What Was It Like to Live Through the Vatican II Period? (+ roundup)

A new book of memoirs brings home the experience

Preliminaries

Please help the Tradition & Sanity community grow by forwarding this email to your friends or sharing the post on social media.

Also, if you prefer to read posts on the website instead of in email form (I do, because the website formatting is more pleasing to the eye), just click on the title of the post.

Lessons from Two Families

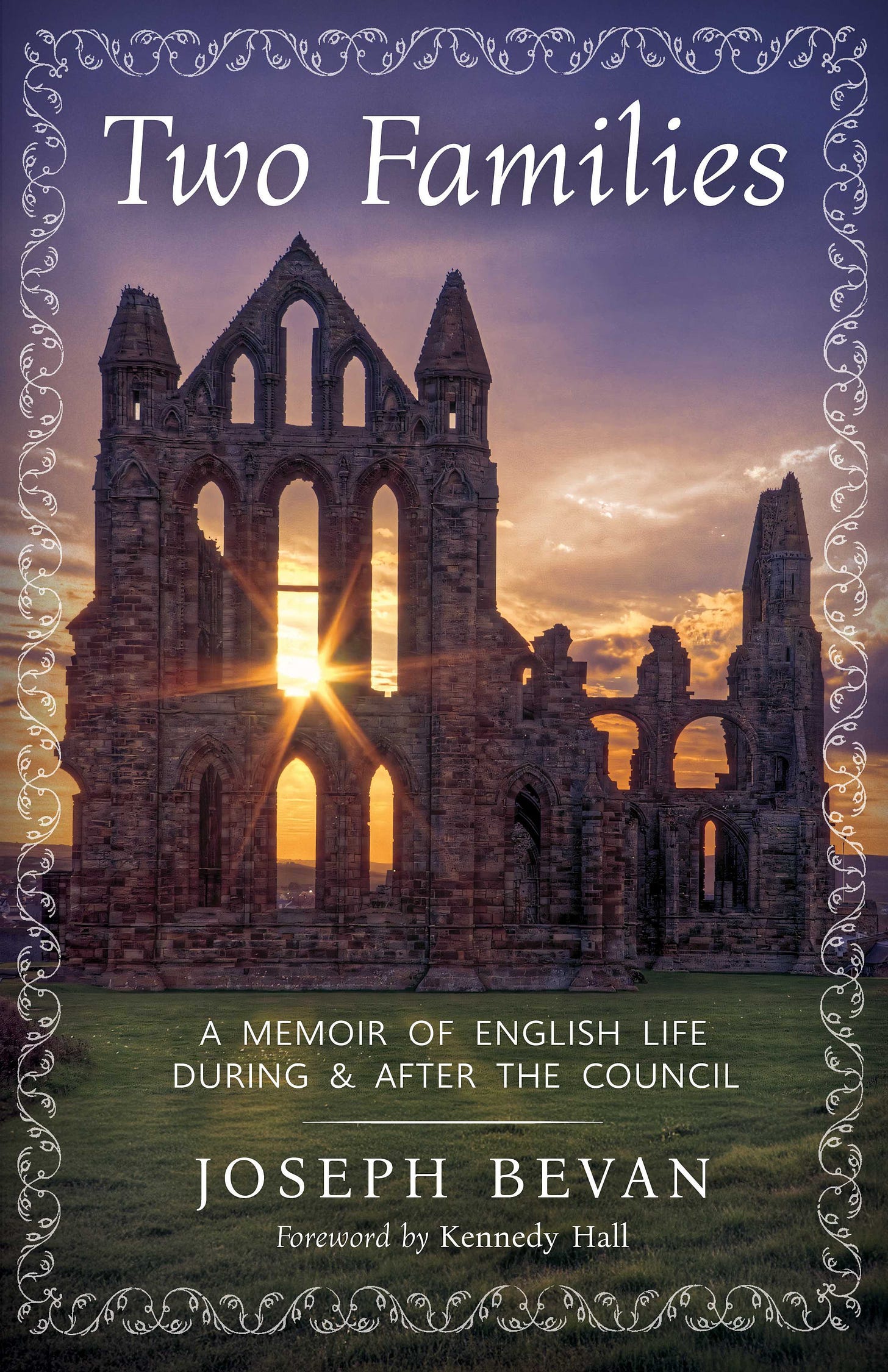

Those who move in traditional circles in the UK tell me that “everyone has heard of the Bevans.” They are a large and highly musical clan whose members have been singing for decades in liturgies and concerts. Os Justi Press is proud to have just released Joseph Bevan’s book Two Families: A Memoir of English Life During and After the Council.

