Vindicating Mystery Against Its Rationalist Enemies

Or, Why It Is Better Not to Understand Everything Immediately — Conclusion

As we have seen, St. Augustine maintains that God at times makes the path to Him difficult for us in order to challenge and provoke us, and to reward us for our efforts. The saint has put his finger on a crucial aspect of human psychology: what is easily won is easily dismissed. This is why low-commitment, watered-down Christianity is failing in the “marketplace of ideas,” but religions and sects that demand everything are thriving; indeed, a modern Western “seeker” is more likely to travel around the globe to seek enlightenment from a snake-charming guru sitting on nails than to visit a local Catholic church where the religious practice is suburban, conventional, and banal.

Far removed from St. Augustine, a twenty-first century Jesuit — guess who! — complains, in a letter called Desiderio Desideravi, about liturgy that employs a “sense of mystery” (!), a “being overcome in the face of an obscure reality or a mysterious rite.”

From the context, Pope Francis—for he is the one who signed his name to that error-saturated document—seems to have in mind things like the priest “with his back to the people,” prayers said sotto voce in a sacral tongue, clouds of incense blurring the line of vision, the ringing of little bells and big bells during the elevations of the host and chalice, the making of many signs of the cross to which medievals attributed allegorical significance.1 Such things heighten the feeling of something special, different, strange, beyond reach, something that is in our midst but somehow off limits, beyond our control and demanding our utmost respect.

The pope, in company with professional liturgists, has no patience for such things: “If the reform has eliminated that vague ‘sense of mystery,’” he writes, “then more than a cause for accusations, it is to its credit.” How can one not be reminded here of Alexis De Tocqueville’s description of American frontiersmen—a description that equally befits the modern Europeans who drove the liturgical reform:

As it is on their own testimony that they are accustomed to rely, they like to discern the object which engages their attention with extreme clearness; they therefore strip off as much as possible all that covers it, they rid themselves of whatever separates them from it, they remove whatever conceals it from sight, in order to view it more closely in the broad light of day. This disposition of mind soon leads them to condemn forms, which they regard as useless and inconvenient veils placed between them and the truth.2

Yet when we try to expose the nakedness of reality, we are stymied; just as we understand one thing, we stumble upon another gap we cannot cross. By the time we learn to cross it, another gap has opened. Can we truly deny that life, the soul, the universe, reality, above all God and the things of God, are deeply mystifying and cannot be stripped bare “in the broad light of day”? To write off the “sense of mystery” would betray a Kantian belief that the human mind is capable of wrapping itself around God’s revelation and digesting it for breakfast: “religion within the limits of reason alone.”

Mystery is truth that is luminous and yet inexhaustible, unconquerable. As in Rudolf Otto’s definition of the sacred, mystery is both fascinating and overwhelming, even at times terrifying. Mystery is ineluctably mystifying. Jesus mystified His parents and His apostles. He remains for all time the prince of peace and provoker of paradox, the Truth that gives Himself to us not as a tidy possession but as a Life to live and a Way to follow. We are promised that at the end, when we pass through the final mysterious gate of death, we will see Him face to face, gaze upon His beauty, understand Him at last—but still not comprehend, for only God is fully transparent to Himself. There’s not the remotest possibility of boredom in heaven; we are too busy resting in the Eternal Act, too enamored of Love to fall back on ourselves.

What do we mean by “mystery” anyway?

As a professor of theology, I often wondered what new college students were thinking when they heard the word “mystery” in class. In the wide world out there, I suspect that the term only comes up in connection with novels, where the “mystery”—that is, the initially unexplained crime, usually murder—has to be figured out, the clues deciphered, the inexplicable accounted for, by a brilliant detective who, as we say, “solves the mystery.” The term means nothing other than a set of circumstances that are temporarily obscure due to lack of data and intellectual acumen. It is something that can be solved: the mystery is something you intend to get rid of, if you can.

