Tradition as Mine-and-Yours-and-Everyone’s: Overcoming the Peculiar Loneliness of Modernity

Elevated by the Past: The Normative Role of Tradition in Life (Part 3)

Last week, we considered a couple of argumentative strategies to make manifest the good of tradition, its necessity for human flourishing. As with first principles in general, there can be no demonstration, strictly speaking, of this point, but only a manifestation of it to the eye of the mind: the kind of argument, in other words, that leads to an “aha!” moment rather than a “Q.E.D.” Considering that the powerful axioms of thought on which we rely for everything we think and do are of exactly this character—think of “a thing cannot both be and not be at the same time and in the same respect”—we should not regret that we cannot prove it; rather, that would only be one more indication that tradition lies within the realm of principles on which human life depends for its intelligibility.

The good of intergenerational identity

Let us go deeper still, to a third approach: it is simply good for us to be in contact with people who lived before us and who are related to us by different kinds of relationships. Examples will flesh this out.

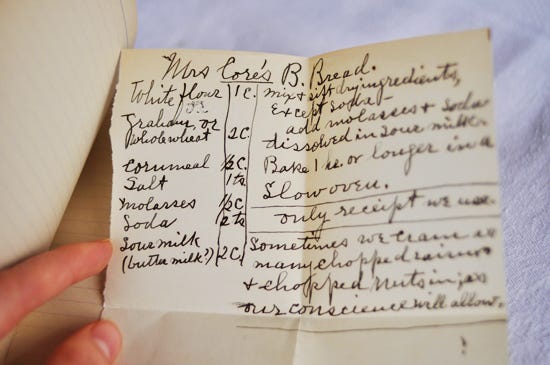

I know a fellow who is living in the house his great-grandfather built. Whenever he mentions this to others, the reaction is spontaneous and always the same: “How cool is that!” (or words to that effect). What’s more, he practices the same profession as his father, who practices the same profession as his father, who practices the same profession as his father, all the way back to that great grandfather. And people usually say, “Wow, that’s wonderful!” Is it necessary? No. But do we see it as a good? Yes, we do. I know another fellow who makes homemade pasta using the same recipe as his grandmother who moved over to the United States from Italy. He does it because it’s great to do it. The pasta tastes good, yes, but it is also simply good to cook with the same recipe as his grandmother.

The reason this is so instinctive is that our social nature—the nature whereby it is good that we are not alone, but in a society—is inherently time-bound. Our instincts are telling us not that it is good to be only with our exact contemporaries, those who are exactly our own age, but rather, that it is good for our lives to overlap with the elderly who went before us and the young who come after us, and to be ourselves young now and elderly later, in company with others. This same instinct tells us that it is good to have children, descendants—and that it is good to have ancestors. We cannot satisfy our social nature by living in contact only with those alive at this exact moment, or only those our own age. And yet, that is where we find ourselves in modernity: our lives typically resemble the lives of our forebears so little that, when we think of it, we feel lonely.

A loneliness without a name

Loneliness arises when one does not live with others. Spouses who cannot have children experience a grief that can be hard to understand until we grasp it as a kind of loneliness—but our languages don’t have a word for the special kind of loneliness of living with no contact with present or future descendants. Similarly, people whose lives are simply cut off at every turn from the past, from their heritage, experience a kind of loneliness, too. For lack of a word proper to it, this feeling is often called nostalgia, and that may be adequate if we mean “nostalgia” in its original sense, as a cosmic home-sickness.

Modernity has a tendency to place us only or primarily with our peers and contemporaries—we see this in public education, where all the pupils in a class are the same age, or at the workplace, where there is usually not so much variety and where “innovation” is the buzzword, or on TV and in the media, where a certain type of adult youthfulness is taken as not just the prime of man, but the only “moment” worthy of attention. Babies and the elderly are socially ignored or hidden away or seen as burdens rather than blessings, because they draw us into the past and into the future. The loneliness of man as a social and cultural animal is overcome only by being in regular contact with our forebears and with our posterity, in the many ways this can take place. The fact that we are cut off from the past in so many ways makes it that much more important to make contact with the past in our religious practices.