To say it’s an eye-opening read would be a gross understatement. I know that some of my readers here are old enough to remember the euphoria and the catastrophes that accompanied life in the Catholic Church in the 1960s, but I would dare to say that the vast majority of readers are too young to have any memories of even the 1970s (I myself was born in 1971), and quite a few of them were born much later. I still remember the shock it gave me as a teacher when I began teaching students who had been born after the year 2000!

That is why memoirs like these are so invaluable. Bevan vividly describes what Catholic life was like before, during, and after the Council: he shows the strengths and weaknesses of the preconciliar routine, the confusion unleashed in the 1960s, the collapse of the liturgy and especially of sacred music “in real time,” as it was unfolding. Eyewitness accounts are extremely important for the history of the traditionalist movement, as they flesh out our more abstract claims with concrete examples, and help fend off accusations that we are inventing or exaggerating the problems. Those who are interested in Benedictine monasticism will learn a lot of intriguing (and sometimes disturbing) things about Downside Abbey, including the time when some students got themselves involved with demons, and one of them died on account of it.

Two Families is all the more interesting (and useful) in that it takes the form of contrasting the family into which Bevan was born with the family that he himself established later on. His family of origin was largely swept along with the tide of the times, and, as a kind of conscientious objector, Joseph Bevan and his wife decided to pursue the opposite course as they rediscovered tradition through the Society of St. Pius X and turned their lives upside-down to ensure a proper upbringing for their own large family of ten children. At a time when it was not fashionable to homeschool, they homeschooled, and later on moved to a town from which their older children could more easily get to traditional schools in France; at a time when priests were being persecuted for fidelity to tradition, they welcomed into their home an old and faithful priest. God has blessed them with two priest-sons and a daughter who is a nun.

The memoir is filled with all kinds of good, honest self-assessment of failings and opportunities, falls taken and graces received; it contains, I would say, some excellent advice for parents. Kennedy Hall contributes an entertaining and moving Foreword.

I’ll now share some excerpts to whet the appetite!

Wise words, to which we can all relate:

Although this book contains some stern criticisms of monks and priests who have crossed my path, I still regard them as belonging to my Church, and the wholesale collapse of the clergy is something I mourn. I have no idea how God is going to put things right, but I am sure that, sooner or later, he will, and it might take 100 years. In the meantime, I just carry on in my own quiet way, trying to save my soul and the souls of my nearest and dearest. (xix)

Setting the stage, with abundant good humor:

The era of my arrival into this world on the seventh of June 1957 represented an interregnum between the austerities and deprivations of the Second World War and the forthcoming throwing off of inhibitions of all kinds which commenced in the 1960s. The occasion of my birth coincided with our goat getting into difficulties and my poor mother, with labour pains, having to go into the garden to disentangle the animal from its chain. The family doctor was summoned at about 3 p.m. and, as he lived across the road, was conveniently on hand to deliver me. Doctor Carter was the father of a large Catholic family and was not only the local general practitioner but also the doctor for Downside Benedictine monastery and school, which was about fifteen minutes’ walk away. Dr Carter’s appearances at our house over the next few years precipitated a general panic amongst us younger children; we used to run and hide, having visions of injections with large rusty needles. No matter how ill we were, his advice was always, “Don’t worry, it’ll get better by itself.”

