Why the Epistle Should Be Read Eastwards and the Gospel Northwards (Part 2: Conclusion)

Responding to Brant Pitre’s Critique of the Tridentine Rite

Special Christmas “BOGO” Offer

Anyone who takes out a paid subscription to Tradition & Sanity will receive a free one-year (paid) subscription to Robert Keim’s Via Mediaevalis, which I consider one of the top Catholic Substacks out there, and with which I am honored to be partnering. Offer valid until tomorrow (Friday, December 20th):

Those who would like to lend their support to Tradition & Sanity in other ways will find options at the end of this post. Now on to the day’s article!

Throwing a deliberate curveball

In the first part, we laid the groundwork for understanding why the classical Roman Rite reads the Epistle to the east. It is not because the pope in his private chapel happened to do it this way, since there was no reason to bother to turn around. No, this custom of reading toward the east was widespread in many local uses and seems to have developed organically when the ambos of ancient Christian architecture were no longer utilized.1 My hypothesis is that the readings, like everything else in the rite, were gravitationally drawn toward the act of divine worship, so that even externally they were brought into conformity with the orientation of the sacrifice.

We came to an abrupt conclusion with a conundrum: If the eastward stance is well suited to the worship of God and the expectation of Christ, why would the liturgy turn the deacon toward the north wall for the proclamation of the Gospel?

Here, dear friends, is where the liturgy surprises us by heading in a new direction. But it makes perfect sense if we stop to think about it.

If the Gospel is the verbal presence of Christ par excellence and the priest or deacon proclaiming it is, at that moment, acting in persona Christi, then it would not make sense for the reader of the Gospel to face ad orientem, toward Christ the Orient. That would be like saying Christ is talking to Himself. Rather, the Gospel is Christ addressing the world. And I mean that very specifically: the world, that is, the nations, the gentiles, the whole of creation, to which the Gospel must be preached so that it may be converted, blessed, sanctified, and saved.