Because Catholicism is, and is meant to be experienced as, a strong, visible community, Catholics live out man’s social nature precisely as Catholics. Because of the communion of saints, the Catholic society is inherently trans-temporal. The saints of the past, living in the presence of God, are contemporaries of us who live in God’s grace, but they are precisely the personalities they were—they are not, so to speak, “updated,” as in the aggiornamento called for by John XXIII at Vatican II. Just as the one who lives in his great-grandfather’s house and the one who makes pasta with his grandmother’s recipe love the house and the pasta not only because it’s good but because it has a history and the history belongs to all of the family as intangible spiritual property, so too, Catholics live in the house of faith and prayer that our ancestors built, and we prepare our supernatural recipes with the same ingredients and techniques they used. We want to pray in the same words the saints used when they prayed; we want to pray in the postures they prayed in. This is just something we intuitively know is good: it isn’t something that needs an argument to prove it.

The tremendous break between modernity and pre-modernity at nearly every point of life has led to an astonishing loneliness in our times. But modernity cannot process the experience as loneliness. Modernity’s hallmark is rational management from the third-person perspective, scientific “objectivity,” and when you insist on the so-called “view from nowhere” you have no way of accounting for things that can only be seen from somewhere. So we deal with this loneliness, this enormous lack of connectedness, through what I will call “substitutes for tradition.” We produce sentimental novels or movies or TV shows set in the past. We research our ancestors with powerful online tools and gain lots of head knowledge about our family trees and birth certificates; we might even collect old photographs. We have reference books about saints.

There’s nothing wrong with any of that. But it must be admitted that we could be trying, in these ways, to compensate for the loss of actual connections with the past, such as extended family to live with, an ancestral house to live in, a recipe to cook from, or, most importantly, a liturgy and devotions to pray with. Even as head knowledge can never substitute for heart knowledge, any more than knowing about God can substitute for knowing God and being united to Him in love, so in this matter: knowing about the past can never substitute for being connected to the past in our very lives and practices.

Tradition is communal and community is traditional

At the start of the Bible, God says of Adam: “It is not good for man to be alone.” When He creates Eve, He does not create merely a companion, for that might collapse into mutual solipsism or reciprocal egoism (“égoïsme à deux”). He creates the origin of a family, a tribe, a village, a people, a nation—a Church. It is not good for man to be alone, to be confined to himself, his own world, his own time period, his own generation and its perspective.

(It’s no better, incidentally, to be confined to a very particular time-period of the past, such as the ’60s and ’70s! This is why the criticism that traditional Catholics are guilty of “LARPing” so fundamentally misses the point. They do not experience what they are doing as re-creating a past moment—with costumes, hairstyles, period dialogues, and the like—but as presently entering into something that is timelessly great. If anyone is guilty of LARPing, it would be those who still think and act as if we’re in the ’60s and ’70s, when we’ve long moved on from there!)

It is good for man to look out and look beyond, to look backwards and forwards, to look above him to eternity and around him to all generations past and future. In this way, he overcomes his original solitude and the curse of loneliness.

The authentic Catholic attitude is one of grateful receptivity to an inheritance, piety for our ancestors, humility in the presence of monuments. We trust that God has directed, in broad lines, the worship of the Church in every age, and that the resulting cumulative richness of tradition is eminently good, desirable, beneficial to us, and worthy of attentive discipleship. We are in the position not of masters and owners, but of pupils and tenants. Tradition—especially what we call “immemorial tradition,” something so old that no one can point out where it began or remember who started it—reminds us of, and even makes present in a certain sense, the eternity and immutability of God. Domine, refugium factus es nobis a generatione et progenie: a saeculo et in saeculum tu es (Ps 89:1), “Lord, You have been our refuge through all generations; from everlasting to everlasting Thou art.” There’s a reason Scripture talks about “the everlasting hills”: they’ve always been there and always will be, as a kind of permanent, even unchanging backdrop to the changeable round of daily human life. This is why participating in a liturgical rite that looks and feels ancient is not a form of LARPing, an imaginary visit to a remote past, but instead removes us from our confinement to the present and makes us breathe a different kind of air. It lifts us above the temporal, the ephemeral, the realm of the works of our hands that are perpetually being improved, reviewed, repaired, rejected, replaced.

