During my time out of the country, in lieu of the usual Weekly Roundup I offer readers a glimpse into new publications worth attending to. I receive a lot of books from publishers but I present to you here only those that catch my eye as being especially worthy of note. I will present them in thematic groups.

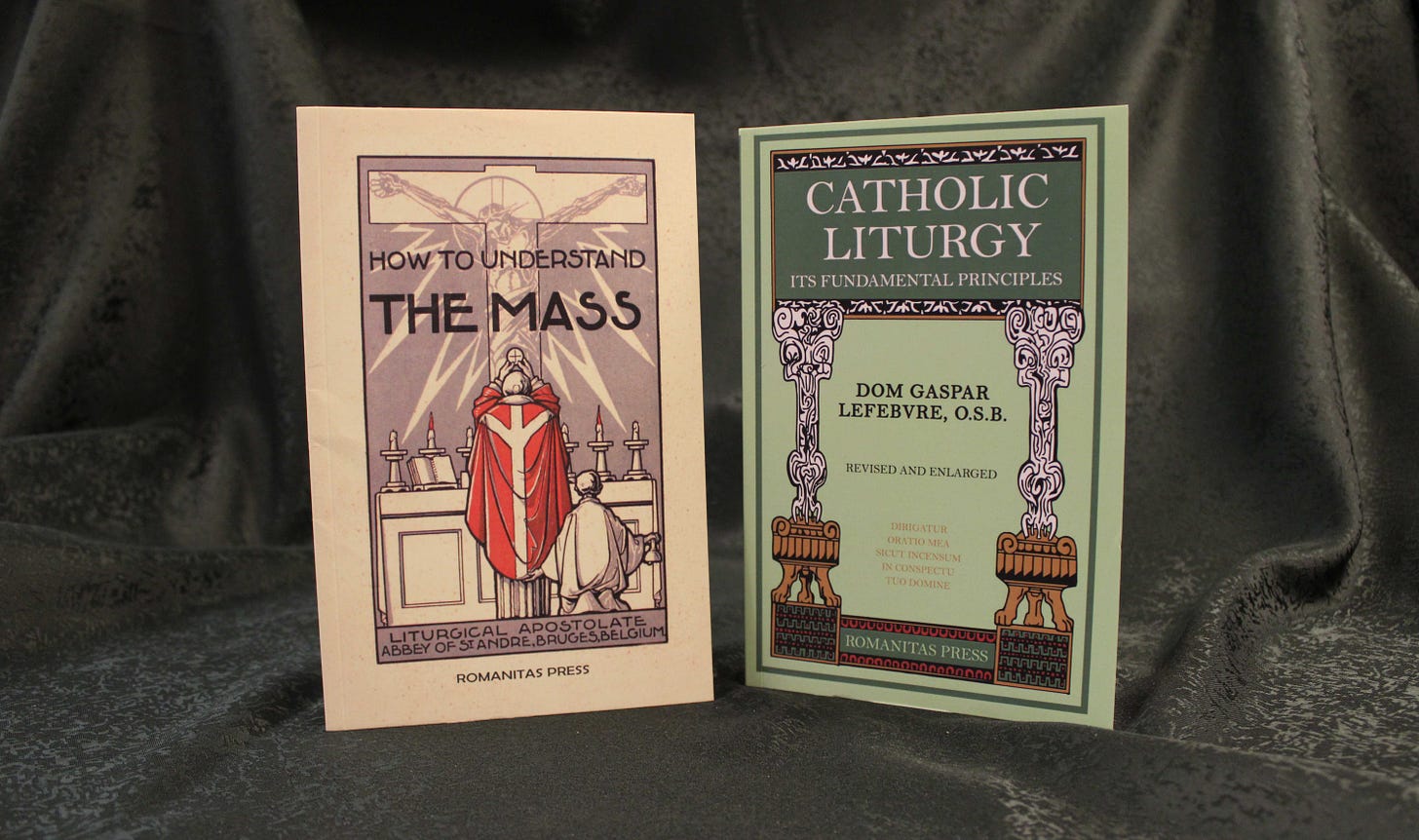

Let’s begin with two books from Romanitas Press.

On the right, we have Catholic Liturgy: Its Fundamental Principles, an enlarged reprint of the 1954 edition:

Dom Gaspar Lefebvre, O.S.B. (1880-1966) is perhaps the preeminent representative of the authentic Liturgical Movement. While better known for his internationally popular St. Andrew Missal, this book—originally entitled Liturgia—is his masterpiece…. Completely re-typeset and reformated for easier reading, each chapter features the lithograph headers and footers drawn by the famed Belgian illustrator, Rene De Cramer, that were included in the original 1924 English edition.

To see the table of contents, visit here.

