenly prize.

In this lecture, I look at twelve dogmatic truths transmitted by the Roman Canon—truths either totally absent from or significantly muted in the new Eucharistic Prayers approved by Paul VI. Then I consider the moral implications of having optionalized the Roman Canon into a state of near oblivion.

Share this post