What We Learn from Monasteries—and What It Means to Be a Benedictine Oblate

Two important liturgical dates are associated with the patron of Western monasticism and co-patron of Europe. The traditional Roman calendar observes his feast on his transitus, or passing into eternal life, on March 21. The modern calendar of Paul VI observes his feast on July 11, the date of the translation of his relics. Benedictine monks and nuns customarily celebrated both feasts, which even had octaves — the more festivity, the better!

The first time I read the Rule of St. Benedict as a young adult, I found it stiff and dry. In reality, I was not yet ready for the purity and depth of its wisdom. Many years passed before I read it again — and this time, my reaction was quite different.

The Prologue in and of itself struck me as one of the most profound summaries of the Christian spiritual life I had ever seen. The chapters on humility, on the instruments of good works, on the manner of praying the office… these made me realize that I was standing in the presence of a lawgiver like Moses (to whom indeed the traditional liturgy compares the Holy Patriarch!). That Christian Europe, the heart of Christendom, had been constructed primarily by Benedictines ceased to surprise me.

Although I had known or seen Benedictines before, it wasn’t until my visits to the monastery of Norcia that I felt as if I had encountered monks who truly lived by the spirit and letter of the Rule. Their enthusiasm for divine worship (the opus Dei or “work of God,” as the Rule calls it), their quiet joy, and their example of simple fraternity and sincere hospitality drew me back again and again.

Visits to the monasteries of Le Barroux, Silverstream, and Clear Creek only increased my love for Benedictine monasticism. After praying about it, I decided to become a Benedictine oblate of Norcia, where I made my final oblation on May 22, 2014, the feast of St. Rita of nearby Cascia. Ten years ago already! Since then I have made many trips back to Norcia and several also to the Benedictines of Mary in Gower, Missouri (about whom I’ve written here, here, and here).

What are some of the lessons one learns from monks or nuns by visiting them and spending time among them?

God has pride of place. The horarium — that is, the daily fixed round of prayer — takes priority over everything else. If a monk is doing some job and the bell rings, he has to wrap up what he’s doing, or leave it unfinished, and go back to the chapel. If you are expecting to meet a certain monk to talk about some personal or professional matter, you have to wait your turn; it could take days to see the person you want to see, because they are so busy with the “work of God” — that is, the round of prayer. Your own needs are in third place; first comes worship, then the immediate needs of the community, and finally — as time permits — your own. It is exactly the opposite of the modern world’s motto, “me, myself, and I.”

God deserves our best. Out in the world, there can often be a hasty and slipshod approach to serving God. We do what’s convenient for us. We make things snappy because we have “stuff to do.” Human work tends to take precedence over divine work, the active life over the contemplative. While monks face the same temptations to activism, anthropocentrism, and cutting corners as all other fallen men face, their life has been designed “from the ground up” to be theocentric, receptive, and maximalist. Authentic monks give their first and best hours of the day to God. They give Him the most splendid liturgy they can offer. They strive to store up riches in Heaven rather than on Earth. Their life exists for worship and they act like it. “Let nothing be preferred to the work of God,” says the Rule.

God is the meaning of our life and everything in it. In the world, we tend to compartmentalize: I’ll give this weekly hour or two to God, but the rest of the week is for me and my sphere of concerns. We buy and sell, give and take, wake and sleep, eat and drink and recreate, often without a thought for life eternal, without the infusion of prayer that should permeate our life like incense in a church.

The monks, on the other hand, have set up their lives so that everything they do, wear, eat, or say is rooted in God and flows back to Him. This happens not only in the liturgy, where it is most obvious, but also in the routines of the refectory, in the sacral silence of the library, in their recreations and walks, in the friendly conversations in guesthouse or bookshop. A good monastery’s residents, buildings, and activities will persistently remind visitors that “God is all in all” (cf. 1 Cor. 15:28) and that “we have here no lasting city but seek one that is to come” (Heb. 13:14).