On the left, another by the same author:

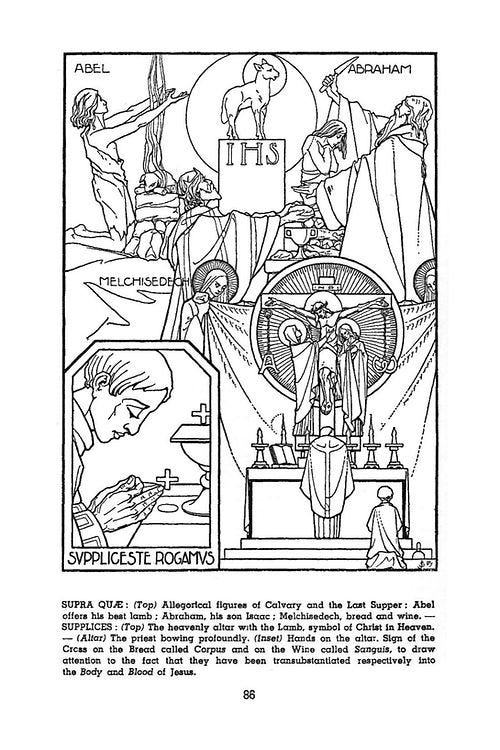

How to Understand the Mass (1959) explains in a simple manner the profound theology of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. It starts with the chapter “What is a Sacrifice?” and then proceeds through the priest's preparations, the divisions of the Mass, and each of its parts, such as the various prayers and actions of the Offertory. Dom Gaspar’s descriptions of the Mass parts are complemented by the evocative and instructive Art Deco drawings of Joseph Speybrouck, a long-time collaborator with the Abbey of St. Andrew. Each illustration takes up a full page and consists of a triple collage: the upper part depicting as scene usually from Sacred Scripture, then below, vignettes of the priest’s action and the corresponding position of the celebrant and acolyte during Low Mass.

This triple illustration feature is quite striking. Here’s an example:

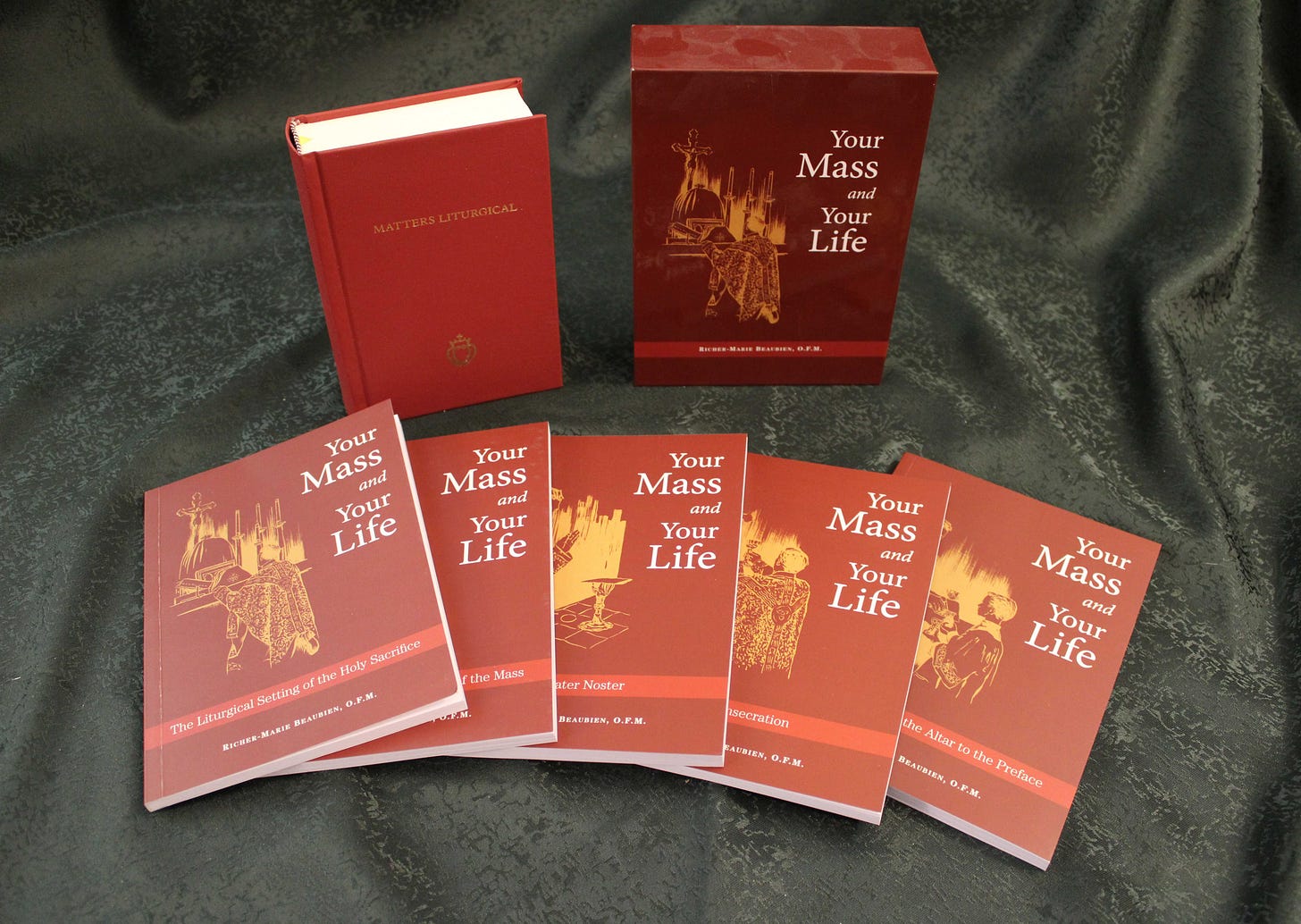

Angelus Press has not been a slacker when it comes to fine liturgical publications:

The hardcover volume in the upper right, Matters Liturgical, complete with ribbon, is as comprehensive and accurate a rubrical guide as any pastor, MC, or sacristan could ever wish to have. I quoted this volume several times in my forthcoming book from Angelico Press, Close the Workshop: Why the Old Mass Isn’t Broken and the New Mass Can’t Be Fixed (of which I’ll tell more when the time is right).