Another place where you find the word in common use today is in the David Attenborough-type nature programs, whose narrator will say something like this: “The brown-crested billy-bong-bird’s predilection for a diet of poisonous purple fungus is a mystery to ornithologists to this day”—implying that they just haven’t figured out the answer yet, but stay tuned for next year’s documentary.

To clear away these distracting reductionist meanings, I made a point of asking my students in theology class what we mean when we say that, for example, the Blessed Trinity or the Incarnation is a mystery. They usually say: “A mystery is something you can’t understand, something you don’t see and can’t explain, a secret or a puzzle or a paradox. But maybe it will all get cleared up in the next life: God’s a mystery to us here below, but surely, He’s plain as day in the world to come?”

It is a moment of special joy to be able to say in response: “Actually, no—God is an infinite mystery that can never be fathomed or comprehended. He will be a mystery to us forever in heaven, indeed more than he is now.” But this assertion demands unpacking if one doesn’t wish to be a tease. Fortunately, the heavy lifting has been done by one of the most brilliant theologians of modern times, Matthias Scheeben, whose writes in his masterpiece The Mysteries of Christianity:

Christianity entered the world as a religion replete with mysteries. It was proclaimed as the mystery of Christ (Rom 16:25–27; Col 1:25–27), as the “mystery of the kingdom of God” (Mk 4:11; Lk 8:10). Its ideas and doctrines were unknown, unprecedented; and they were to remain inscrutable and unfathomable. The mysterious character of Christianity, which was sufficiently intelligible in its simplest fundamentals, was foolishness to the Gentiles and a stumbling block to the Jews; and since Christianity in the course of time never relinquished and could never relinquish this character of mystery without belying its nature, it remained ever a foolishness, a stumbling block to all those who, like the Gentiles, looked upon it with unconsecrated eyes or, like the Jews, encountered it with uncircumcised heart….

The greater, the more sublime, and the more divine Christianity is, the more inexhaustible, inscrutable, unfathomable, and mysterious its subject matter must be. If its teaching is worthy of the only-begotten Son of God, if the Son of God had to descend from the bosom of His Father to initiate us into this teaching, could we expect anything else than the revelation of the deepest mysteries locked up in God’s heart? Could we expect anything else than disclosures concerning a higher, invisible world, about divine and heavenly things, which “eye hath not seen, nor ear heard,” and which could not enter into the heart of any man (cf. 1 Cor 2:9)?...

Mysteries must in themselves be lucid, glorious truths. The darkness can be only on our side, so far as our eyes are turned away from the mysteries, or at any rate are not keen enough to confront them and see through them. There must be truths that baffle our scrutiny not because of their intrinsic darkness and confusion, but because of their excessive brilliance, sublimity, and beauty, which not even the sturdiest human eye can encounter without going blind….

Only God’s cognition excludes all mysteries, because it springs from an infinite Light which with infinite power penetrates and illuminates the innermost depths of everything that exists….

Mysteries become luminous and appear in their true nature, their entire grandeur and beauty, only when we definitely recognize that they are mysteries, and clearly perceive how high they stand above our own orbit, how completely they are distinct from all objects within our natural ken. And when, supported by the all-powerful word of divine revelation, we soar upon the wings of faith over the chasm dividing us from them and mount up to them, they temper themselves to our eyes in the light of faith which is supernatural, as they themselves are; then they display themselves to us in their true form, in their heavenly, divine nature. The moment we perceive the depth of the darkness with which heaven veils its mysteries from our minds, they will shine over us in the light of faith like brilliant stars mutually illuminating, supporting, and emphasizing one another; like stars that form themselves into a marvelous system and that can be known in their full power and magnificence only in this system.3