This is not to say that any monastery or any monk is perfect, but rather that, at its best, the monastic life supernaturalizes all of human life, orienting it toward its transcendent destiny. As Fr. Louis Bouyer taught in his superlative book The Meaning of the Monastic Life, the monk or nun strives to live with maximum consistency what every Christian vows to be in baptism: dead to sin and risen with Christ in the heavenly places — without any habits of compromise, freed from even legitimate worldly pursuits.

God is real, and we encounter Him. In the world, thanks to our forgetfulness and hardness of heart, God seems distant, vague, unreal, more of a concept than a certainty. The solution to this disconnect between ourselves, who have such a tenuous purchase on reality, and the One who is in fact the most real and the source of all reality is not an evangelizing big-tent Christian rock concert or a gooey “sharing” of life stories. We meet this God in the calming repetition of the Psalms He gave to us; we meet Him in the silence that compels us to go beneath the surface and beyond the conventional; we meet Him in the serious joy or joyful seriousness that radiates from men who have given all to Him that they can give.

There is no joy like this to be found in the madding crowd. The world is a hard master that demands everything and gives, ultimately, nothing but emptiness and regrets. Pleasures run out quickly, demanding frantically to be renewed: a despair lurks at the center of them. The monastery demands everything and gives more than everything. It connects all that is noble and all that is humble in a man’s life to the One who gives reality its reality, who endows our thoughts, words, and actions with meaning.

Hospitality as a way of life. Fallen human beings — especially in the Modern Age, which pushes hard the errors, only apparently opposed, of individualism and collectivism — are burdened with a tendency to “curve inwards,” as the medieval theologians put it. We take stock to make sure we are and will be well fed; when we share, it is with difficulty or for enlightened self-interest.

St. Benedict’s Rule embodies the opposite attitude: food is for sharing with guests, prayer is for the benefit of all, the liturgy is a gift free and fertile beyond measure, life is to be expended not on oneself, but in service to brethren and strangers. The kernel of civilization is the Rule in its famous principle of hospitality: every guest, be he mighty or marginal in the eyes of the world, is to be received as Christ. Moderns treat even their own children as strangers; monks treat the stranger as Christ. This is the difference between a culture of death and a culture of life. An observant monastery brings the difference vividly to light.

Visiting a good monastery is always a challenge and a consolation. On the one hand, it shows us how little we are actually giving to God of what we could give to Him; it points up our lack of generosity, our inconsistency and inconstancy, our petty pleasures and disorganized priorities. On the other hand, it reminds us that God is greater than our problems, that His grace is sufficient for our weakness, and that He is calling us gently but insistently to embrace more self-discipline and self-denial for the sake of a fuller life in Him.