Equally excellent is the five-volume set The Mass and Your Life by Rev. Richer-Marie Beaubien, O.F.M., which come in a handy box, as seen in the photo above.

The purpose of the book [as a whole] is to provide an easy-to-read explanation of the Mass in its broad philosophical meaning as well as its finer details. Very few books have been produced for laymen that explain the Mass so completely. This is a truly important series for all those looking to broaden their understanding and the love of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. This five volume set is also an excellent tool for people coming to the Latin Mass for the first time!

This work was first published in 1960; it is not an SSPX product per se, but a reprint of an old classic, released just before the Second Vatican Council had ripped open Pandora’s Box. One can find in these pages the “tradition and sanity” that was characteristic of the preconciliar Church — that is, quite simply, the Church. Nothing in these books has ceased to be true, and all of it is spiritually profitable.

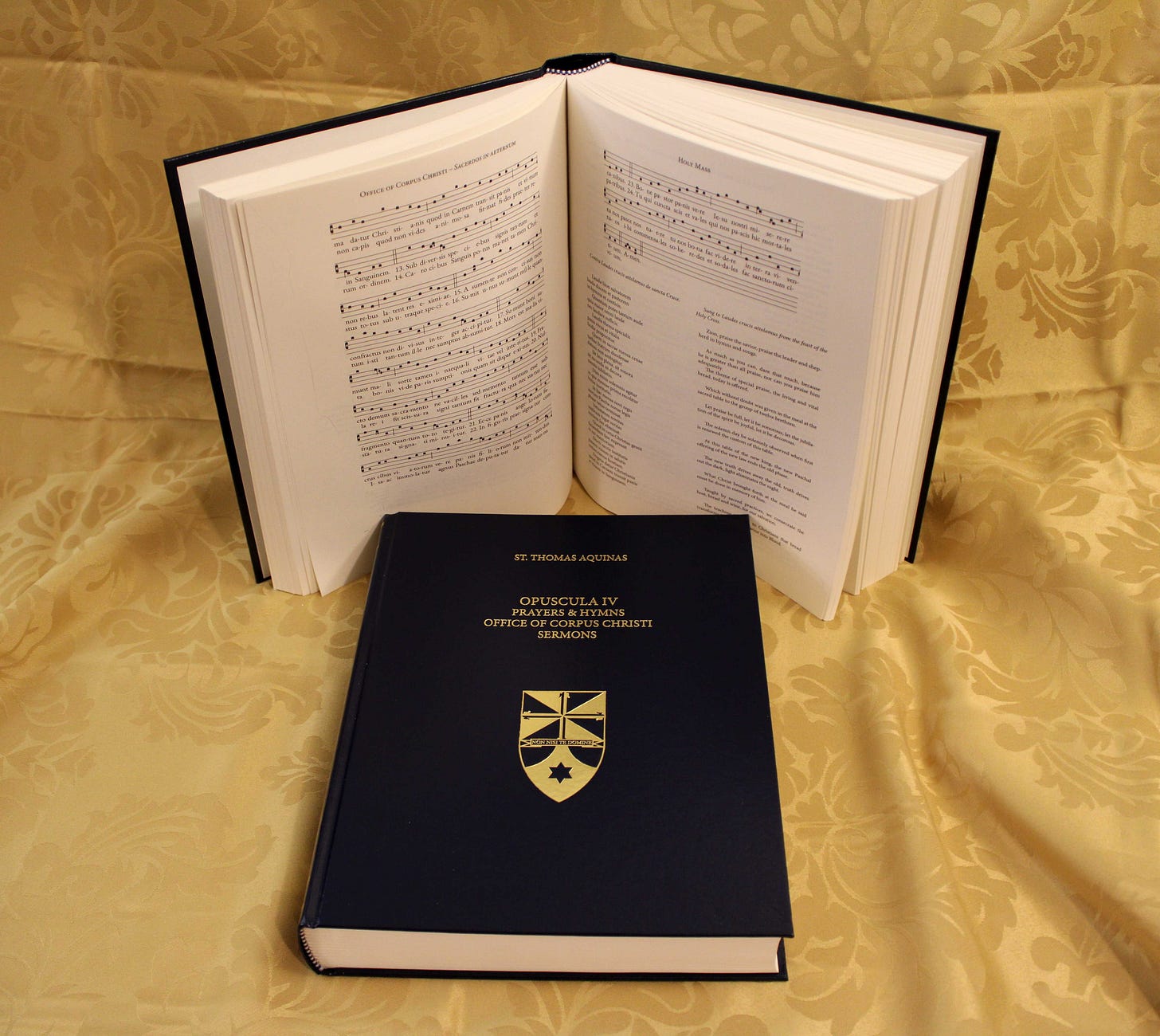

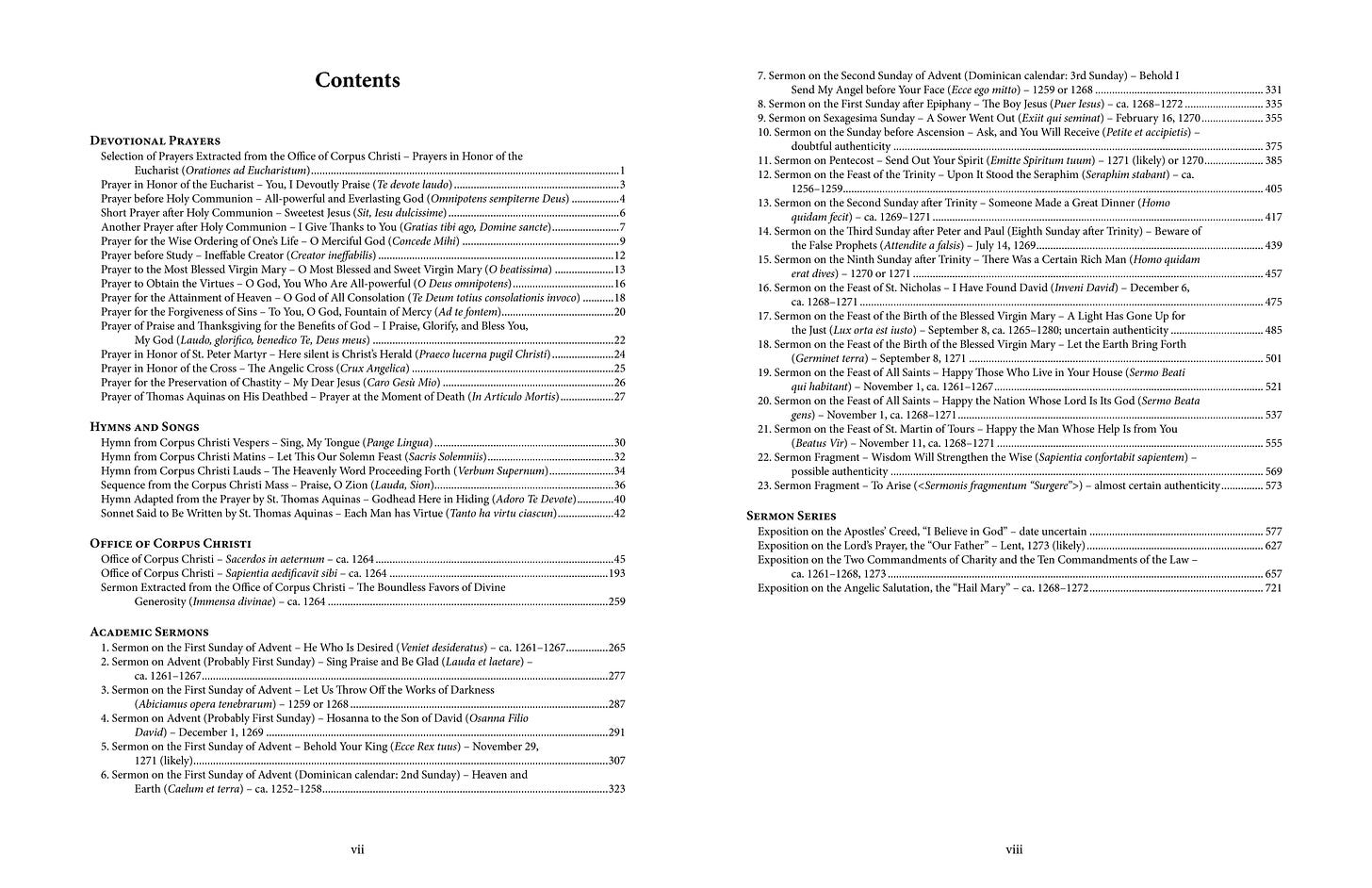

Next, we turn to the latest release in the bilingual Opera Omnia of St. Thomas Aquinas, co-published by The Aquinas Institute and Emmaus Academic:

