Why Catholics Should Learn to Dance

Three authors—Dr. Kwasniewski, Dorothy Cummings McLean, and Julian Kwasniewski—respond to "traditionalist" arguments against dancing

We are pleased to welcome today to our Substack a guest writer, Dorothy Cummings McLean, who, together with Julian and me, will address a topic of some importance in traditional circles: the positive good of holding dances for Catholics of all ages, including unmarried young people. As a ballroom dance organizer who blogs at “Mrs. McLean’s Waltzing Party,” Dorothy is certainly well qualified to share her thoughts. (Whatever you do, make sure you read all the way to the end. You won’t want to miss Julian’s devastating refutation of our modern-day Jansenists!)

I’d like to set the stage by sharing some personal reminiscences and thoughts.

A Healthy, Normal Social Recreation

by Peter Kwasniewski

For full disclosure, I am not myself a talented dancer, nor have I kept it up over the years. I did, however, dance enthusiastically in the first half of the 1990s at Thomas Aquinas College, which is where I first encountered the concept and reality of real dances — by which I mean, not the random gyrations and freeform calisthenics of nightclubs, mosh pits, and other places of dubious repute, but the kind of stylish, elegant formal dances known to all civilized peoples in every age of the world prior to ours: country dances, line dances, waltzes, the Ländler, and even the swing, which is energetic and looser, but still social in character (not individualistic) and patterned (not freeform).

These TAC dances sharply contrasted with the only “dances” I’d known before, namely, the pathetic high school get-togethers in which everyone felt hyper-self-conscious, no one dressed well, no one had good manners, and kids seemed bent on lust like zombies on flesh. At college, the dances were an occasion for all the students to dress up spiffily and be on their best behavior. The class in charge of putting on the dance spent a day or more decorating and preparing for the event. Sometimes there was live music, and the playlists were quite decent — think Strauss waltzes, Benny Goodman, the Virginia Reel, and the Ländler from The Sound of Music.1

What struck me back then was how good, wholesome, innocent, and healthy these TAC dances were. So far from being wild, lascivious, and immodest, they were exhibitions of good taste, social restraint, a “safe environment” (as we’d say nowadays) for getting to know members of the opposite sex, and plenty of harmless fun and physical exercise, which is exactly what young adults need from time to time in order not to be excessively burdened with the usual cares of life. Or even just as a way to get off of computers and phones for a little while (that wasn’t so much of a problem in the early 90s, but it sure is today.)

When we started up Wyoming Catholic College in the fall of 2007, the four annual dances — each put on by a different class — took their point of departure not so much from the legendary formal balls of the Integrated Humanities Program (IHP) at the University of Kansas as from the continuous traditions of the semi-formal dances held at Thomas Aquinas College and Christendom College.2 I’d say the WCC dances boasted the same positive qualities I mentioned above.3

In our required junior-year music course at WCC, we read a most remarkable essay by educator Michael Platt, entitled “A Different Drummer.” Happily, the text is online and I’d urge you to read it. He develops at length the argument that the good or bad moral character of music is revealed most directly in how people typically dance to it.4

There’s a lot more I could say, but I’d like to get straight to the main point. In recent years, I’ve noticed a disturbing trend in traditional Catholic circles: vitriolic attacks on dancing, supported by wildly out-of-context quotations from Church Fathers or Jansenist-influenced Frenchmen,5 in order to conclude than any and all dancing is evil, even sinful. Nothing could be more absurd, provided we are talking about graceful dances conducted among morally upright people.

And that is the first problem. When St. John Chrysostom condemns dancing, he’s not talking about something like the Virginia Reel or an English country dance. He’s talking about the lascivious, frenzied, shameless dancing of unbelievers, often enough connected to pagan cults or done in honor of pagan “gods.” He’s warning Christians against carrying these bad habits with them into their own gatherings. It’s very sound advice; it’s the same advice I give to young people today, when I tell them to avoid the worldly activities of neo-pagans and at all costs to keep those disgraceful recreations out of the gatherings of Catholics.