Downside Lodge, our home, was rented from Downside School by my father, who taught music there. It was a dilapidated old wreck but was sufficiently large to accommodate all of us thirteen children. It was surrounded by a large garden and lawns. I was too young for the house to make a lasting impression on me, as we moved elsewhere when I was aged seven, although I do remember the hide-and-seek games in the grounds and the gang warfare. My younger brother Jeremy was paired up with me, as we were closest in age, and my parents regarded us as inseparable. Why they should have assumed this is a complete mystery, as he was one of my most malevolent and resourceful adversaries. (1–2)

Bevan helps us to see the connection between the prevailing “permissive” culture and the self-doubting Church:

Religion was not the only thing being questioned in those days. Almost everything was. I am referring particularly to the emerging restlessness and impatience with wartime values as the whole world seemed to be on the verge of moral collapse, largely due to the arrival of efficient artificial contraception. The wholesale shedding of inhibitions was also evidenced by the arrival of industrial popular music as performed by The Beatles and others. Nothing was spared. In fact, even the Catholic Church was going through an ordeal of self-criticism and identity crisis at the Second Vatican Council, which started in 1962. In my little world, however, I was content to listen to The Beatles and chew my gum, although the prevalence of pop music in our home — an utter novelty — must have upset the tranquillity normally prevalent in a Catholic family. I think our parents tolerated the noise, but they must have wondered where their subtle loss of control would lead. There is no doubt that many Catholic families in the world were going through the same experience. I was not really aware of the so-called “permissive society” until I travelled to London for my schooling and observed public “snogging” for the first time in the streets of the capital, but I suppose the experience during my first Confession, which is described later, gave me the first clue that something wasn’t quite right. (12–13)

Ah, childhood as it used to be! (And maybe still is, among those who know what it should be…)

So much happened in my formative years, and life was so busy. I was never bored—unlike modern children—because all our entertainment was homemade. We had no television, and in any case, Ma, always frantically busy, was extremely intolerant of idleness. If I was ever caught sitting around, she would set me a string of jobs. From morning to night, I was gainfully occupied in my make-believe kingdom outside, and during the winter months I would be happily playing with my brothers and sisters in the maze of passages and cellars that were a feature of our house. (17–18)

Speaking at one point of Westminster Choir School where he attended for a short time, Bevan describes the daily routine of the choristers. This is a great passage for giving the lie to the idea that the artistic standards were not high prior to the Council. In fact, they were much, much higher than they would ever be afterwards. Even now, we have not quite caught up to “the way things were,” and I doubt we ever shall until there is a complete restoration of tradition.

The choir school supplied the sopranos and altos for the cathedral choir. Even in the 1960s it was being proclaimed as one of the best choirs in Europe, and its schedule was punishing. There was a Sung Mass every morning, and new music had to be prepared to a professional standard. We would rise early and have a school Low Mass in the crypt of the cathedral. After breakfast there would be lessons followed by sung Mass but, as a probationer, I was too young to sing in the choir, so we juniors sat in the front two rows in the nave….

The cathedral choir sound was utterly unique and a total contrast to the politeness of its Anglican cathedral rivals. We had daily High Mass in the cathedral. Even with my disturbed brain, I could see how beautiful and solemn was the drama being played out before my eyes— all accompanied by music which was often sublime. My musical tastes were maturing rapidly, and I was transported by Victoria and Palestrina….

It was a rare privilege as a youngster to witness daily the dignity and the beauty of the liturgy at the cathedral, which managed to cling to the traditional rite of Mass well into the 1970s, until the death of Cardinal Heenan. Once the glories of Catholic worship have been seen at first hand, one cannot fail to be unimpressed by the sterile and turgid offerings of the reformed liturgies in the Catholic Church following on from the Second Vatican Council, known as Vatican II. I happen to know that anyone who sang in that choir was probably marked for life, as I was, and many ex-choristers still keep in touch with each other and often meet up to sing. The old cathedral is affectionately referred to as “the drome,” but nowadays the previously grand liturgy has degenerated into a patchy concert of words and music. My three elder brothers, who attended the school at Westminster, spent their lives campaigning for proper music to be incorporated into the New Mass and have found the going extremely bumpy in the face of reluctant clergy up and down the country….