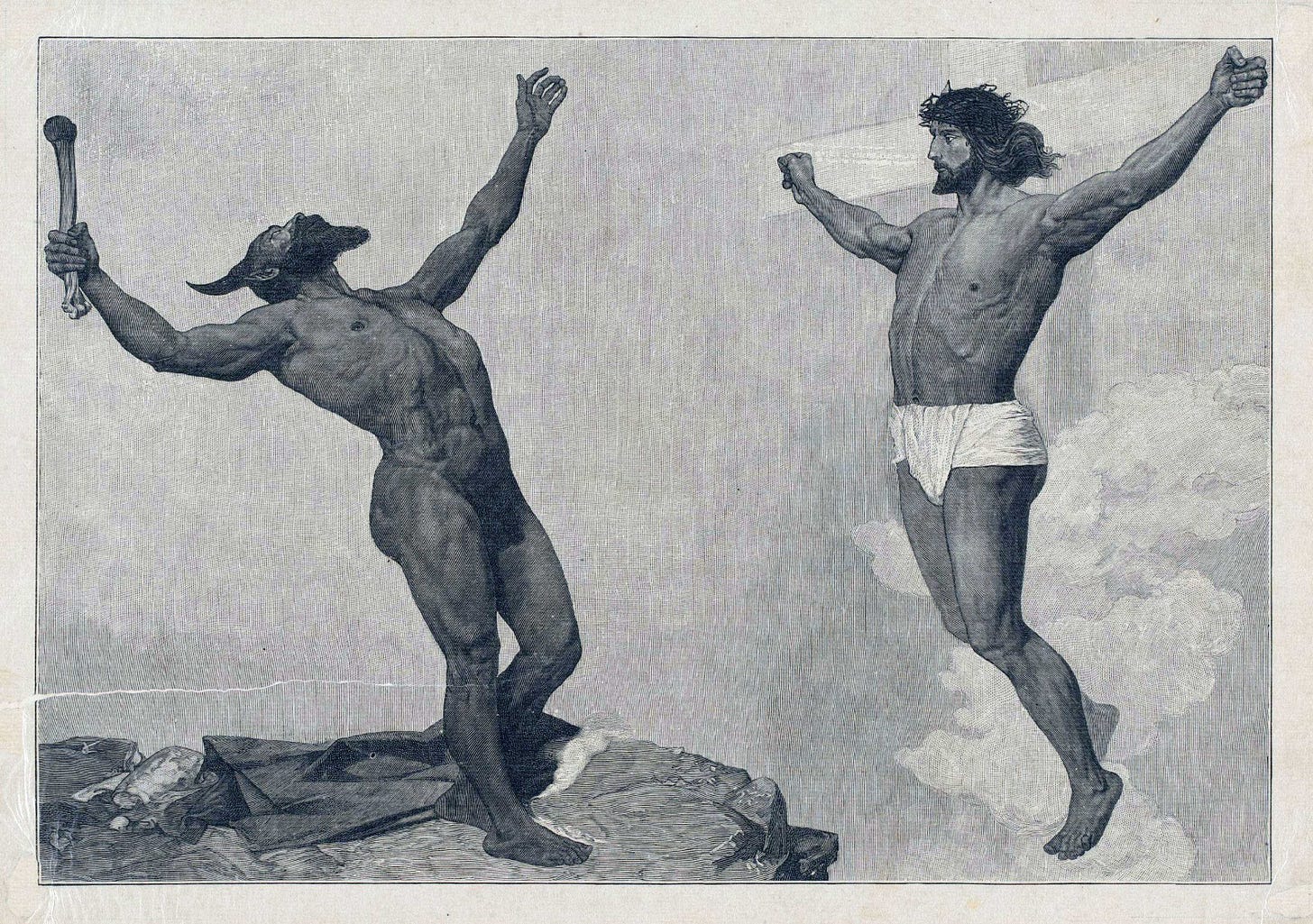

Therefore, in the historical development of the Roman rite, the Gospel came to be sung facing north because north was the symbol of the unconverted heathen world that needed to be evangelized. The north, one might say, represents the world at its most godless, sunk in the bad news of original sin and ever-compounding human evil.2 It is the world without the good news, waiting, yearning for the Gospel, yet also opposed to it.

This explains the almost Roman military formation of the candlebearers, thurifer, subdeacon, and deacon: they are marching to the northern extremity of the church, as if to set up a fortress on the border of the enemy. The Gospel is a light for exposing and defeating the evil that has overtaken God’s good creation. “By a long tradition, the north represents the dark realm where the light of the gospel has not yet shone. We read the Gospel toward the north to represent the Church’s mission to the unevangelized.”3

Why does the north represent the unconverted world?

Now, every symbol has a concrete foundation either in nature or in culture. Symbols are not arbitrary. But it might seem like this symbol, the north as the unconverted pagan world, is arbitrary. What’s so bad about the north? Why are we picking on it? Isn’t it offensive to Canadians, Russians, and Norwegians?

In all seriousness, there are profound reasons for this connection between the north and evil. I think no one who enjoys the sunshine and warmth of Florida or Arizona will disagree with me that there is something grim and inhospitable about northern climes, wrapped in months of darkness and trapped in subzero temperatures where life can barely hang on. It is not for nothing that Dante portrays Satan, in the lowest circle of hell, frozen into the lake of ice, and along with him, all traitors in whose hearts no love burns. Nor is it surprising that J.R.R. Tolkien in The Silmarillion places the residence of the most evil character in his legendarium, Morgoth, in the far north; one of Morgoth’s many titles is “the Dark Power of the North.”

Dante and Tolkien, however, simply take their cue from Sacred Scripture. Old Testament texts particularly connect the north with evil — either the pagan empires of Israel’s great enemies Assyria and Babylon, or adulterous covenant-breaking Israel itself (which is to the north of Jerusalem). The prophets Jeremiah and Isaiah have a lot to say about it. Jeremiah 1:14: “From the north shall an evil break forth upon all the inhabitants of the land, for behold, I will call together all the families of the kingdoms of the north.” Jeremiah 6:1: “Evil is seen out of the north, and a great destruction.”

As if drafting a liturgical rubric, Jeremiah 3:12 comes right out and says: “Go, and proclaim these words toward the north, and thou shalt say: Return, O rebellious Israel, saith the Lord, and I will not turn away my face from you: for I am holy, saith the Lord, and I will not be angry for ever.” Jeremiah 31:8–9 strikes a hopeful note, saying that God will bring from “the north country…the blind, and the lame, the woman with child, and she that is bringing forth,” and will lead them “in mercy…through torrents of waters” (i.e., through baptism).