On Being an Oblate

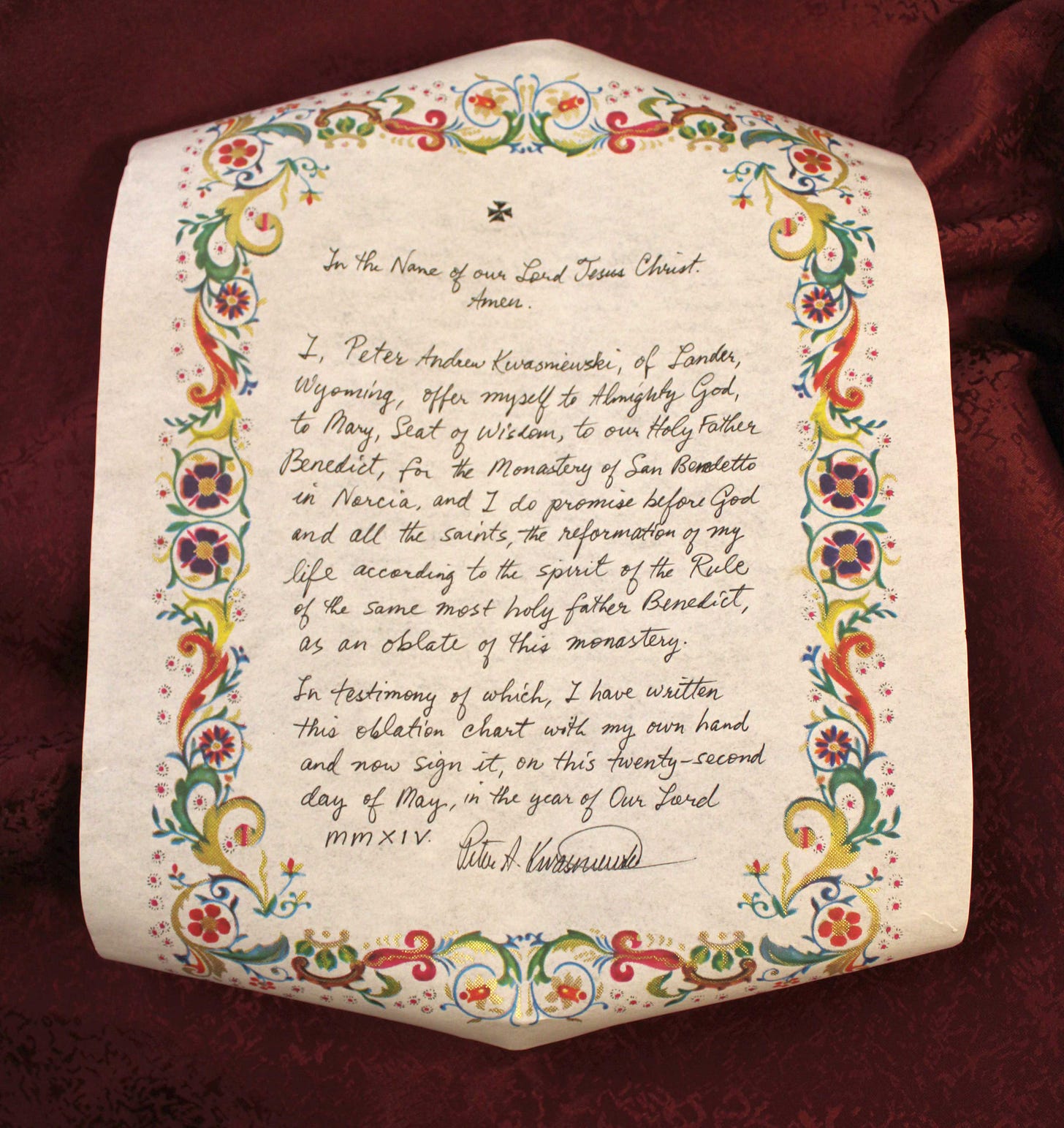

As mentioned above, I became an oblate of the Monastero di San Benedetto — now, the Abbey of San Benedetto in Monte — on May 22, 2014. Immediately after Vespers that day, Fr. Cassian Folsom, then-Prior of the community, received me as an oblate in the presence of the other monks. The ceremony was short, solemn, and beautiful, culminating in the reading of the hand-written oblate chart, the signing of it upon the altar, and the chanting of the “Suscipe” together with all the monks:

This, of course, was in the old basilica that the earthquake of August 24, 2016, obliterated, as it did so much of the town of Norcia — precipitating a “flight to the hills” where the monks have built a bigger and better monastery for themselves, exemplifying one of the many unofficial mottoes of the Benedictine Order: succisa virescit, cut down, it grows back stronger.

Over the years, many people — some out of simple curiosity, others from an openness to discerning the same call — have asked me what exactly it means to be an oblate.

To put it simply, an oblate is someone who “offers” himself (oblatio = an offering) more fully to God in the context of a particular monastic community and under the guidance of the Rule of St. Benedict, duly adapted to the life of a layman. Historically, some oblates have lived in or near the monastery in question, but that is not absolutely necessary (although it would be exceedingly wonderful and perhaps someday the good Lord will make it possible for me!). What matters most is that the oblate strives to share in the spiritual goods and discipline of the monks (or nuns — I am always writing with them in mind too) by embracing something of their way of life, praying for them, and benefiting from their prayers. Where the Lord has provided the means, an oblate will also support the community in its material needs. When you read the annals of European history, you realize that royal and aristocratic patronage of the monasteries, often by individuals living as oblates or related to community members, was a key reason they could flourish as they did throughout the countryside.