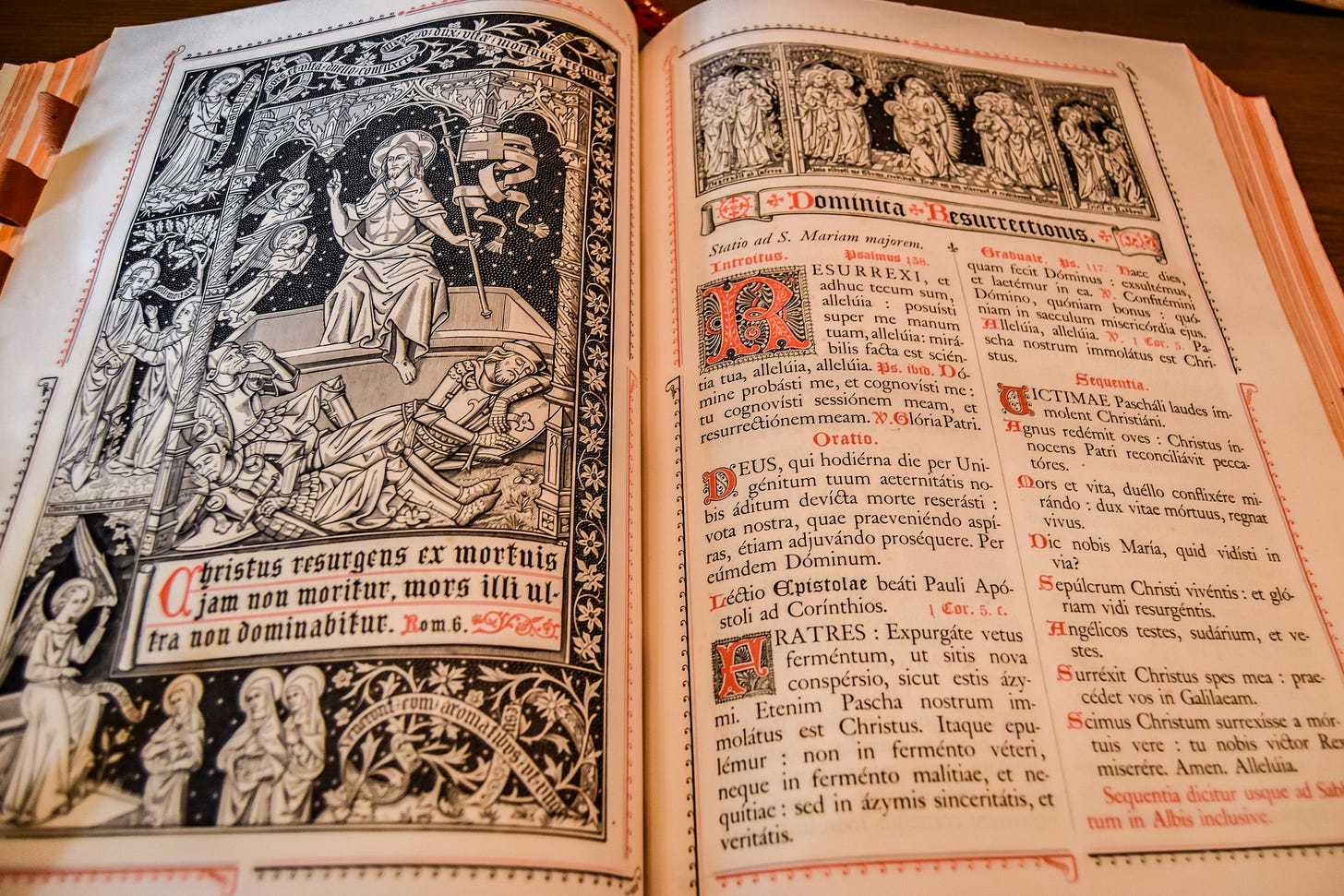

Many of the points made by Scheeben have their analogy in the experience of the traditional Latin Mass. There we encounter a world of mysteries, interlaced and overawing, in which God is at home and we are, so to speak, the outsiders who have dared to enter. Our intellect is never fully adequate to the sheer massiveness and volume of what we behold, in part because it is presented to us in a density of overlapping words and actions that go beyond the powers of any one finite agent to grasp. Not everything “makes sense,” even after many visits.