Here, we behold the volume that contains all that is dearest to my mind and heart about Thomas the mystic, liturgist, and preacher — a side of him very poorly known, much to the detriment of a rounded understanding of his life and teaching (as I’ve shown here at the Substack, and in my books The Ecstasy of Love in the Thought of Thomas Aquinas and Anatomy of Transcendence: Mental Excess and Rapture in the Thought and Life of Thomas Aquinas).

This volume, number 58 in the Opera Omnia, bears the title Opuscula IV: Prayers & Hymns, Office of Corpus Christi, Sermons. The prayers and hymns were translated by Fr. Paul Murray et al., the Office by Vincent Corrigan et al., and the Sermons by Fr. Mark-Robin Hoogland et al. The book weighs in a 726 pages (due to having all the Latin on the left side, all the English on the right, and inclusive of all the Gregorian chants for the liturgical pages). I am happy to say that I participated in this volume as a consultant, as I’ve been involved in other volumes as editor and/or translator.

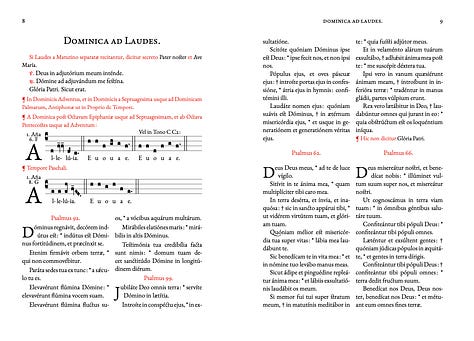

What we find in this book is nothing short of a treasure-trove, glistening with jewels and precious metals. A screenshot will have to suffice to whet the reader’s appetite:

Also recently announced: for the first time ever, the whole of Book 1 of Aquinas’s Sentences Commentary has been translated. The two volumes (again, as always, with Latin and English side-by-side) are ready for pre-order. You can find discount information here. I can tell you, as someone who has spent a lot of time in the Scriptum Super Sententiarum, that these volumes are doubly valuable: the Latin text is the best currently to hand, and the translation is accurate.