Oblates have a long history in Benedictine monasticism, much longer than the “tertiaries” or “Third Orders” that are more familiar from the later Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites, and other medieval or post-medieval orders. (Benedictines like to say these are the “latecomers” in Church history… we’ve been around since the sixth century, and of course monasticism goes back several centuries before that.) The concept is, however, similar: as a Dominican tertiary lives out his baptismal vocation within the context of Dominican spirituality and guided by Dominicans past and present, so a Benedictine oblate lives out his baptismal vocation in a Benedictine spirit, with occasional retreats at his “home monastery” and, often enough, with advice from a monastic spiritual guide or spiritual director.

Since God draws souls with great freedom and delicacy, and for all sorts of reasons, I hesitate to speak of a telltale sign of when one should consider becoming an oblate. But this much seems obvious: if you relish the writings of monastic authors (e.g., among older authors, St. Gregory the Great, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Guigo the Carthusian, St. Hildegard of Bingen, St. Gertrude the Great, or St. Anselm of Canterbury; among more recent authors, Dom Prosper Guéranger, Dom Hubert van Zeller, Bd. Columba Marmion); if you love praying the Psalms in the Divine Office and, more generally, if you find the liturgy to be the primary reference-point for your spiritual life; if a visit you made to a monastery proved to be a highlight in your life as a Catholic and something you look forward to doing again, or perhaps do on a regular basis — all these would be reliable indications that a closer association is worth looking into and praying about.

Becoming an oblate was just the right step for me, to formalize what I was already trying to do in my spiritual life as a traditional Catholic. Here is the essence of it, as understood by nearly all who write about oblate life.

1. It is a “vocation within a vocation.” Whatever one’s calling or state in life is — whether one is a married person, a single person, a widow or widower, a priest or deacon — as an oblate, one strives to live it better with the help of monastic spiritual practices and the support of the prayers of one’s extended monastic family. One prays in turn for the monks, who, being on the front lines of spiritual combat, need the support of our prayers.

2. Each day, one prays some portion of the Divine Office. This could be Lauds or Prime, Vespers or Compline, the little hours, even Matins for the ambitious — whatever and however much fits into one’s schedule. A layman is not “bound” to it in the same way as a monk is; he promises to offer it as a free-will offering. The promise should be kept, but it is not considered an obligation that “binds under pain of sin.”

(A priest, who is already bound to recite the office, still gains from being an oblate, however, since he is now united in a special bond of prayer with the monks who are his spiritual family; and especially nowadays, a priest who wishes to pray a traditional form of the Divine Office may find the monastic one well-suited to that purpose. Among its many virtues, the monastic office can boast that it has remained essentially unchanged since St. Benedict laid it out in the sixth century — unlike the Roman breviary, which was severely altered by Pope Pius X early in the twentieth century.)

An oblate may use either the Monastic Office, the Roman Breviary, or the Liturgy of the Hours, though I would recommend using the first of these, as it brings one more closely into harmony with the prayer of the monks of the monastery to which one belongs. Prime and Compline take about 10 minutes each if one recites them. Lauds or Vespers would take more like 15-20 minutes for recitation. Some oblates pray these hours aloud with other members of their families. One should, however, be cautious about imposing any of the Office on other members of the family unless they truly wish to take part, as too much regimentation or expansion of a vocal prayer commitment can backfire.

3. Each day, one reads a small portion of the Rule — available in editions that, like this portable one, conveniently divide the text into one or a few paragraphs per day — and one does some lectio divina or prayerful reading of Scripture. Again, this can occupy just a few minutes, or it can be longer, depending on one’s schedule.

The point of the daily routine is to ground a person in these rich, objective, traditional practices that have a stabilizing and sanctifying effect, as testified by the thousands of canonized and beatified Benedictine monks and nuns. The Order of St. Benedict has, in fact, more saints than any other order — and it is not simply because they have been around the longest! Certainly I can testify that my life is fortified by the strong presence of St. Benedict and his Rule, always pointing me in the right direction.

The foregoing is only a sketch. Most monasteries have something like “Oblate Statutes” that spell out what is required and expected of an oblate. Typically, a monastery asks that those who wish to be oblates should first visit the monastery and spend some days there.