If one examines carefully the famous Christian writers who are down on dancing, one will usually find their negative attitude justified by particulars of their socio-cultural context. For example, St John Mary Vianney’s strict policy against dancing makes sense when one realizes the situation in Ars at the time. Mary Reed Newland has a delicious way of putting it:

The people of Ars did not do the stately gavotte or minuet but the bourrée, a polka-like step which, fueled by hearty drinking, degenerated into a rustic bacchanale after which the couples drifted off to the hedges—and nine months later saw the inevitable results.6

But even if there are some reputable authors (reputable, that is, on most topics) who think all dancing is bad, who made them infallible authorities? I hate to break it to you, but famous writers can be wrong. We take our strict marching orders from God in His revelation and the Church in her binding decisions.

As for Scripture, we can say (at very least) that it presents dancing as both good and bad, depending on the manner and purpose of it. Here are just a few verses one might ponder before condemning dance tout court:

“Their little ones go out like a flock, and their children dance and play.” (Job 21:11)

“A time to weep, and a time to laugh. A time to mourn, and a time to dance.” (Eccles 3:4)

“I will build thee again, and thou shalt be built, O virgin of Israel: thou shalt again be adorned with thy timbrels, and shalt go forth in the dances of them that make merry…. Then shall the virgin rejoice in the dance, the young men and old men together: and I will turn their mourning into joy, and will comfort them, and make them joyful after their sorrow.” (Jer 31:4, 13)

“They are like to children sitting in the marketplace, and speaking one to another, and saying: We have piped to you, and you have not danced: we have mourned, and you have not wept.” (Lk 7:32)

“Now his elder son was in the field, and when he came and drew nigh to the house, he heard music and dancing.” (Lk 15:25) Considering that the parable of the Prodigal Son is meant to reflect the superabundant love of the Father for sinful mankind, this detail is not random.

Sharon Kabel demonstrates that the Church’s magisterium does not have an “official position on dancing,” much less that it condemns it outright.

To show that I am not making up the problem, here’s a letter I received not long ago:

N. and I have been teaching ballroom and international folk dances to the local private Catholic high school for the last several years. We have been teaching and putting on dances since 1974 (50 years). All of these events have been (in my opinion) wholesome ones. Always good music, lyrics, well-lighted, modestly dressed venues, virtually always Catholic venues. Most were fundraisers for pro-life groups, homeschooling, parishes, parish schools, and private Catholic schools, while others were often weddings of friends. I have continued to conduct these events since I could see the desire for modest dances. But my local traditional parish condemns dancing altogether. How can I reconcile this what what I have been doing — and what I have seen — for half a century?

Here’s how I replied.

The deviations that can creep into dancing are many, but they are not the ones present at the kind of events you are talking about. And by comparison with what most kids are doing, they are positively fairy-tale innocent. I would maintain that a much bigger problem in trad circles is that boys and girls don’t have many healthy and normal opportunities for interacting, so they often barely associate with one another, are afraid of the opposite sex, and get into other troubles, not the least of which is spending years of youth in loneliness or only with members of the same sex.

I have noticed it seems harder and harder for good Catholic young people to find potential spouses. There are lots of bachelors and maids who could use well-conducted dances as icebreakers and true “socials,” without the scariness or seriousness of one-on-one dates. We are doing our young people a huge disservice if we hedge their relations about with artificial prohibitions in an effort to overcompensate for the sexual revolution. Formal dancing was, is, an elegant solution for bringing young people together and helping them to get to know each other; it is also a pleasant pastime for the married.

The Church Fathers condemn pagan dancing aimed at sensual intoxication, not formal dances of the kind that Christians themselves invented throughout the Christian era! Moreover, even if line-dancing and country dancing may be superior to dancing that is limited to couples, it is wrong to take a puritanical stance toward the latter, provided there is no sensuality (e.g., as occurs with the tango).

We shall now proceed to Dorothy’s article, which the author herself graciously recorded for us.

Why Catholics Must Learn to Dance

by Dorothy Cummings McLean

Rumor has whispered in my ear that a growing number of traditionalist Catholics have turned their backs on dancing, even ballroom and country dancing, considering it immoral. They might, at best, dance with their spouse, fiancé, or the person wha’ brung him or her, but that’s it. None of this dancing with 13 different people at a Scottish ceilidh or ball, one after the other.