Thank God for that. My mind, your mind, is too small to compass the elaborate language of encounter distilled over thousands of years of pagan, Jewish, and Christian worship. We are allowed to be there and to absorb what we can, when and as we can, because it is good. “Master, it is good for us to be here…” (Lk 9:33). There is always plenty going on “up there” in the sanctuary, but also a strange serenity all around, at times so palpable it feels as if time has stopped, space has condensed, eons have collapsed, individuals have coalesced around the sovereign Other who is “more within than the innermost in me and higher than the highest in me.”4

“Lost in wonder at the God Thou art”

The specific perfection I have tried to describe is one that authors on the subject frequently circle around as they seeks words for something at once obvious and subtle. Fr. Spataro observes:

Reason is not tempted to be puffed up, as happens in the revolutionary process, because in the old rite not everything can or ought to be explained by reason which, for its part, is content to adore God without comprehending Him.5

Another commentator on the ancient Mass notes the supreme fittingness of the silence that descends on a church during the Roman Canon:

The silence also harmonizes with the mystery of Transubstantiation, in which the material elements of the bread and wine are changed into the Body and Blood of Christ, without the senses perceiving it or the created mind [being] able to comprehend it; the Real Presence and sacrificial life of the Savior under the sacramental species are concealed beyond all discernment. So the holy silence is quite suited to indicate and to recall the concealment and depth, the incomprehensibility and ineffableness of the wonderful mysteries enacted on the altar. “The Lord is in his holy temple; let all the earth keep silence before him!” (Hab 2:20)

Descriptions like these match my own experience and that of many others who have shared their stories with me over the years. For us, one of the great and consistent attractions of the traditional Roman liturgy is that it precisely does not attempt to hand itself to us on a platter, affirming our rationalistic tendencies and patting us on the back for participation (“‘A’ for Active!”). Instead, it keeps its focus inflexibly on God and seems almost indifferent to whoever is around. The copious rubrics make the priest an “animate instrument,” to recall St. Thomas Aquinas’s placid description. We are allowed to be anonymous, quiet, focused, free—“lost, all lost in wonder at the God Thou art.”6 A lady with whom I was corresponding wrote to me:

I continue to be awestruck by the overwhelming sense of God’s presence in the TLM. I’m still reeling from the contrast [with where I used to go] but in a good way. I finally understand all of the references to the Mass as a cosmic reality. I finally understand why preconciliar authors attained to such profundity and to such reverence for the Mass. I keep waiting for all of this to wear off as novelty recedes, but it isn’t wearing off. Deep down, I don’t expect it to.

As to that last sentence: I myself have been attending the old Latin Mass for over thirty years, and the sense of wonder, the regimented peace, the freedom of prayer, the desire awakened again and again for God, the joy (and frankly relief) of never seeing any human being as the center of attention—“all of this” hasn’t worn off. The old rite is ever-new and ever-renewing. This “time outside of time,” this immersion in God, has become the haven of my heart; it structures my day, my week, my life. I could not live well without it.

Wonder is meant to lead to wisdom

A final clarification is in order. My thesis is not that we should just float sleepily in a sea of confusion. “Not understanding” is beneficial to the extent that we seek to understand, just as wonder should provoke us to go “further up and further in.” For we are driven by grace to the vision of God, and likewise we are driven by grace to know the meanings of Scripture and to know the meanings of the liturgical rites. The lover wants to know the beloved and everything about the beloved. A laziness contented with passivity would have nothing admirable about it.7

In a remarkable 1978 speech, Pope John Paul II quoted Cicero: “Non enim tam praeclarum est scire Latine, quam turpe nescire” (“It is not so much distinguished to know Latin as it is disgraceful not to know it”).8 In other words, we mustn’t be lazy about educating ourselves. We should acquire some knowledge of the principal language of Western civilization and of the Roman Church. Assuredly such knowledge does not reduce the mystery of the traditional liturgy; if anything, it intensifies one’s astonishment at its spiritual subtleties and literary allusions.9 Intellectual enrichment and cultural literacy are always that way: so far from narrowing one’s life, they multiply occasions of wonder and open new possibilities for contemplation. Beauty itself seems to grow as one’s capacity to see it or hear it grows.