Now for some new items from TAN Books:

Here we have some very interesting publications indeed. At the extremes of the photo, two small booklets, each readable in a single sitting: Pope Benedict XIV’s (N.B.: not Benedict XVI’s!) defense of Latin as a liturgical language, and St. Vincent Ferrer’s short exposition of the Mass as an allegory of the life of Christ.

I’ve mentioned before the glorious resurgence in awareness of and publications about the “spiritual interpretation” of the Mass that flourished from the early Middle Ages through the Baroque period until it was frowned upon and dismissed by modern liturgists, trapped in their literalism and utilitarianism. In a similar vein to St. Vincent Ferrer’s but more detailed is St. Bonaventure’s Expositio Missae, where the Seraphic Doctor draws out the layers of meaning and symbolism in the actions of the Mass, having as his goal that the reader shold “hear the most holy Mass with the greatest possible devotion and reverence.” Those who enjoy commentaries on the Tridentine rite will certainly want to add these two to their collections.

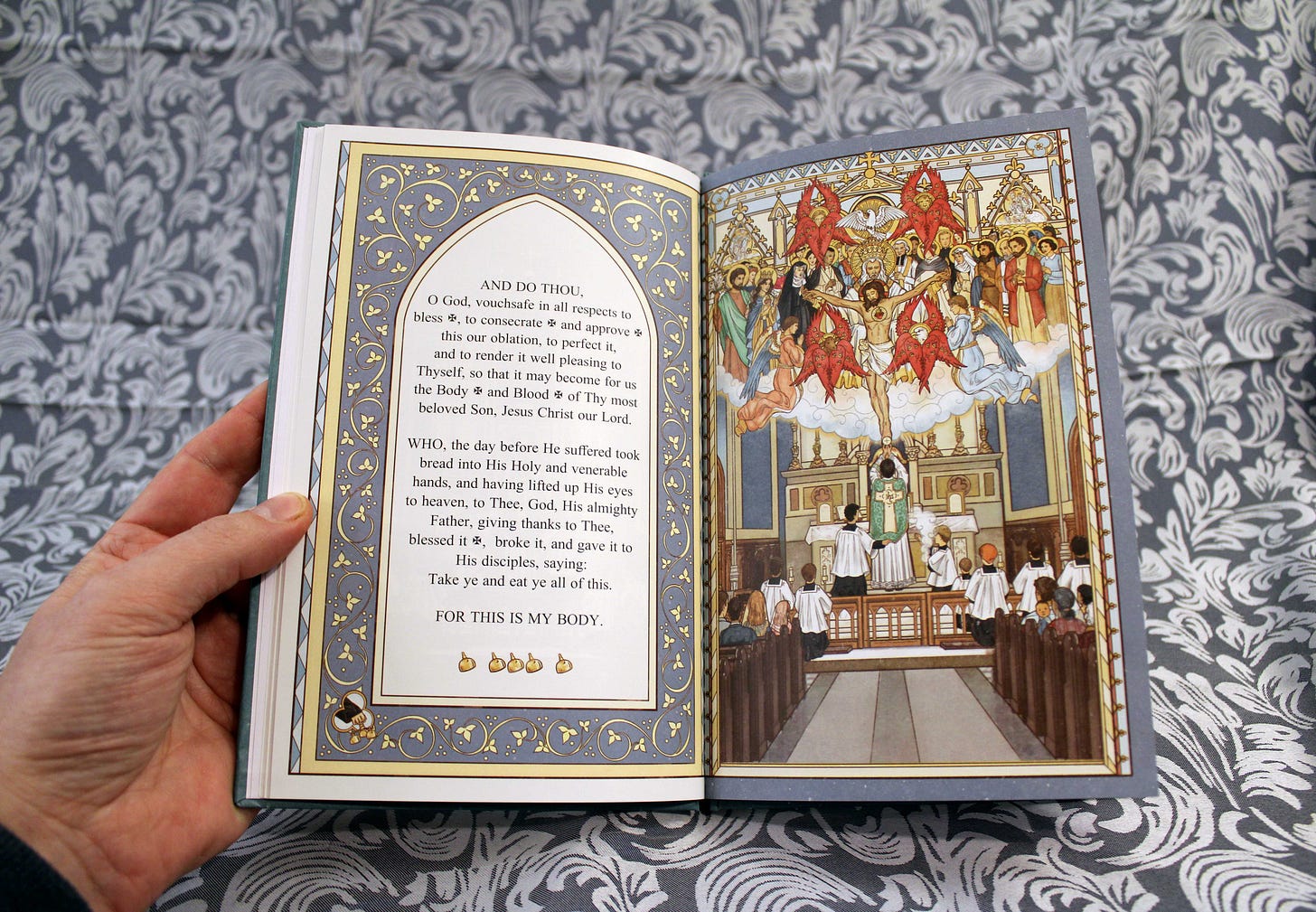

Lastly, Adalee Hude has given us An Introductory Latin Missal for Children. Major parts of the text of the old Mass are present herein, closely followed by English translations; but the illustrations are really the glory of this book. Hude has drawn inspiration from medieval illuminators and Liturgical Movement artists to create detailed evocations of what is happening invisibly at the Mass at various moments. Of course we know that the invisible is by definition incapable of being seen with human eyes, but there are ways artists can “lift the veil” a bit to allow us to catch a glimpse of realities too awesome and divine for our comprehension:

The art in this book is quite dense in content, but this is all the more reason why I’m confident children would be fascinated and absorbed by it — which brings not only catechetical benefits but also a welcome spell of quiet good behavior during a long sung Mass or solemn Mass!