This astounds me, for acting as if the good old dances were immoral and well-filled dance cards evidence of promiscuity is not traditional at all. In fact, it is the insistence on dancing with only one person that our ancestors would have looked at askance. In Georgian Britain and Antebellum America, married ladies considered past dancing age would sit on the sidelines and count how many times Mr. X danced with Miss Y. If it were more than twice, they would cluck and cackle like hens, and Miss Y would never hear the end of it. Meanwhile, it would be considered an extraordinary and tasteless spectacle if Mr. Z danced with Mrs. Z all night or emerged from the card room to dance with Mrs. Z alone.

Of course, the more high-minded of our ancestors considered certain dances risqué. One is the waltz, which broke the age-old convention of dancers merely holding their partners’ hands or arms if they touched at all. In the original waltz, the gentleman encircled the lady’s waist with his arm, gathering her up in a sort of half-hug. This shocked even Lord Byron, whose antics didn’t give him the right to be shocked by anything, if you ask me.

But in the ordinary social ballroom waltz, as it is danced today, the gentleman puts his right hand on the lady’s left shoulder blade, and they keep a decorous distance. Yes, in competitive waltzing, such as we might watch on TV, dancers press their tummies together, and I can well understand traditionalist Catholics objecting to that. Indeed, there are many dances popular today that I wouldn’t dance myself, including the tango—however much Mr. and Mrs. Vernon Castle protest in their 1914 book that the tango is perfectly refined.

The Castles had their work cut out for them, for they were fighting two forces: the ridiculous and “unrefined” dances popular at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries (like the Bunny Hug and the Turkey Trot) and the American clergymen condemning dancing tout court. Thus, their Modern Dancing contains many useful arguments I can use today.

“If we bar dancing from the world, we bar one of the supreme human expressions of happiness and exultation,” the Castles observe.

Very true. Who has not longed to dance a joyous jig despite not knowing the steps?

“The attempt to start a moral campaign against all modern dancing is destructive rather than constructive unless we offer something better in its place,” they add.

Since happy human beings cannot help but move to music, we must offer something better than the bumping and grinding of nightclubs: waltzing, country dances, and swing-dancing are the “something better” I promote myself.

The Castles add: “Many prominent citizens and some of our clergy have recently denounced modern dancing…. Let us establish once and for all a standard of modern dancing which will demonstrate that these dances can be made graceful, artistic, charming and…refined.”

And they glided about in the form of the One Step known as the Castle Walk, which had become all the rage.

As we all know, King David danced before the Lord, and before that Moses’ sister Miriam took a tambourine in hand and jigged with joy after escaping bondage in Egypt. There are other references to dancing in Holy Scripture, too. The Book of Ecclesiastes informs us that there is “a time to mourn, and a time to dance” (3:4). The Book of Jeremiah contains a promise from the Lord that the “maidens shall rejoice in the dance, both young men and old together” (31:13). Psalm 149:3 exhorts us to praise God’s name in dance.

Yes, I know all these texts have been used as justification to introduce ladies in leotards to prance and shimmy in front of the altar, as if Miriam herself stripped down to a body stocking and channeled Isadora Duncan. Not only is there a “time to dance,” there is a place to dance, and that’s not the parish church. My argument is only that it’s the parish hall.

Of course, it was not unknown for Christians to dance together joyfully in churches or massive cathedrals, generally after finishing a pilgrimage. It just wasn’t part of the Most Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Here is a text from the Red Book of Montserrat (1399):

Because the pilgrims wish to sing and dance while they keep their watch at night in the church of the Blessed Mary of Montserrat, and also in the light of day; and in the church no songs should be sung unless they are chaste and pious, for that reason these songs that appear here have been written. And these should be used modestly and care taken that no one who keeps watch in prayer and contemplation is disturbed.

I am particularly fond of one tune the Montserrat pilgrims sang as they danced; it begins “We are hurrying towards death; we will sin no more.” Meanwhile, the pilgrims performed their traditional circle dances, with steps they had had to learn. They were not doing the twist or making up their own moves as they went along. In fact, those of us who were not taught to dance as children—that is, the group dances particular to our various cultures and societies—were robbed of yet another birthright.