The next question that arises is, how important is it to be connected to a community that is nearby (or at least easily accessible by car)? Or to put it negatively, how great a disadvantage is it to be far away from one’s home monastery? This question inevitably arises because, especially in the period since the Second Vatican Council, religious life in general — and Benedictine monasticism in particular — has suffered grievous blows: there are just not that many vibrant Rule-abiding monasteries left, particularly if one is looking for the traditional Catholic liturgy to boot. The monasteries that would be worth considering might well be hours away by car or even by airplane, as in the case of my home community, which is located in the province of Umbria, Italy.

One can, nevertheless, be a Benedictine oblate of any monastery, even if it is across the world. There are obvious benefits to being able to visit a monastery at least once a year, and this is why American traditionalists have tended to choose affiliation with Clear Creek or Gower. In any case, for the dozen years I lived in Wyoming, Oklahoma was about as hard to get to as Norcia — and in off hours I’d rather be eating wild boar, truffles, and gelato. Joking aside, I have longstanding friendships in Norcia from the years I lived in Europe that made that community the right choice for me.

Plus, there is the subtle but important question of the “spirit” of a given community. Unlike the Dominicans or Franciscans, who broadly speaking are one family, each Benedictine monastery is an “autonomous” community, like a family in its own right, and as families differ a lot, so do monasteries. Some are colossally invested in divine worship, while others are less grandiose (this difference already existed in the Middle Ages—one need only compare Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis and St. Bernard of Clairvaux); some are intent on physical and manual labor, others make more of a place for intellectual and cultural pursuits; some offer spiritual direction, while others are “hands off” when it comes to oblates. Also, the manner in which hospitality is exercised can vary quite a bit.

In the end, the only way to know if you should become an oblate and if this or that particular monastery is the place to seek affiliation is to visit the place and see firsthand how it goes, how it works out. Visit more than one if you can. There’s no rush; let God speak to you in His good time. If you are meant to become an oblate, He will tug at your heart about it.

Recommended further reading

Canon G.A. Simon, Commentary for Benedictine Oblates on the Rule of St. Benedict

William Fahey, ed., The Foundations of Western Monasticism (this book contains three classics: St. Athanasius’s Life of St. Antony, the Rule of St. Benedict, and St. Bernard’s Twelve Degrees of Humility and Pride)

Dom Columba Marmion, Christ the Ideal of the Monk

Fr. Louis Bouyer, The Meaning of the Monastic Life

Fr. Dwight Longenecker, Listen My Son: St. Benedict for Fathers and St. Benedict and St. Thérèse: The Little Rule and the Little Way

Dom Pius Mary Noonan, OSB, The Grace to Desire It: Meditations on St Benedict's Twelve Degrees of Humility

“St. Benedict’s Rule embodies the opposite attitude: food is for sharing with guests, prayer is for the benefit of all, the liturgy is a gift free and fertile beyond measure, life is to be expended not on oneself, but in service to brethren and strangers.”

Thank you for a wonderful article, Peter. I’ve been an Oblate almost 40 years, and as wife and mother the hospitality was where most of the energy went (though with plenty of prayer and study, of course). Now as a widow with an empty nest, I am far more devoted to the Liturgy, which (as you say) is “fertile beyond measure.” The beauty of praying in communion with the Church (and the faithful Benedictine communities in particular) is such a consolation. Their humble dedication to “ora et labora” worked wonders over the centuries and is needed now more than ever.

As for your titles at the end, I cannot recommend Canon Simon’s “Commentary” highly enough; and of course any work by Dom Marmion is a treasure. Happy feast day!

Thank you, sir, for this interesting article! I am a former member of the Secular Franciscan Order, but left them when their “woke” tendencies became evermore intolerable: to me, at least. I feel a kinship with St. Francis of Assisi still, having studied his life and writings for a long time. Another, more traditionally-minded, Franciscan organization has piqued my interest, but I’ve felt a bit “gun-shy” about committing to them due to my previous experience. Your article about your serious commitment to a Benedictine vocation within a vocation has, well, steeled the seriousness of applying myself to such a vocation, albeit a Franciscan one! I don’t know if that’s considered ironic or not, but the article has helped me with the decision. I’m grateful.