The lasting benefits of the choir school on my life were a love of the liturgy and a love of prayer. I learned to pray, and this stayed with me even during my non-churchgoing period. I never completely lost touch with Our Lady and the Saints, and this saved me from disaster, I think. (24–27)

There was a lot of confusion, silliness, and Pelagianism in the shift from the old rite to the new rite:

We [the Bevans] were the official choir at St Michael’s Church in Shepton Mallet, and every Sunday in the holidays we sang the Mass. My father was the conductor and organist, and he laid out treats for the congregation in the form of plainchant and polyphony. With the closing of the old Catholic church in Shepton we moved to a spick-and-span affair of concrete and glass, which had been built by the diocese to accommodate the new springtime in the Church anticipated by the recent Second Vatican Council. With the new building came the New Mass. I was first made aware that something wasn’t right when, during the Canon, I received a dig in the back from Neville Dyke, who was sitting just behind me. I turned round in surprise and said, “Hello, Neville!” I received the reply, “Peace be with you!” I answered, “Talk to you later.” I can still see the Catholic families of Shepton Mallet sitting in their habitual pews: the Tullys, the Dykes, the Quins, the Dampiers, the Todds, and many others with lots of young children. With the advent of the New Mass in December 1969, the services became chaotic. The parish priest, Father Carol, wrestled with the new liturgy; he would suddenly break into Latin and correct himself.

The music we sang as a family in church was becoming irrelevant to the goings-on at the altar, and the congregation became restless for more change. Mrs Todd, the wife of the owner of Darton, Longman & Todd, which was a leading Catholic publisher, became an agitator for change in the music. One Sunday, as we struck up with some William Byrd, she simply marched out of Mass in full view of the whole congregation.

Pa, like the Elizabethan composers before him, adapted to the demand for change and started writing “congregational Masses” to be sung by everybody at Mass. I have to say that these compositions were so trite and turgid that we got thoroughly bored with them. In actual fact, Mass on Sunday became a frightful bore with its “sweet nothings” prayers, “hello children everywhere” readings, and faulty microphones. It took a great personal effort to rise on Sunday morning and go to church. As it dawned on our new parish priest, Father Meehan, that the reformed liturgy was turning out to be a bit of a flop, he decided upon a more “energetic” approach to the liturgy. As a result, we were made to endure all kinds of humiliating displays, such as parading the children in the sanctuary and the priest quizzing them over the microphone.

We all hated it, but Pa said, “If you live at home you go to church!” I think Pa liked the changes. In fact, he did say in an unguarded moment— following a session with the gin and martini bottles— that it was like coming home to his Church of England past. Ma endured the revolution patiently and, much later, embraced Catholic Tradition again.

In those days we were witnessing the changes in the Mass, which were bad enough. Little did we know that there was a wholesale offensive against the Catholic faith going on at the highest levels, and the New Mass was just a symptom of this attack. My mother has testified to the gradual meltdown in Catholic moral theology amongst her own teenage daughters, who were only following the example of their friends. (33–35)

I could keep quoting Bevan, but that would spoil the pleasure of discovering the twists and turns for yourself! So I’ll stop here, but do consider reading this meaty but still compact (under 200 pages) memoir of a Catholic caught between a false modernization that failed to fulfill its promises and a return to tradition that actually delivers the goods—the interesting story of a man, typical of his era in many ways, who was led by grace from lazy lapsation to burning zeal for the Faith.

Two Families has received glowing endorsements from an impressive array of readers:

The Right Reverend Dom Cuthbert Brogan, OSB, Abbot of St. Michael’s Abbey, Farnborough: “Joseph Bevan traces this family’s voyage through the choppy waters of Church life in England in the last decades. In recalling these years, the author chronicles the collapse of the liturgy and of religious life, and gives examples of decadence in Church music and the effect this had on the practice of the Faith for himself and his family. Frank about his own shortcomings and realistic about the current crises in the Church, Joseph seeks a solution to modern ills. He finds this in a renewed immersion in Catholic tradition, doctrine, and practice. Two Families is an engaging and honest work.”

Dom Alcuin Reid, OSB, Prior of Monastère Saint-Benoît, Fréjus-Toulon: “This is an inspiring book that grittily teaches a perennial truth which we ignore at our peril: genuine charity is ‘the only defence’ against all that assails us. Whatever our state in life, Two Families challenges us to return to its daily practice whilst there is still time.”