In the interests of justice, not to mention the continuation of our cultures, we should wrest back our right to dance as our great- or great-great-grandparents danced. African Catholics who immigrate to England, for example, may be forgiven if they assume that the English lack traditional dances of their own. The contemporary English mind seems to find Morris dancing and maypoles the stuff of jokes, but there are any number of English country dances that Jane Austen certainly knew and that aficionados—in the USA and Canada, as I know firsthand—continue.

I mention England because so much of English culture is taken for granted, and is therefore invisible, or smothered under foreign imports like fish and chips. If it weren’t for cricket and a sporting/social calendar involving horses, tennis, and royalty, I would be hard-pressed to list distinctively “English” things off the top of my head after Plowman’s Lunch, cucumber sandwiches, and four o’clock tea.

Scotland, thank heavens, still has a very distinct culture shining brightly under the dross of mass-marketed modernity. An important part of that culture—even today, even despite the suicidal impulses of western nations—is Scottish country dancing, which is still taught to children in Scottish primary schools. Even semi-feral local youngsters, off their faces on booze at the racetrack, can conjure up the figures of various ceilidh dances in the mud-floored music tent, and good for them.

Naturally, this is Scottish country dancing at its lowest form, but it is still a thread in the fabric of Scottish culture connected to the World War 2 POWs imprisoned in Laufen Castle, where they worked out the Reel of the 51st Division, and to other dancing Scottish soldiers before and after, and to the formal balls and assemblies of 18th and 19th century Edinburgh, as well as to Highland barns and crofts—and westward ho to Nova Scotia and even unto Toronto, where my third-generation Scottish-Canadian mother danced the Gay Gordon with her parents at Hogmanay.

Dancing can and should be done in families—and dances should be the kind that you wouldn’t blush to do before your own. Although the snake-like women I saw wriggling an oversexed version of the bachata in a local club would probably draw the line at performing it with their fathers and brothers, no reasonable person could object to a girl waltzing with her father or brother, let alone joining him in the Dashing White Sergeant or St. Bernard’s Waltz. One of the great joys of formal dances I organize is the presence of families, sons and brothers gallantly escorting mothers and sisters to the floor. As families are the building blocks of society, families that dance continue societies that dance. Dancing is a fun, healthy activity that creates happy memories within families, and therefore also in the societies threatened with becoming ever less like families.

(And by the way: ballroom dancing is one of the only activities that combine physical health with staving off dementia, as this study in the New England Journal of Medicine shows; and the impressive catalogue of ballroom dancing’s benefits can be read here.)

Really, the only real challenge I can see to traditional social dancing is launched not by morality, let alone religion, but by embarrassment at not knowing how to dance. However, dancing is just a more advanced form of walking. Having learned to walk—and to climb—and to ride a bicycle—and perhaps even to ski or skate—you can learn how to dance. Like riding a bike, it just takes lessons and repetition. It’s up to enthusiasts like me to find teachers to provide lessons to their communities, and it’s up to would-be dancers to practice.

(Dorothy Cummings McLean lives outside Edinburgh, Scotland. She is a senior editor for LifeSiteNews. You can read other thoughts of hers, including on dancing, at her blogs Apples and Roses and Mrs. McLean’s Waltzing Party.)