Perhaps we could put it this way: the traditional Mass is good not because it baffles us or presents barriers, but because it humbles our pride and whets our appetite, with the barriers as so many provocations to intimacy. As the Lord says through the prophet Isaias: “I will give thee hidden treasures, and the concealed riches of secret places: that thou mayest know that I am the Lord Who calls thee by thy name, the God of Israel” (Is 45:3). The mystic is the one who ardently follows the truth into the fiercest thickets and fieriest trials. The Mass as the mystical re-presentation of the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross should be a place where everyday mystics are bred and fed—members of that Body we call Mystical. Against the rationalists of yesterday and today—the reformers at the Synod of Pistoia, the periti at the sacrosanct Council—let us thank God, in the aforementioned words of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, “for all things we know and do not know, for blessings manifest and hidden that have been bestowed on us.”

A concluding thought

This series bore the subtitle: “Why it is better not to understand everything immediately.” But now I would like, in conclusion, to revise that language.

On the one hand, it is impossible for us to understand everything immediately — that is a prerogative of God alone; and to the extent we are led to think we understand more than we actually do, we are being done a disservice, for knowledge and pride enjoy a subterranean link, and it is often for our good, for our humbling, that we are left in the dark.

On the other hand, it is necessary for us to come to know the two greatest mysteries with which our minds are in contact — namely, God and our own souls — slowly, lest we be blinded by the truth, overwhelmed and confused. Just as it is part of the natural order that we are fed first mother’s milk, then soft foods, then tougher foods, until we can eat nearly anything, so too it is part of the divine pedagogy in the spiritual life that, as St. Paul says in 1 Corinthians, we start on milk, and move eventually to meat.

The traditional liturgy feeds us in just this way, by starting with the milk of outward splendor — the pomp of the ceremonies, the sweetness of the music, the “smells and bells” that capture our attention and keep it focused on the external symbols — and then moving us over time to the meat of the prayers in their dense content (think of the towering mysteries of the Roman Canon!) and the subtleties of the rite that one comes to see only after years of attending it, and for the understanding of which one must put in some effort of study and mental exercise.

In short, traditionalists should challenge themselves and one another to live a life of prayer and study that fully accords with “slow liturgy,” for in this way, they will absorb its wisdom, vindicate its perfections, and extend its earthly empire, as, I am sure, we all wish to do.

See Barthe, Forest of Symbols.

de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Bk. II, sect. 1, ch. I.

Scheeben, Mysteries of Christianity, 3, 4, 6, 8, 19. The introduction to this book in its entirety (pp. 3–21) counts as one of the most outstanding texts ever written in Catholic theology.

Augustine, Confessions III.6.11: “interior intimo meo et superior summo meo.”

Spataro, In Praise of the Tridentine Mass, 30.

The phrase is taken from Gerard Manley Hopkins’s translation of St. Thomas’s hymn Adoro te devote.

Wonder is meant to lead to wisdom. My main point is that, in this life, when one engages with the sacred mysteries in their traditional home, one will never reach a plateau at which he could say: “Okay, it’s all clear now, there’s nothing left to know, nothing left to puzzle, overwhelm, challenge, or humble me.” In fact, the more we come to see, the more we will see what we do not see, and the more desire we will have for that embrace of God that will finally satisfy us and fill us beyond all imagining.

Address of His Holiness John Paul II to Participants in the “Certamen Vaticanum,” citing Brut. 37, 140.

See Foley, Lost in Translation, and Martindale, Words of the Missal.

Very weird how calling the Mass 'the sacred mysteries' has become so popular now among the novus ordo clergy when they constantly do everything in their power to desacralize and demysteriorize everything about it. Such a tragedy.

Beautiful thoughts and observations. I've often thought this is precisely the reason Christ spoke in parables -- so that we'd have to "work" at it to "find the meaning", which itself would continue to grow each time we would ponder it.