Edward Pentin, Senior Contributor, National Catholic Register: “Wise, amusing, and beautifully written, Bevan shares not only the secrets to a well-lived Catholic life that has borne abundant good fruit, but also invaluable insights into the extent of the crisis facing the Church. Recalling the ups and downs he and his wife Clare faced in raising ten children as the post-conciliar Church steadily imploded, Bevan is candid and incisive in his analysis, offering much-needed hope and guidance not only to Catholic families but to all Catholics serious about their faith.”

James Bogle, barrister, retired army officer, former President of the Una Voce Federation: “The Bevan family are well known throughout his native Somerset and, indeed, in England and internationally, for their musical talent as a family choir. Joseph’s lifelong career in church music has given him an insider’s perspective on the liturgical revolution that took place after the Second Vatican Council. A mixture of nostalgia and realism, historical charm and contemporary comment, the story carries the reader along whilst providing insight into a most unusual time in the history of two families, a country, a Church, and a world.”

Anthony P. Stine, Return to Tradition Podcast: “These memoirs by Mr Joseph Bevan remind faithful Catholics that the only certain means of preserving the faith today is to follow what we must unfortunately call ‘Traditional Catholicism’ (as if any other kind should exist!), which begins with the traditional family.”

Available directly from the publisher in paperback, hardcover, or ebook, as well as from Amazon.

Trip to Maine

Last weekend’s visit to Maine, for a nephew’s wedding and a lecture in Falmouth, was truly a lovely time. I met a Facebook friend in person for coffee in Bath on a foggy Saturday morning, and prior to our meeting, walked around the largely empty town.

Sunday morning saw me at the Basilica of SS. Peter & Paul in Lewiston, home of a longstanding Latin Mass. French-speaking Dominicans from Canada built this church long ago, as one can tell from the French of the Stations, and the Dominican shield at the back of the sanctuary.

There was a great turnout for the talk in Falmouth and the dinner afterwards. Books flew off the table. Catholics are hungry for the truth! One of the highlights was seeing all the youngsters in the audience. I don’t think I’ve ever had so many teenagers at a talk, and they were all paying attention!

The trip ended with a delightful (and all-too-short) visit with Phil and Leila Marie Lawler at their elegant 1860 home, just before I did my weekly penance by going to Logan airport.