There are many lovely details in the book. One of my favorite is when the illustrator depicts, kneeling along the communion rail, figures from many periods of history, from ancient times down to the present. This is a clever way of conveying the truth of the diachronic unity of the Church, that is, that the Catholic Church is the same across the ages — something our traditional Latin liturgy brings out very well in all kinds of ways.

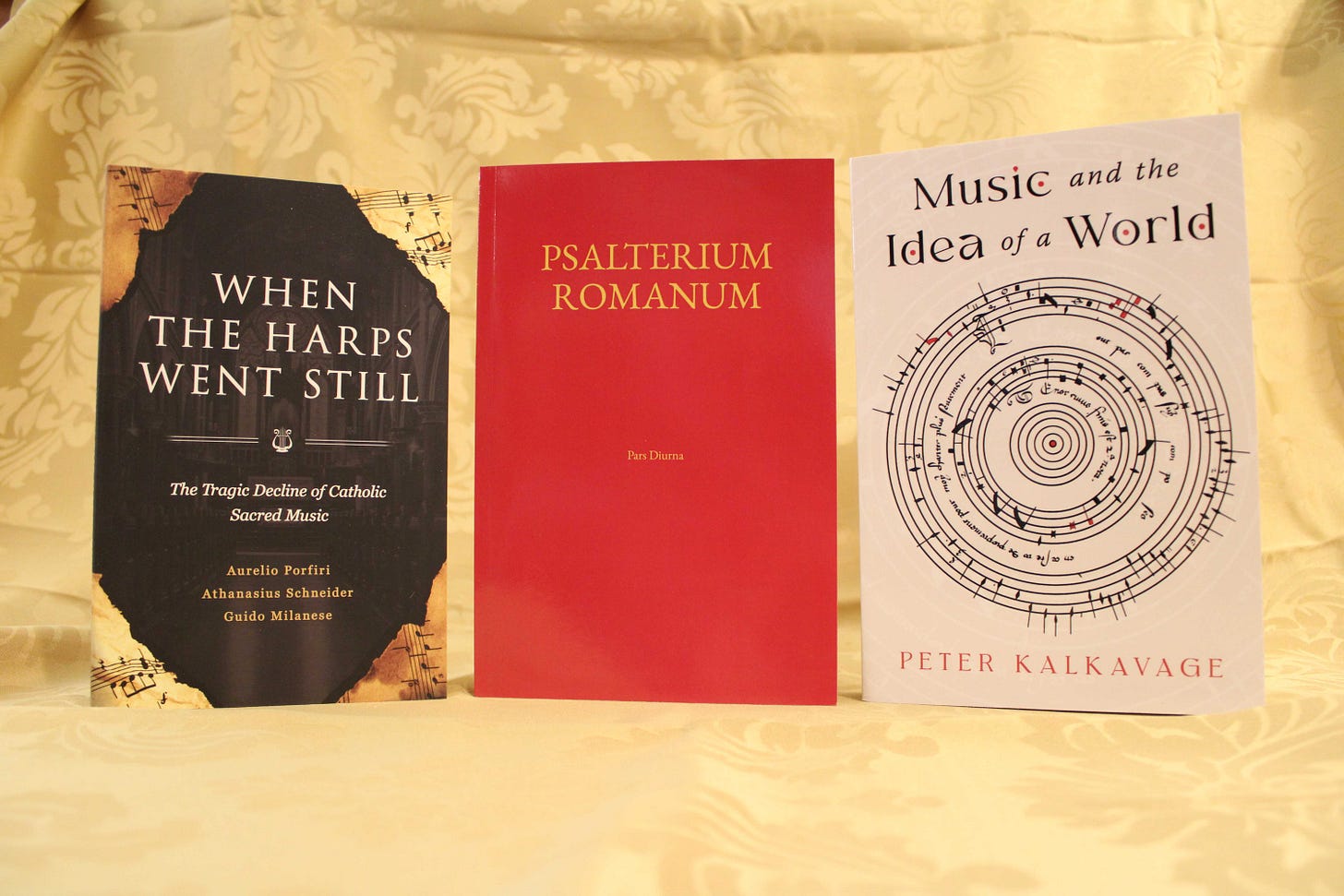

Our next trio of publications is for singers and music lovers:

When the Harps Went Still: The Tragic Decline of Catholic Sacred Music brings together the insights of Aurelio Porfiri, Bishop Athanasius Schneider, and Guido Milanese on a crucial topic, one that has often been mentioned on this Substack: the rise and fall of appropriate music for Mass. The book is rich in historical, cultural, and psychological considerations, and should be read by anyone with a serious interest in the topic. I would have to say it is somewhat weaker on the liturgical side of the problem and does not seek to engage with the question of the morality of different types of music or the question of silence; my own book Good Music, Sacred Music, and Silence is more comprehensive and delves deeper into the relevant issues. Nevertheless, I did find this new book stimulating and well-argued.