For his part, the prophet Isaiah puts in the mouth of Babylon, a potent symbol of evil, these words: “I will sit on the mount of assembly in the far north” (14:13–14; cf. 41:25).4 So strong was the equation of “north” with “evil” that, after the Council of Trent, churches were allowed to be built, with episcopal permission, in any direction except toward the north.5

But could there be deeper reasons for the Bible’s general aversion to the north? In his fascinating essay “The Ancient Cosmological Roots of Facing North for the Gospel,” Scripture scholar Dr. Jeremy Holmes anwers in the affirmative. His argument can be summarized thus. The ancients did not know about magnetic north; they found north by looking to the heavens, where the constellations rotate around the north star.

As the sun’s rising is the overwhelming fact of day, the north star’s constant and central presence is the obvious fact of night, second to the moon in brilliance but second to none in reliability. But what in fact is the north star?

Thanks to the wobbling of the earth’s rotation, called “precession,”

over the course of about 26,000 years, a line drawn through the earth’s axis describes a complete circle in the sky, and along the way, various stars become the “north star,” i.e., the star currently aligned with the earth’s axis. Today, the north star is Polaris, but as recently as 4,000 years ago the north star was Thuban, located in an entirely different constellation. Egyptian temples were specially built so that Thuban would be visible through a door on one particular side. If you go out at night and find Thuban in the sky, you are looking at the north star as Abraham would have known it when God called him in about 2000 BC.

Holmes points out that all the familiar constellations in the night sky, which not even the Greeks invented but only received, are arranged around Thuban in such a way that the civilization that first named them must have been the Sumerians and the Babylonians. But what is Thuban? It’s an Arabic word for the constellation of which it is a part: Draco.

For the ancient Babylonians (our closest witnesses to the original Sumerian tradition), the constellation Draco was Tiamat, the sea. As the story goes, Tiamat was the mother of all the gods, but then turned on the gods in the form of a serpent and attempted to eat them all…. For the ancient Greeks, Draco had a parallel role. As Tiamat turned on Marduk and company, so the Greeks told of the time the Titans attempted to overthrow the gods of Olympus. At one point in the battle, a dragon attacked Athena, but she slew it and threw it up into the sky where it wrapped around the earth’s axis to form the constellation we see today.

If you turn your mind to the Book of Revelation, chapter 12, you will recall the woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars. The great dragon tried to devour her child; this ancient serpent is Satan. The text of Isaiah therefore with precision connects Satan with the northern stars.

Holmes again:

Given the trail of evidence I have laid out associating Satan with the north and with stars and with the dragon of ancient mythology, I don’t think it too much of a leap to see Satan as represented by the constellation Draco.

To sum up the whole argument:

For the ancient Sumerians, “north” meant toward the dragon, who ruled the sky when all was dark, but around the time when God called Abraham out of Sumeria, Thuban lost his place as the center of the night sky. This dragon was understood as the foe of the gods, and in Scripture was eventually seen as the foe of God — Satan, that ancient serpent. The reign of the dragon has been overthrown by the resurrection of Christ, the rising sun.

It makes all the sense in the world that we would face the rising sun when we worship. It makes all the sense in the world that we would not face north, toward Draco, when we worship. And although it might surprise our human instincts, it makes perfect sense in God’s infinite mercy that we would proclaim the Gospel to the north, to all those under Satan’s dominion.

From the cosmic to the civic dimension

We have now discussed geographical or climatic, biblical, and historical/cosmological reasons for the Gospel to be proclaimed to the north.6 We can add a bit of “local color” to complete the picture. After the center of Christianity shifted from Jerusalem to Rome (as the Acts of the Apostles already foreshadows), the biblical associations would have been amplified by the map of the world as it appeared to the ancient Romans.

From the end of the first century until the beginning of the fifth century and even later, the Romans built and maintained thousands of miles of limites or fortified defenses along the frontier of the empire. Among the most famous of these was the limes Germanicus, stretching from the North Sea outlet of the Rhine down to Regensburg on the Danube. North of the limes there were vast regions of “barbarians,” people regarded as having no culture and no orderly religion, but wild Germanic tribes with strange deities and beliefs. They were the enemies of imperial Rome, but they were also the gentiles whom the successors of the apostles were sent to evangelize; and, as a matter of fact, it was the barbarian peoples, baptized and civilized, who became the lifeblood of medieval Christendom. Just as the Roman Canon, written in the hot Mediterranean, envisions heaven as a place of coolness (locum refrigerii), so too the rubrics of the Mass reflect a habit of thinking about the north that connects it with dangerous barbarians yet to be claimed for Jesus Christ.