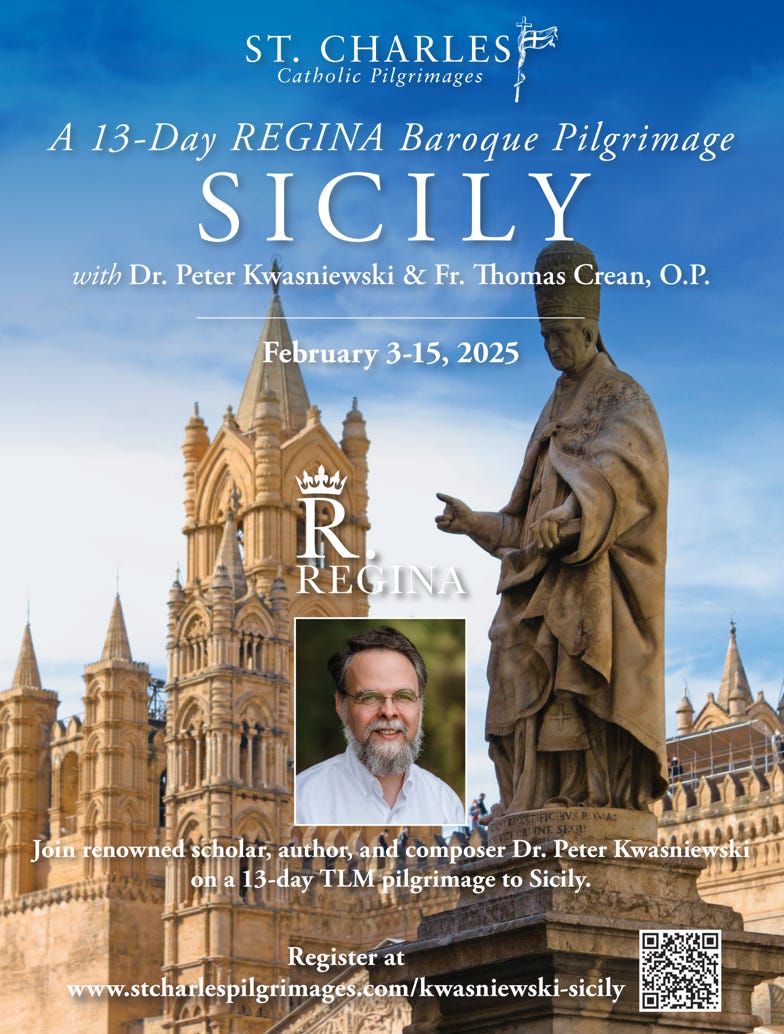

Sicily pilgrimage

We still have a few places left for the February 2025 pilgrimage to Sicily, on which I will be the special guest and co-leader, and Fr Thomas Crean will be our TLM chaplain for daily Mass. As you can read about here (accompanied with lots of pictures!), our itinerary is outstanding for both religious and artistic reasons. Most people do not appreciate just how rich in Catholic culture Sicily is; as I’ve mentioned elsewhere, Dietrich von Hildebrand, that great philosopher of beauty, always made a point of taking his students to this island.

Prize for best article

I am thinking of awarding this “prize” each week. The winner is usually quite obvious, as it will be an article or essay that towers above everything else.

Remember the outstanding exposé of Bergoglian theology and strategy written by one “Vigilius” and published last month at Rorate under the title “The Great Loss: Or, the Pontificate of Jorge Bergoglio”? Well, Vigilius is back and better than ever, with a sequel: “Is Jorge Bergoglio a Strategist? A Reply to Caminante-Wanderer.” Anyone with the slightest interest in understanding this chaotic and maddening pontificate will certainly benefit from the clarity it brings. As the author states at one point:

The extent to which the Bergoglian pontificate is of a strategic nature can be seen in the systematic linkage of the various theological topics. The Synod on the Family with Amoris laetitia, the Amazon Synod, the Synod on Synodality, the Abu Dhabi Declaration, Evangelii gaudium, Fratelli tutti, Laudato si, Laudate Deum, Fiducia supplicans are by no means mere individual events, but coordinated moments in the program for the comprehensive implementation of the central Bergoglian ideology.

Other articles I’ve enjoyed recently

At The WM Review, “On the immorality of labelling other Catholics as ‘radical traditionalists’.”

Caveat lector: The WM Review is a sedevacantist publication, but it provides access to good resources, especially translations of hitherto unavailable theological documents. My recommending the above article therefore gives me occasion to mention that there appeared simultaneously two pairs of articles, one by Matthew McCusker at LifeSite (1, 2), the other by Matt Gaspers at OnePeterFive (1, 2), arguing precisely contrary theses. McCusker argues that Francis cannot be pope, and makes the very tightest case you will find anywhere for this conclusion. Gaspers argues that even if Francis was fraudulently elected and even if he is a heretic, he is still the pope at this time, “quoad nos” (as far as members of the Church are concerned). In my opinion, Gaspers wins this “debate” (as I said, they were not addressing each other).

Over at Rorate Caeli, there’s a quite interesting, though rather densely written, reflection by a Polish professor. Part 1 is called “The World of the Dead and Childless Wives: A Philosopher of Religion on the Logos, Tradition, and Demographics.” Part 2 is called “How the Loss of Children and the Demographic Collapse Are Linked to the Loss of Tradition.” A taste:

The attitude of “re-enactment”...consists, as Marrou elaborated on the basis of Herodotus and Thucydides, in rediscovering the ancient units of meaning, axiologai. Axiologai are what is used to bring answers to the questions of all human being: What is there in life to be desired? What to live for? What to die for and how? Re-enactment is the mechanism of tradition. It goes from the dead, through the elder living, through the young living, to those who are expected (if they are expected). If there are no children, there can be no re-enactment (in this world, at least)....

On this axis of time, the deposit developed by past generations is passed on, including what they consider their particular treasure: usually religion and the model of piety, the developed model of political community and the sacrifice of life and work associated with it. Also family history and family memorabilia. What is passed down is defined by the Latin term “traditio,” tradition. So who is this homo temporalis who understands that he is also homo historicus, and who therefore constantly strives for re-enactment? As it turns out, he is a traditionalist.