Music and the Idea of a World, written by longtime St. John’s College tutor Peter Kalkavage, is a very profound study, which, while lucidly written, is a demanding read — one I’d recommend especially for philosophically-minded musicians or musically-minded philosophers. Here’s the blurb I wrote for the back cover: “Music is the language of the cosmos and of the human soul, and inevitably reflects—and inculcates—a vision of reality as a whole. The ancients and medievals honored it as one of the seven liberal arts, keys for opening the doors to wisdom. Peter Kalkavage patiently and beautifully unfolds neglected but profound truths about this mysterious art, as he shares with readers the fruit of decades of teaching the Great Books and leading students into the mysteries of tones, rhythms, and harmonies. Illustrating his themes with aptly-chosen composers and works, Kalkavage treats his subject with an eloquence and authority that make Music and the Idea of a World a sheer joy to read.”

Readers of Tradition & Sanity are probably aware by now of the movement to restore the “pre-55 Roman Rite” of Mass — that is, the rite in direct continuity with its 1570 canonization by St. Pius V, and without the serious deformations introduced by Pius XII, above all his Holy Week of 1955, which survived for only 14 years before being indecorously swept away by Paul VI’s Holy Week of 1969. Compared to these johnny-come-latelies, a Holy Week tradition of more than 1,000 years’ standing is far worthier of our cultivation.

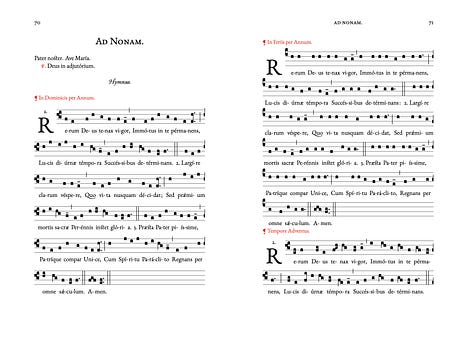

Within the pre-55 movement there is a desire to somehow find our way back to the pre-Pius X breviary, which Bishop Schneider calls “The Breviary of the Ages,” in parallel to the Mass of the Ages. The Divine Office presents a much more complicated set of issues than the Mass does. Nevertheless, it seems important simply to have tools to begin rediscovering and recovering the Breviary of the Age — and a crucial tool has just been provided by Gerhard Eger, editor of the Psalterium Romanum.

This volume contains the entire ferial Office for the day Hours — Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline — according to the Roman Breviary of 1568. For the first time since the Solesmes reforms of Gregorian chant, the text is supplied with full musical notation. Also included are the seasonal Paschal antiphons, as well as the hymns, versicles, and short responsories said during Advent, Lent, Passiontide, and Paschaltide. For those aware of the “inside baseball,” this means the ancient Roman cursus psalmorum or cycle of psalms (largely abandoned by Pius X), the ancient hymns before their classicizing rewrites by Pope Urban VIII, and the antiphons that would have been familiar to most of our great saints in the West. This book, available from Amazon sites, is indispensable for anyone who wishes to sing the entirety of the old Roman diurnal Office.