Other things being equal, I would maintain that traditionalists find themselves less lonely and less lost in modernity, more connected and more contented, because in fact they are experiencing the past as present, tradition as mine-and-also-yours-and-everyone’s, an inexhaustible transmitted content that carries us out of ourselves and out of the prison of the present, the modernism of the moment. We are, so to speak, living in our great-grandfather’s house, which is also ours; we are eating our grandmother’s food, which we know how to make; we are living in the rambling mansion and spacious fields God has provided for us, rather than an efficient but cramped apartment of our own making.

It all goes back to what we think a human being is. The answer to that question will determine what we think a Christian is. How very unnatural and unchristian it is to be untraditional—that is, to think or to behave as if our theology, our worship, our models for life should be newly fashioned ex nihilo (if that were possible) or at least by way of a periodically repeated process of selective recomposition that we can call our own work. What a patchwork of random scraps we will end up with, if we follow that sad path, instead of the ever-surprising and delightful path laid down by generations, led by great-souled men and women (and, we might as well add, by angels who aided them).

Blank slates need full libraries

The title of this essay-series uses the phrase “elevated by the past.” Although each of us starts off in life as a “blank slate” (tabula rasa), we are born into a family, a culture, a heritage. The better this inheritance is assimilated by us, the higher is the basis, so to speak, from which we engage reality.

The low road, rocky, rough, muddy, difficult, circuitous, is the road of the man with little access or attachment to tradition—the feral child of the woods, so to speak—and therefore only his own mental equipment and perhaps a few pieces of equipment borrowed haphazardly from others. The high road, dry, smooth, and more direct, is the road made by the wisdom of tradition.

In the fourth and final part, we will look at why conservatism (as opposed to traditionalism) is a dead end, and why, in spite of the trials of our age, we can and should have hope of better days for tradition and its cultivators.

"I know a fellow who is living in the house his great-grandfather built. Whenever he mentions this to others, the reaction is spontaneous and always the same: “How cool is that!” (or words to that effect). What’s more, he practices the same profession as his father, who practices the same profession as his father, who practices the same profession as his father, all the way back to that great grandfather. And people usually say, “Wow, that’s wonderful!” Is it necessary? No. But do we see it as a good? Yes, we do."

This idea of community across time and of memory is so important that Ruskin considered permanence and memory to be necessary qualities of (good) architecture. He wrote, "I cannot but think it an evil sign of a people when their houses are built to last for one generation only. ... I say that if men lived like men indeed, their houses would be temples--temples which we should hardly dare to injure, and in which it would make us holy to be permitted to live; and there must be a strange unthankfulness for all that homes have given and parents taught, a strange consciousness that we have been unfaithful to our fathers' honour, or that our own lives are not such as would make our dwellings sacred to our children, when each man would fain build to himself, and build for the little revolution of his own life only."

How much worse when we destroy an ancient liturgy and beautiful ancient churches and replace these with barren contrivances of the little revolutions of our time.

"The tremendous break between modernity and pre-modernity at nearly every point of life has led to an astonishing loneliness in our times."

The loneliness of a world where truth is subjective and everything must serve only the instant.

I really enjoy your work Dr. K, I wish there was a way to make Catholics realise what’s been taken away from us. The large majority don’t know about Tradition and don’t care to read. It’s frustrating but I’m hoping articles like yours get circulated across platforms to make catholics wake up and ask their bishops for things Traditional that have been taken away from us.