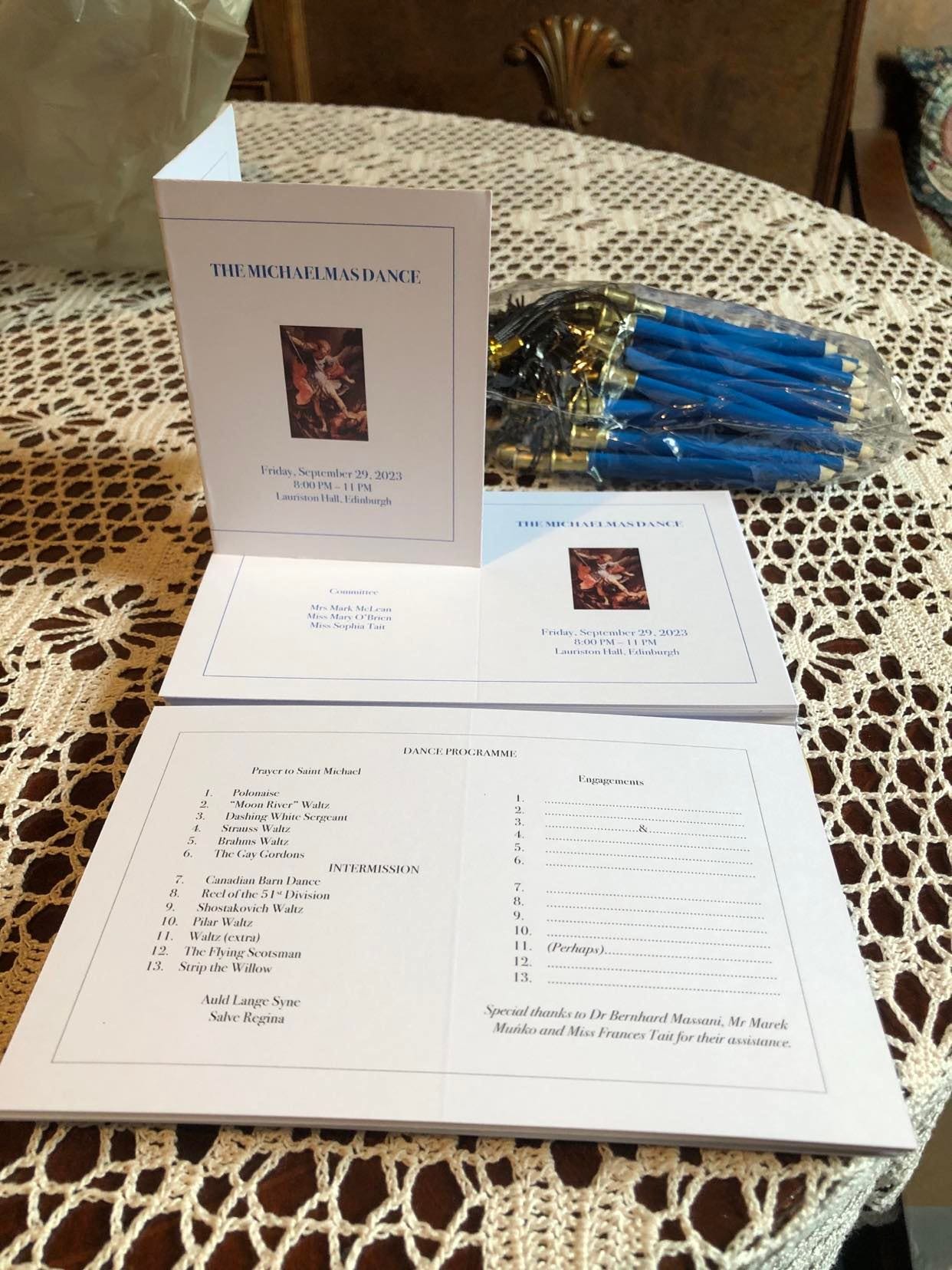

Dorothy helps coordinate events like the following, which, in my opinion, every traditional Catholic community should be emulating:

The Edinburgh Michaelmas Dance is a celebration in honour of St. Michael for Catholics who love the Traditional Latin Mass and those who like them. This year it will take place on Saturday, September 28, 2024 at 7:30 PM at the Dean Hall. Live music only: waltz, ceilidh, and swing. Black tie optional—which means wear a dinner jacket or Highland dress if you have it, but whatever is most formal in your closet if you don’t. Refreshments and parking provided. Tickets £20 for adults, £15 for teens accompanied by a parent or parents. To purchase tickets and more information, contact Dorothy McLean at dorfle@yahoo.ca

A Normal Village Experience

by Julian Kwasniewski7

I can second the thoughts shared above when it comes to a strange suspicion of dancing in traditionalist circles. It seems that it often stems from a lack of recognition that just because anyone can make a good or neutral action into an occasion of sin means both that they will, and that that good or neutral action should therefore be forbidden to all!

Sharon Kabel’s “Fact Check” quotes a pamphlet which sums up the rad-trad take on dancing as sinful. It’s worth quoting here, and responding to each line (I have added the numbers to make it easy to identify each of the points I want to address):

Now, what is the moral issue here? (1) The moral problem is unmarried young men and women dancing together in bodily contact, though the Vatican decree did not even make this distinction. (2) Married couples dancing with their own spouses is not a moral issue, but the unmarried morally cannot have a part in dances that have bodily contact. Most sins begin with an image in the imagination — bad thoughts — have you ever had a bad thought that was hard to push away? (3) When there is also a physical image before the eyes, sin is even more likely. And when one can touch and handle that physical image, sin is very likely. (4) This is what happens in dancing.