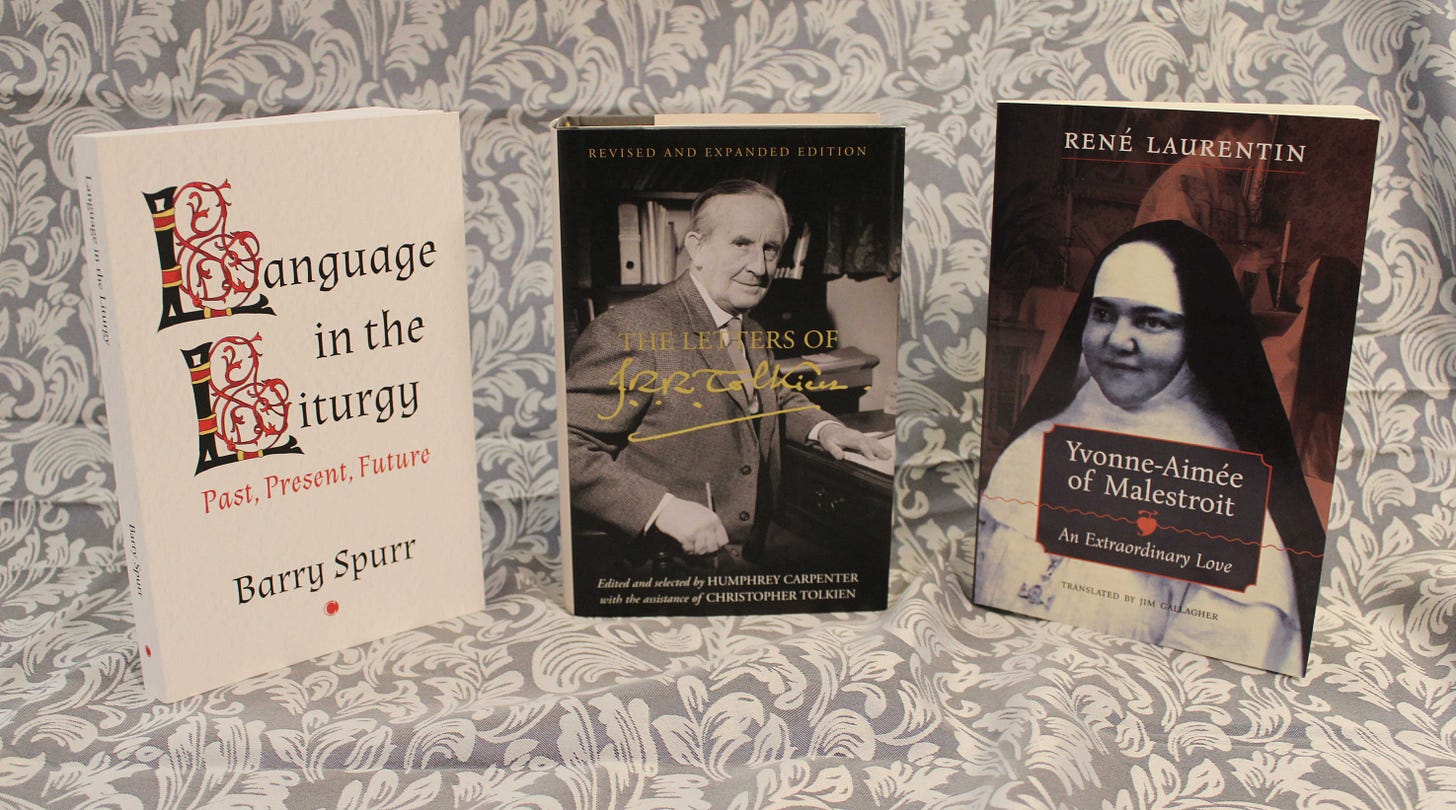

Our last trio gives us a treatise on liturgical language, a new-and-improved old classic, and a first-ever book-length biography in English of a monumental mystic of the last century.

The book in the center hardly needs much commentary; any lover of Tolkien will be familiar with The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien edited by Humphrey Carpenter. But… in case you haven’t heard: a new edition was published in 2023 containing many more letters than the first, including some real corkers. Helpfully, the original numbering system was preserved, with additional letters marked by letters after numbers. I’d say this is one of the top five most essential non-fiction Tolkien books to have.

The one on the left, Language in the Liturgy, Past, Present, and Future by literature professor and T.S. Eliot expert Barry Spurr, is a superb treatment of the question of what is the right “register” of vernacular language in the liturgy (if it is to be used at all), and a decisive, even definitive refutation of the typical approach to translation and adaptation dominant in both the Anglican and Roman Catholic worlds. His careful analysis of liturgical language is illuminating even for those who (like myself) advocate only Latin in the Latin rite, and his treatment of the “feminisation and infantilisation of liturgy” has the sparkling quality of that old classic Why Catholics Can’t Sing. Members and admirers of the Anglican Ordinariates will particularly want to read this book. Here was the blurb I contributed for the back cover:

Spurr has demonstrated past all gainsaying that the use of a “high language” in liturgy — which comprises not only speech but also music, vesture, regulated actions — is no mere aesthetic fancy but a constitutive element of identity, piety, catechesis, and fervor.… Spurr’s razor-sharp critique and his animated apologia place us doubly in his debt.

I’ve saved the most intriguing and unexpected for last: René Laurentin’s Yvonne-Aimée of Malestroit, An Extraordinary Love. Mother Yvonne is one of my favorite modern saints (in the broad sense; she’s not yet canonized), one to whom I pray every day, yet one who has not received her due in English owing to a dearth of material on her. That has changed decisively with the translation of this excellent biography, of which I was able to read the page proofs. I supplied the following endorsement for the back cover:

In a Church whose history is already rich with extraordinary mystics and mystical phenomena, Mother Yvonne-Aimée seems to belong to a category entirely her own. Showered beyond compare with miraculous gifts—to such an extent that all writings concerning her were suppressed by the Holy Office in 1960 to avoid erroneous preoccupations and deductions—this steadfast nun, in her day-to-day life, expended her considerable energy on serving her sisters, neighbors, enemies, and correspondents, generously sharing with them the warmth of love and the light of wisdom that God made to flow like a torrent within her. The translation of René Laurentin’s carefully researched biography dramatically improves our English-language resources on Mother Yvonne-Aimée, bringing her the attention she deserves as a witness to the grace and power of God in our midst.

To put it as simply as possible, Mother Yvonne is like a female version of Padre Pio, only even more amazing in some ways.

On one occasion, the Lord Jesus appeared to her and taught her to say this prayer: “O Jésus, roi d’amour, j’ai confiance en votre miséricordieuse bonté.” O Jesus, King of Love, I put all my trust in Thy merciful goodness (or, Thy loving mercy — it can be said either way). The Vatican approved the prayer not long after she received it, and it has been quite popular in some circles (especially French) ever since. I learned it many years ago and it has become one of the most frequent exclamations on my lips.

The statue associated with this devotion to Jesus, King of Love, looks like this (we have one in an alcove next to our kitchen):

Thank you for reading Tradition & Sanity and may the King of Love bless you and yours.

We’ll resume our Weekly Roundup next week, when I’ll be back home from pilgrimage.

Dear Prof Kwasniewski, I think you’ll be amused: I ordered a hard copy of The Iron Sceptre (Os Justi) from Amazon, and began reading it. Wow, I thought, this is a very weird way to start this book! I finished the first chapter which was about a murder in Greystone Park in England and thought, ok, maybe Fimister is going to make an early point about evil. But it seemed so weird.

So I checked the book again and Amazon had put the wrong book in the right jacket!😱😱😱😱

Replacement is on the way. 👍

Now you’ve done it again, Dr K! How can my little budget sustain all these wp]wonderful books you tell us about? Seriously, thank you for bringing these books to our attention.