These are only a few of the many examples of how the words and rubrics of the Mass reflect the confluence of ancient Hebrew, Greek, and Roman civilizations. Just as our theology has a triple root — Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome — so too does our liturgy, though perhaps in that case it would be better to say Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Rome.

What we are supposed to learn from the directions

At this point, a pretty obvious objection could be raised. In Part 1, I argued that the reason the Epistle is read toward the east is that it is not simply didactic, offered to us, but also latreutic, that is, an act of worship offered to God, and that it is important to place the vertical or transcendent aspect over the horizontal or immanent aspect. Yet just now I have been explaining that we read the Gospel to the north to symbolize the preaching of the good news to unbelievers, which might seem very much a this-worldly and people-oriented perspective, not a mode of glorifying God by the recitation of His own works and wonders.

Stated as such, it sounds like a dilemma; but I think it’s a false dilemma.

The northward stance is a symbol of the proclamation of the truth to the pagans — since presumably there are not any actual pagans gathered in the north side of the church. (It often happens at a conference or other large gathering that several bishops will be standing in choir on the north side, but I highly doubt that any subliminal message is intended.)7 What this stance is meant to show is the power of the Word to convert human hearts from unbelief to faith. This is a manner of glorifying God for the power of His word, and so it fits into the latreutic function of the reading.

The emphasis, in other words, is not on instruction per se but on confrontation, conviction, conversion, and christianization. Obviously, the Word has to be received in order for its power to be felt and manifested; but the power is in the Word and glorifies the Father from whom it comes and the Spirit by whom it pieces hearts. The emphasis is on the heat that melts the ice, the light that banishes the darkness, the truth that triumphs over ignorance, error, and deceit. In that way, the northward utterance of the Gospel is just as theocentric as the eastward utterance of the Epistle.

Some allegorical commentaries on the Mass maintain that the Epistle is directed to those who already believe — those who are within the household of the faith — while the Gospel is directed, as it were, to the unbelievers. Each reading demonstrates a different facet of revelation: its ad intra or internal function of strengthening the members of the body gathered within, and its ad extra or evangelistic function of adding new members to the body from without.

Whatever we make of such allegorical claims, we can rest assured that both the Epistle and the Gospel have an application to each one of us, regardless of how briefly or how long we have been a Catholic. For, as Cardinal Charles Journet writes:

The Church contains the just; but precisely in so far as they are just. To the extent to which, beside the profound choice of the will that unites them to God, they still harbour a region of shadows, a concession to venial sin, to that extent they are partially outside the Church. Two categories of members alone are wholly within her — the newly baptized who have not yet sinned, and those souls that are consummated in sanctity, all absorbed by the light, like those of whom St. John of the Cross writes, in the last strophe of his Canticle, that henceforth they are no more troubled by the assaults of the devil or by the revolts of the passions…. Thus the frontier of the Church passes through each one of those who call themselves her members, enclosing within her bounds all that is pure and holy, leaving outside all that is sin and stain.8

As Journet says, the vast majority of us are still divided between the part of us that is Christianized and the part that is still somewhat pagan. There are areas of our lives full of light, and others that are in shadow. In some ways, we take the blazing sun as our point of orientation, but in other ways we are inclined to hide in the dark and take our bearings from Draco. The military frontier that divides the believer from the unbeliever runs straight through the map of our soul.

When the Epistle is read to the east, we sit facing in the same direction, as a kind of dry run for the Holy Sacrifice soon to come, when we will kneel and the priest will offer the pure, holy, spotless Victim in our name and for our sakes. When the Gospel is read to the north, we stand, in reverence to Christ, and we are reminded by the very oddness of the direction that this Gospel is not “ours” like a familiar possession we can stick in our pocket, something we’ve mastered or could outgrow, but comes always to us from the outside, to convert us, to penetrate those regions of the soul that are still unconverted.

There is one last point worth mentioning.

Escaping the closed circle

Cardinal Ratzinger famously pointed out that the versus populum arrangement of the Novus Ordo turns the community into a “self-enclosed circle,” characterized by self-referentiality.