If you want to know where this train of thought leads, look to Islam:

This is not the normal village experience in Christendom. The “normal village experience” — which is what I’m striving for in my corner of the world — looks a lot more like Pieter Brueghel’s “Village Dance”:

Be that as it may, the paragraph above reveals a significant case of psychological inflexibility and a view of the Church’s moral teaching unnecessarily colored and caricatured by a moralistic OCD compulsion.

To respond to each of these main points:

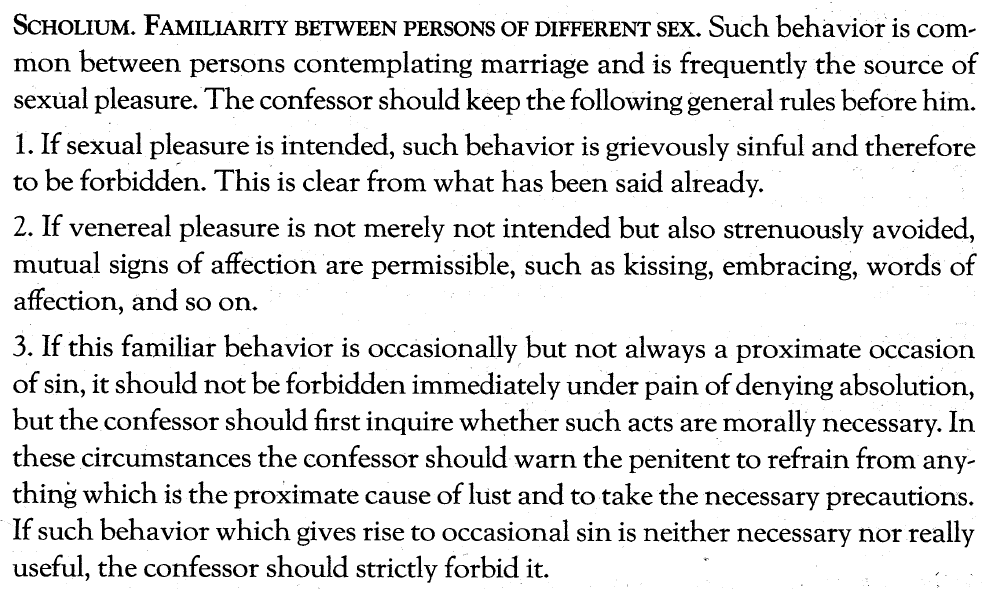

(1) “The moral problem is unmarried young men and women dancing together in bodily contact.” This implies that unmarried men and women should never touch each other. I’d like to see someone argue that, but if they did, how could courtship ever include hand-holding, hugging, and kissing of any sort — on the hand, cheek, or lips (I’d be prepared to argue that it is permissible for engaged couples to kiss on the lips; but that is another topic). It’s helpful to look at the question of physical affection between unmarried people as treated in Prummer’s Handbook of Moral Theology. First published in 1921, and reprinted more recently, this is an international classic in moral theology. Look at his clear and reasonable take on physical affection between those contemplating marriage (no. 517, pg. 220):

First of all, the sort of familiarity Prummer describes clearly extends to traditional dancing. And it is also true that, generally, all young men and women are “persons contemplating marriage.” Young men: If you are not dating or courting, you won’t want to kiss or embrace your partner, but in order to eventually get a partner, you need to talk to young ladies! You have to learn how to be comfortable, courteous, and charming! How to socialize without awkwardness and be a true gentleman—a man who is gentle, and that means both attractive in a masculine way (able to dress up and comb your hair), able to give marks of courtesy with restraint (opening doors, etc.), and full of a gentle social strength that makes women comfortable and happy to be around you. If you give the impression of either lusting after them or having a panic attack from saying “hello,” good luck finding a wife—or even a friend.

It seems to me that the sort of dancing we are speaking of is in fact a special case of controlled touch that makes young men and women better able to relate with grace towards each other. The structure involves several helpful aspects:

Most dances last 2-5 minutes: there is a definite and short amount of time you are close to your partner, and so time is an important factor in the healthy structure.