An important medical study was released that should (but probably won’t) stop people from viewing the so-called “vegetative state” as an excuse to pull the plug: “Study: People in Vegetative State May Be Aware and Thinking.”

Phillip Campbell issues a much-needed reminder to all of us (and especially to trads, who have many reasons, or at least excuses, to be ornery): we should be at our best, our kindest, in our practice of religion.

Robert Keim, in “An Art Which Leads the Soul by Words”: Sacred Rhetoric in the Roman Liturgy, explores a truth that tends to be sorely neglected:

Christian culture is so interwoven with rhetoric that the two are actually inseparable: Old Testament literature is filled with rhetorical techniques, Our Lord integrated rhetoric into His preaching, the epistolary style of St. Paul—recently described by a biblical scholar as “one of the greatest communicators in history”—was enriched by his rhetorical skill, and the Church’s ancient liturgies employed highly rhetorical texts. Indeed, rhetoric is so central to salvation history and the Christian experience that a new definition is called for, one that pertains specifically to Christian education and foregrounds the role of rhetoric in the spiritual and liturgical life of the Church. I will propose one: rhetoric is the sublimation of language.... Rhetoric comes not from Greece or Rome but from God. He not only created language but also taught mankind to use it dramatically and artistically, so that literature and preaching and conversation and all other forms of human discourse might fulfill their crucial and exalted role in His epic plan to ennoble our lives and save our souls.

Pius Assumptions

Pius XII’s creation of a new proper Mass for the Assumption is a particularly good example of the needless flexing of papal muscles. Why would a centuries-old liturgy for the day of the Assumption need to be retired, thus rendering out-of-date reams of educated commentary thereupon, and a new one put in its place? The Gospel of SS. Martha and Mary was traditionally read for good reason, as Gregory DiPippo explains in a fine article. Changing the Mass of the day could imply, to some observers, that the dogmatic decree was an abrupt change in what Catholics believe (lex orandi, lex credendi), whereas retaining the same Mass would show that the newly declared dogma was nothing more than a making explicit of what had always been believed. Such considerations seem to be foreign to the mind of the modern authoritarian papacy.

Approved by the Roger Scruton Committee for Classical Architecture

I just made that up, but if there were such a thing, it would approve this video.

In the opposite corner stands the FSSP’s grand (and long-needed) new parish church in Phoenix — one of the most impressive and ambitious architectural projects yet undertaken by a Fraternity apostolate. It would be a worthy object of tithing! Read more about it here.

Julian’s Corner

For those who are interested in following the work of Tradition & Sanity’s co-author on other platforms:

“Prayer Is a First Resort”: An Interview with Fr. Benedict Kiely

New Catholic trade school launches in Illinois [interview with Dr. Kent Lasnoski about the San Damiano College for the Trades]

The Biological Adventure Clock [about Antoine de Saint-Exupéry]

Reminder…

If you’ve read this far, and benefited from the roundup, please consider taking out a paid subscription, or if you’ve already done that, consider giving a gift subscription to another or dropping a tip in the tip jar. Making a living as a writer is fulfilling and at times just a bit uncertain, so your help enables this Substack to go strongly into the future, come what may.

Thank you for reading, and may God bless you!

Boys Catholic High School retreat circa 1970-71...black lights, psychedelic posters, group sessions. It was more about 'getting to know yourself' than getting to know Jesus. How's this for an occasion of sin...they invited a girl's Catholic High School at the same time and thought it would be a good idea to match up boy/girl and spend a few hours 'getting to know your partner'. Then afterward we sat around in groups to let everyone know what we found out about each other lol.

Another great Friday post full of thought-provoking topics. First: what was it like to live through Vatican II? Horrible. I literally ran away from the church as a freshman in high school, so shocked and turned off by the overnight introduction of banality and the falsity of it all. It was no longer my church and I felt Jesus had run away too. Fortunately, I came back much later. I look forward to reading this book to see how others fared. Every experience was different but with basic underlying similarities, I think. Also watched the architecture video. So on target and so true. It's another cultural aspect we don't necessarily think of affecting society to the degree she mentions, but when she showed the photo of the soaring interior of a medieval church (after showing photos of Bauhaus and current architect), I felt my stomach relaxing and my heart sighing with relief. Wow, we are truly a very sick society.