The so-called Liturgy of the Word is especially vulnerable to these faults, because it typically consists of a series of individuals, mostly emerging unvested from the church’s nave rather than from the sanctuary, who all stand at the same spot, the so-called ambo, facing the congregation, and read out a long series of texts, from announcements to several readings to the homily to the general intercessions, in a monotonous sequence that contains no differentiation of place, direction, hierarchy, or melody. The dominant impression is that of drowning in a lake of verbiage into which everyone has been forcibly plunged.9 This entire portion of the Mass is focused on the congregation right in front of the ambo, and in this way becomes a self-enclosed circle that is not aimed outside itself.

The traditional Mass of the Catechumens, on the other hand, is both fascinating to behold, because there is a sacred symbolic choreography at work, and a simultaneous peripheralizing of the congregation, since none of the ceremony is directed at the people; it isn’t even in their language. The old Mass opens up a large psychological space between the conduct of the liturgy and the faithful present, so that the faithful have to cross a spiritual landscape to arrive at their destination. The result can be good or bad. It will be good if we make an effort to cross that interior terrain; it will be bad if we are passive and expect to be spoon-fed. But what is crucial is that the liturgy has (if I can use this phrase) an “open” architecture, not limited to the congregation on hand, not limited to one level or type of learning, not hiding or falsifying the mystery of the Church that exceeds every place and time.

Michael Fiedrowicz puts it like this: “The practice of directing the proclamation of the Gospel toward the north is a sign of the universal opening of the Church that does not limit the glad tidings to its own community.” The good news is directed always beyond us, but not excluding us; the word travels (so to speak) in a line that does not end in our circle, as a radius to the center, but rather touches the circle tangentially, at a perpendicular angle to the radius.10

Fiedrowicz cites Guillard, who writes:

The orientation of these readings is a sign of openness to the universality of the Church and not of retreat to the listening community.11

Another way of putting this is that the faithful are not in the position of subjects to whom the readings belong, but objects against whom the readings resound; the word is something that, no matter how much or how well received it is, remains ever-greater. It possesses without being possessed.

The traditional Mass has a remarkable power of communicating theological truths to all who assist at it attentively. The faithful may not be able to put into words what they are learning, but they are indeed learning, as by osmosis, a whole “curriculum” of spiritual priorities and insights. As profound as the liturgy’s symbolic language is, it remains rooted in the cosmos and in the makeup of human nature; it requires relatively little catechesis in Bible history to make the major connections. Because the Latin Mass is blessedly consistent from day to day, year to year, it’s easy to observe and notice things about it, ponder them, and achieve breakthrough moments. Because of its solidity of truth and clarity of presentation, it can speak to all — to men, women, and children, to illiterate peasants as well as monks and scholars. The tradition grew into its mature form over so many centuries for good reasons, and these reasons have a way of impressing themselves on us if we only allow the liturgy to do its quiet work of forming our souls.

Symbolism of west and south

There are two last points to take up. First, on the basis of what we’ve already covered, can we say anything about the symbolism of the west and the south?

Yes, we can. Since we know that the East always symbolizes Christ and the Second Coming, the west in liturgical history ends up symbolizing the devil and his rebellion. In ancient baptismal rites, this was played out dramatically:

The catechumen standing with his face to the west, which symbolized the abode of darkness, and stretching out his hand, or sometimes spitting out in defiance and abhorrence of the devil, was wont to make this abjuration [of Satan]. It was also customary after this for the candidate for baptism to make an explicit promise of obedience to Christ. This was called by the Greeks syntassesthai Christo, the giving of oneself over to the control of Christ…. During this declaration of attachment to Jesus Christ the person to be baptized turned towards the East as towards the region of light.12

What the Catholic Encyclopedia describes continues to be practiced in the Byzantine tradition even today, where the one to be baptized (or, if a child, his sponsor) faces west and renounces Satan three times, spits at him, then turns to the east and confesses three times that he unites himself to Christ, and then announces three times that he has united himself to Christ.13

While the Western Church has not developed this symbolism quite as much as the Eastern Church has done, we can see parallels to it in our traditional baptismal rite, where the child to be baptized proceeds from the outer door (west) to the east, and where at a certain point the priest turns around from west to east, to admit the child to the font of regeneration. This much is certain: it would be very strange for us to make a liturgical ceremony other than the repudiation of the devil take place deliberately facing westward, with our backs to the east.14

That the south represents the Church and the faithful follows from the cultural associations mentioned earlier. The faithless kingdom of Israel stood to the north; the somewhat less faithless kingdom of Judah, with its capital city of Jerusalem, was to the south. The Catholic Church was planted in the south as the ancients conceived it (the Mediterranean basin), and the barbarians lived to the north. The south is the direction where the sun is at its highest during the day, with the particularity, when using a sundial, that no shadows are cast on the ground at this time — a symbol of light winning the fight over darkness, of St Michael killing the dragon.