Choreography is another one. One is not just randomly touching one’s partner: specific moves require attention and coordination, and are impossible to execute if one is trying to cuddle.

Group setting is another structured aspect: one is not alone behind the barn, and in line dances one often switches partners. This puts you in a setting where you will naturally want to behave, not just to impress your partner but to impress everyone, both men and women, with your decorous skill.

(2) “Married couples dancing with their own spouses is not a moral issue.” This seems to suggest that married couples could dance as lasciviously as they liked, which strikes me as odd. Obviously there are plenty of ways of being affectionate that are permissible and good between married couples that decency and propriety forbid on the dancefloor. If married couples started dancing like they were in the privacy of their bedroom, nobody would feel comfortable even if they could consult their little moral notebook and check the box that says “no moral issue.” Actually, there would be a moral issue, because such behavior would be totally out of place, and that, in and of itself, is a bad example and possible scandal. So this whole distinction seems artificial and forced.

(3) “When there is also a physical image before the eyes, sin is even more likely. And when one can touch and handle that physical image, sin is very likely.” This is true, but only in certain circumstances: out of context and in this particular application, it is, at best, a pitiful half-truth. The author fails even to consider the fact that a young man tempted to lust in his imagination might find that interacting with a real woman outside of his imagination might actually help alleviate intrusive lustful thoughts by making the personhood of his opposite-sex interlocutor more real to him.

The state of mind represented here, in this woefully bad advice, is the exact opposite of the good advice young men are given when they are told that if they struggle with lustful attraction to their female peers, they need to “look them in the eyes.” The point, in other words, is to interact personally with fellow female persons rather than objectifying them. I can think of no approach more objectifying than to say that one should not look at or lightly hold a girl’s hand in a dance…because then you might objectify her! The whole point of the social interaction is to not objectify, and rather treat the partner as what she truly is: a person to be looked at and occasionally touched (since you both exist in a physical world), not an object of fear to be avoided (or worse, merely used when use becomes permissible; note the subterranean connection with point 2 above).

If this rad-trad objection were correct, a man should never even look at a woman — nor hold her hand, give her a hug, lend her his arm, help her put on a coat, or prevent her from falling off a cliff by throwing his arm around her waist. On this logic, men and women should not only sit on opposite sides of the church, they might even be advised to go to segregated services. Heck, maybe women should not be allowed out of the house at all — not without a burka, at any rate!

(4) “This is what happens in dancing.” Anyone who has tried to dance a traditional dance will simply know that there is so much going on that this is not at all an accurate representation of the dancer’s state of mind. It is a gross oversimplification, done with a moral arithmetic untethered from reality. When I’m dancing, I’m usually thinking so much about getting the steps right, and keeping to the music, that I don’t have much time to think of anything else! And a structured dance requiring some technical skill—such as the Virginia Reel, or even waltzing properly—requires a lot of attention. In reality, traditional dancing, even waltzes, are more like physical exercise than they are like intimate affection.

I often wonder if the people who oppose dancing have ever actually danced!

And to that point, while Dorothy mentions competitive waltzing as a bit “cuddly,” I should point out that there are several types of waltzing. In traditional waltzing one finds that the “frame” of the couple has to be rather stiff; at least in certain styles of waltzing, you cannot “close” your frame by bringing your shoulders together, putting your arm around her waist, and cuddling up to your partner. Look at this video. For the gentleman to lead, he needs to be rather stiff, holding the woman a foot or so away from him. No need to do every dip or close move; this is the tippity-top of high-end waltzing. I would be proud of the culture of any parish possessed of young adults capable of dancing like this:

Here’s a scene from the famous BBC adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, showing how one of the many dances of that period was done. This sort of thing isn’t hard to learn today, nor could there be any possible objection to it (prescinding from the withering dialogue):

And finally, let’s get a good glimpse of the Virginia Reel. I can think of few things that would better socially acculturate our awkward, lonely, and depressed teenagers. This is a normal village experience… not being told dancing is evil.

Thanks be to God that many traditional lay Catholics have the common sense, life experience, social awareness, and cultural literacy to be able to see that something is deeply wrong with arguments against well-regulated social dancing, and that, on the contrary, it is a healthy recreation with many virtues and benefits, the presence of which needs to grow considerably in our communities.