It seems hardly accidental that

the priest receives incense and is himself incensed during Mass from or at the south side of the altar;15

that the Epistle, with its ad intra character as instruction for the faithful community, is read or sung on the south side by the priest, or sung on the south side by the subdeacon; and

that the priest washes his hands inter innocentes again at the south side.

Moreover,

The priest, deacon, and subdeacon sit together on the south side of the chancel: it is their “base camp” where they rest and meditate.

At the third Confiteor, the priest directs his blessing toward the south, which also happens to be his right-hand side, while his left hand rests upon the altar.

Gauthier Pierozak comments:

The three compass point other than north are associated with the daily phases of the sun: East for the rising sun, south for the sun at its highest in the middle of the day, and west for the setting sun. It is worth mentioning that similarly, the daily rising sun can be associated to the annual cycle, and the winter solstice corresponding to when the duration of a solar day is the shortest. The winter solstice, which symbolizes the rebirth of the sun, the light winning the fight against darkness, happens to be at around Christmas, the birth of Jesus. In opposition, the west symbolizes the setting sun, and the entrance to darkness. Darkness can mean ignorance, blindness to faith, sin, evil, etc. It is also symbolized by the summer solstice. It is to be noticed that in the Catholic calendar, the summer solstice corresponds to the Feast of St John the Baptist (6/24). This is because the Gospel of Luke states that John was born about six months before Jesus (Luke 1:26): hence the meaning of “He must increase, I must decrease” (John 3:30).16

Art historian David Critchley pointed out to me that the mystical geography implied by the liturgy — i.e., east for Christ and the Second Coming, west for the devil rejected at baptism, north for the unbaptised, south for the Church; upward for “thine altar on high” and the heavenly liturgy, downward for those who sleep in peace beneath the flagstones — is a key to the internal iconography and arrangement of the great churches of medieval Europe.

Trust the tradition

My second and truly last point is a reminder about pastoral deviations. In some parts of the Catholic world today, especially in Europe, well-intentioned but badly misguided clergy are repeating the experiments of the preconciliar Liturgical Movement by introducing supposedly “congregation-friendly” and “active participation-promoting” practices into their Latin Masses. One of the most common of these deviations is doing the readings in the vernacular, and even doing them facing the people, as we saw at the Solemn Pontifical Mass for the Chartres pilgrimage in 2018.

Although much could be said about this (see my articles “Traditional Clergy: Please Stop Making ‘Pastoral Adaptations’” and “The Ill-Placed Charges of Purism, Elitism, and Rubricism”), here I simply wish to reiterate that the liturgical tradition has its own profound inner logic and rationale that we should respect. We ought to assume that longstanding tradition has a meaning and a message for us, one we should seek out, listen to, learn gratefully, and pass on intact. Experimentation may well be the way to find out new truths of natural science, but it is not the path to new truths about God and man; on the contrary, it leads us away from the fundamental truths that never change but can only be either remembered or forgotten, heeded or ignored, cherished or dismissed.

Let us be among those who heed and cherish the wisdom of tradition.

Consider giving Tradition & Sanity as a gift to a friend or a relative, a priest or a religious:

If you’ve already subscribed but would like to buy Julian or me a coffee to propel our writing, you can do that here:

Thank you for reading and may God bless you!

There seems to be some uncertainty and disagreement over when the use of the ambo(nes) fell out of fashion in favor of the general practice in the TLM (for practice and local custom will have varied from place to place), but the statement that this began towards the end of the first millennium seems uncontroversial. Jungmann (Mass of the Roman Rite, I, pp. 412-413) sees nothing but pointlessness in the east- and west-facing directionality of readings.

Fiedrowicz, The Traditional Mass, 89: “While the subdeacon turns toward the altar, the deacon proclaims the Gospel toward the north, in eastern-oriented churches — a symbolic expression that the Gospel should drive out the powers of darkness and convert the pagans.”

As Scripture scholar Dr. Jeremy Holmes puts it in the article mentioned just below.