Late at night, unfortunately, DJs of bad taste tended to take over and started playing their favorite rock and pop songs. I never understood why a college that officially frowned upon such music never lifted a finger to prevent this abuse. I always left before that point, as I wanted to leave with pleasant memories. Nevertheless, this deviation is accidental to the question we are discussing, which is whether formal dancing is good.

Though I do wish all these schools would hold formal balls; maybe they do and I just haven’t heard about it.

With some caveats, again, about the bad taste in music that would creep in, unmonitored and unregulated by staff, as the evening went on.

In my opinion, he is right, although trying to convince young adults of this fact is even more difficult than trying to convince them to eat well, dress well, and get adequate sleep.

The Jansenist influence is real. Msgr. Ronald Knox, in his masterpiece Enthusiasm (Oxford, 1950) argues that the Jansenists developed asceticism into “Puritanism” by maintaining that everything sensibly pleasant is sinful or suspect. He notes: “Disapproval of dancing…or of the theatre was a mark of Jansenism long after Jansenism had ceased to be a genuine religious inspiration. And such disapproval is so far removed from our present Catholic attitude that we are tempted to ask whether, here, Port Royal had not been taking lessons from Geneva [i.e., from Calvinism]…. What Jansenism did was to exaggerate this protest [against Humanism]; out of all proportion, most of us will think, and rendering a disservice to Christendom. A Counter-renaissance was needed, but no so violent a swing in the other direction” (pp. 211-12).

The Saint Book (Seabury Press, 1979), 126.

A modified version of this article appeared at Crisis Magazine this past Monday under the title “Go Forth in Dance.”

A GENERAL COMMENT ABOUT THE COMMENTS

It is almost a cause of despair to see how poorly people read nowadays. Perhaps the naysayers here simply did not attend carefully enough to the original articles.

1. We made it absolutely clear that we exclude many forms of dancing, either because they are formless, graceless, and crass (freeform 'dancing' in nightclubs, etc.), or because they are too sensual (tango, slow dancing where a couple is pressed up against each other). Likewise I made it clear that I am referring to formal social ballroom dancing and country dancing or contra dancing. In fact, I even admitted a preference for group dances over couple dances.

2. I also made it sufficiently clear that I am praising dances that are well-regulated as to the music and types of dances chosen, and that do involve a certain level of chaperoning. The kids are not being thrown into each other's arms for necking. Good heavens, has any of the objectors here actually BEEN to the kind of dance I'm describing - the kind shown in the pictures? Have they danced an English country dance, or a Virginial Reel, or learned the waltz (as it is typically done nowadays, which is not a body-to-body hug), or the swing? I highly doubt it, because if they had, they would see how quickly their arguments melt away.

3. Julian's article argued directly against the claim that any contact between unmarried persons of opposite sexes is a near occasion of sin and therefore immoral -- a position that absolutely cannot be defended in moral theology. This position leads to absurdities and therefore is not compatible with Catholicism that prizes faith and reason.

4. The situation of our young people in 2024 is much different, and much worse, than it was in earlier times. They do not have many healthy opportunities for morally upright in-person mingling, as modernity has atomized and fragmented our societies (our "villages," as it were). They are stuck on the internet, working jobs with long hours, and maybe, if they are lucky, seeing their friends at a Sunday TLM. The argument here very much depends on seeing that dancing has a social context and that such contexts can and do change over time. Applying like a simplistic template what St John Chrysostom said in the fourth century or what St John Vianney said in Ars (see Mary Reed Newland description above) to a social ballroom dance in 2024 is a glaring violation of how moral argumentation should be made.

5. Finally, if someone is inflamed with lust by the mere sight, let alone arm's-length touch, of a lady, or by the holding of her hand as part of a group dance, then I believe he should schedule an appointment with a psychiatrist, as he has a lot of work to do to heal a diseased psyche. If there is someone who finds even a well-regulated dance an occasion of sin, he should not attend it; but that says more about him than it does about dancing as a healthy recreation.

A post defending dancing with a clip from Pride and Prejudice—simply amazing. Thank you, all three of you, for this wonderful piece!