Isaiah 14:13–14 was taken by the Church Fathers as a description of Lucifer’s proud attempt to seize glory by his own power: “And thou saidst in thy heart: I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God, I will sit in the mountain of the covenant, in the sides of the north. I will ascend above the height of the clouds, I will be like the most High” (Isa 14:13–14). To which, of course, the response of St. Michael was: “Who is like God?”

Fiedrowicz, The Traditional Mass, 147.

A commentator online pointed out a possible eminently practical reason: “Traditionally, solemn Mass is celebrated after terce, viz., in the morning hours. At European latitudes, where the Latin Rite took shape, the summer sun rises in the northeast, quite early in the morning. At this season, light at the hour of Terce tends to be abundant, so that a deacon proclaiming the Gospel has no need of candles to assist him. In winter, however, the affair is altered: the sun rises far south of due east, and much later, so that one’s location in the church can have a real effect on the ability to read, even with a pair of candles. To have whatever daylight there may be, directly over one’s right shoulder so that it falls upon the page, is a material practical aid. While the symbolism of proclaiming the Gospel to dark and heathen lands is meaningful and useful, one should not discount the possibility that mere practical considerations of visibility were in play as well when the rubrics were first worked out.”

It is said that in medieval times a northern window was left open during the exorcism portion of Baptism, ostensibly to allow the Devil to escape.

This text is found online. See also the same author’s Theology of the Church, 37; 212: “This opposition of light and darkness, of Christ and Belial (2 Cor 6:15), will be produced not only between Christians and their adversaries, but in the heart of each individual Christian — between what lifts him up to heaven and what drags him down to hell. … These are the same baptized men who belong at once (but partially) to two opposing cities: at times they sin, and to this extent they become involved in the city of the devil; at other times they do penance, and here they take part in the city of God.” Alexander Solzhenitsyn penned similar lines: “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart — and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained.”

For a detailed discussion of this problem, see my article Homogeneity vs. Hierarchy: On the Treatment of Verbal Moments.

See Euclid, Elements, Book III, Proposition 18.

Fiedrowicz, The Traditional Mass, 89, n36.

Catholic Encyclopedia (1907), s.v. baptismal vows. The default explanation printed in Eastern liturgical books for West-East is an excerpt from Cyril of Jerusalem’s Catechetical Homily 19.

The traditional Roman rite of the baptism of adults has a number of similarities. The priest breathes three times on the face of the candidate to drive away the unclean spirit; the candidate kneels several times and says the Lord’s prayer to signify his adherence to the Gospel, then enters the church and falls prostrate to the ground. The priest at the baptismal font first stands with his back to it until the end of the final exorcism, then turns to admit the candidate to the life-giving waters. Admittedly it’s not as “in your face” as the Byzantine, but the rite conveys the same process of escalating renunciation and attachment to Christ, symbolized by starting far from the font and moving ever closer to it.

Something like the Asperges rite, where the priest walks westward to sprinkle the faithful on one side, and then returns eastward to sprinkle the faithful on the other side, cannot be considered a violation of this point, since all the priest is doing is moving around the church to sprinkle everyone; the directionality is incidental. He is not standing to the west, reading out liturgical texts that used to be read eastward.

Though admittedly, after the Gospel, it’s from the north side, or at least from the center (the English tend to go to the center axis, the French stay where the Gospel was sung). The bishop is still incensed from the south.

Private correspondence.

"North of the limes there were vast regions of 'barbarians,' people regarded as having no culture and no orderly religion, but wild Germanic tribes with strange deities and beliefs."

The present tense would be equally fitting . . .

But in seriousness, the notion of sacred cosmology is utterly foreign to the modern mind, and thus (mostly) foreign to the liturgy it produced.

Ironic, given that modernity (as experienced in the west), with its expanded cosmos, is marked by acute anxiety concerning the ostensibly anthropocentric character of Christianity. You would predict that such anxiety would prompt a cosmological turn in liturgy, even as modernity's shrinking globe yielded sensitivity to religious variation and produced an analogous universalist turn in soteriology. But the very opposite occurred: the liturgy took an anthropological turn. Obviously, there are other salient aspects of modernity that explain this (e.g., an exaggerated humanism and psychologism, a democratical and leveling spirit, symbolic illiteracy, and so on). Still, an interesting dynamic.

This is incredibly fascinating. Thank you. Shared it with my family.